Northern Etobicoke Historical Self-Driving Tour - Part 2

HOW TO USE THIS DRIVING TOUR

- After each stop, you will find the driving instructions to the next stop. Read the driving instructions for the next stop completely before you head out as sometimes they will provide you with information about sites to look at en route.

- Don’t forget you can also the separate map of the tour route that has been provided above and available HERE on Google Maps.

- Remember that many of the sites along the way are on private property. Please respect the owners by not trespassing.

Tour Overview

This is the second of two driving tours of that part of the former City of Etobicoke that lies north of Highway 401, approximately 40% of Etobicoke’s total area. The entire area was surveyed by William Hambly in 1798, dividing it into 100 acre (40 hectare) lots that were .25 miles (.4 Km) wide and ran between north/south concession roads that were .625 miles (1 Km) apart. The first land grants were made in the very early 1800s. Initially, settlers spent most of their time clearing the land so crops could be planted and erecting at least rudimentary houses and barns, often made of logs. By the 1840s, 84% of the land in Etobicoke was owned and 50% of the owned land was under cultivation. However, by 1878, 98.8% of the land was owned and 90% of the owned land was under cultivation. By the mid to late 1800s, most log buildings would have been replaced by frame, stone or brick structures.

Northern Etobicoke had excellent soil for agriculture, and was soon specializing in wheat, dairy, livestock and fruit farming. Because the area was used almost exclusively for farming, the population was sparser than southern Etobicoke, and there were only four communities large enough to have a post office: Highfield, Smithfield, Claireville and Thistletown.

A map of Etobicoke made in the early 1940s shows that northern Etobicoke was still primarily farmland with the same four villages. But World War II changed all that, and northern Etobicoke quickly became a suburban centre that provided jobs and homes for a burgeoning post-war population.

This tour highlights the pioneer history of this area and you will see all of the sites that have survived from the 19th century. It will also cover some aspects of modern history, focusing on the time period after World War II when the area saw unprecedented growth. In addition to having large residential areas and parks, northern Etobicoke has a significant number of industrial and commercial properties, and although all but one of the farms have disappeared, a few parcels of land still remain undeveloped.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS will be found in italics and located after each stop. Read the driving instructions for the next stop completely before you head out as sometimes they will provide you with information about sites to look at enroute. Tour II starts at the William Osler Health Centre – Etobicoke General Hospital, 101 Humber College Boulevard. From Highway 27, turn east on Humber College Boulevard. After you pass the lights at Westmore Drive, turn right at the entrance roadway into the hospital grounds. Follow this roadway as it turns right in front of the main building. STOP on the side of this roadway, facing west, where safe and not obstructing traffic.

Northern Etobicoke had excellent soil for agriculture, and was soon specializing in wheat, dairy, livestock and fruit farming. Because the area was used almost exclusively for farming, the population was sparser than southern Etobicoke, and there were only four communities large enough to have a post office: Highfield, Smithfield, Claireville and Thistletown.

A map of Etobicoke made in the early 1940s shows that northern Etobicoke was still primarily farmland with the same four villages. But World War II changed all that, and northern Etobicoke quickly became a suburban centre that provided jobs and homes for a burgeoning post-war population.

This tour highlights the pioneer history of this area and you will see all of the sites that have survived from the 19th century. It will also cover some aspects of modern history, focusing on the time period after World War II when the area saw unprecedented growth. In addition to having large residential areas and parks, northern Etobicoke has a significant number of industrial and commercial properties, and although all but one of the farms have disappeared, a few parcels of land still remain undeveloped.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS will be found in italics and located after each stop. Read the driving instructions for the next stop completely before you head out as sometimes they will provide you with information about sites to look at enroute. Tour II starts at the William Osler Health Centre – Etobicoke General Hospital, 101 Humber College Boulevard. From Highway 27, turn east on Humber College Boulevard. After you pass the lights at Westmore Drive, turn right at the entrance roadway into the hospital grounds. Follow this roadway as it turns right in front of the main building. STOP on the side of this roadway, facing west, where safe and not obstructing traffic.

Starting Point (Map A): William Osler Health Centre

In 1964, 300,000 Etobicoke residents were being served by the 300-bed Queensway Hospital at Evans Avenue and The West Mall. Etobicoke General Hospital (EGH) was incorporated in 1965 and Etobicoke’s Council set aside six hectares of land for this new hospital here on the east side of Highway 27, north of the West Humber River. There was soon a huge campaign underway to raise money for the hospital, supported by 75 doctors and dentists, and many businesses, service clubs and individuals. In 1967, most Etobicoke schools held special fundraising events, such as car washes and walks. The sod was turned in 1968, and the new hospital was opened on September 20, 1972. By the end of that year, the hospital had served 1230 patients. The hospital’s auxiliary was formed in 1965, and by 1995 they had raised over $3,000,000 in support of the hospital.

In 1998, the province joined EGH with the hospitals in Brampton and Halton Hills to become the William Osler Health Centre, the largest community hospital corporation in Ontario. Osler's emergency departments are among the busiest in the province, and its labour and delivery program is one of the largest in the GTA. However, by 2015, the three locations were unable to meet the needs of a growing population, so a massive expansion of its services was undertaken. In Etobicoke, emergency care capacity has already been doubled, and its patient capacity will be quadrupled by the end of 2019.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue west along the hospital roadway to the stop sign. Turn right at “T” intersection and return to Humber College Boulevard. Turn left. Pass through stop lights at Highway 27, and enter the Humber College property. Turn left at the first street, which has a sign displaying a large “A”. You are now on Arboretum Boulevard. Follow it west to the security kiosk, which is staffed 7:00 am to 3:30 pm, Monday to Friday. If it is during those hours, advise the guard that you are there to visit the arboretum and the guard will advise you where you may park for no charge. If there is no guard, continue along Arboretum Boulevard; it will veer right and you will see the entrance roadway to the arboretum on your left where you can STOP.

In 1998, the province joined EGH with the hospitals in Brampton and Halton Hills to become the William Osler Health Centre, the largest community hospital corporation in Ontario. Osler's emergency departments are among the busiest in the province, and its labour and delivery program is one of the largest in the GTA. However, by 2015, the three locations were unable to meet the needs of a growing population, so a massive expansion of its services was undertaken. In Etobicoke, emergency care capacity has already been doubled, and its patient capacity will be quadrupled by the end of 2019.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue west along the hospital roadway to the stop sign. Turn right at “T” intersection and return to Humber College Boulevard. Turn left. Pass through stop lights at Highway 27, and enter the Humber College property. Turn left at the first street, which has a sign displaying a large “A”. You are now on Arboretum Boulevard. Follow it west to the security kiosk, which is staffed 7:00 am to 3:30 pm, Monday to Friday. If it is during those hours, advise the guard that you are there to visit the arboretum and the guard will advise you where you may park for no charge. If there is no guard, continue along Arboretum Boulevard; it will veer right and you will see the entrance roadway to the arboretum on your left where you can STOP.

Stop Two (Map B): Humber College

In response to the need for a more highly skilled workforce, the Ontario government passed legislation in 1967 to allow Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology (CAATs) to be established. Humber College opened its second location here in northern Etobicoke in 1968. The College was built on farm land originally owned by the William Mead family and later by the Jonathan Ackrow family. When it opened, the college received much criticism for its lack of basic amenities. There was no water for drinking and toilets, requiring many trips to nearby Ascot Hotel on Rexdale Boulevard. Mud and puddles surrounded the buildings; there was no public transit; and road access was poor.

Humber College soon overcame its initial difficulties and has been growing ever since. An Equine Centre opened in 1973 in the Ackrow’s former barn complex, although the centre was closed and the barns demolished in the mid-1980s. At the same time, two 19th century farm homes (one dating back to the 1830s) were also demolished.

An arboretum opened in 1977 and a nature centre with extensive trails in 1987, all of which are open to the public during daylight hours. The nature centre has recently become the Gold LEED-certified Centre for Urban Ecology where the college operates a variety of nature programs. Today, this Humber College site serves 15,000 students and confers both diplomas and degrees.

Humber College soon overcame its initial difficulties and has been growing ever since. An Equine Centre opened in 1973 in the Ackrow’s former barn complex, although the centre was closed and the barns demolished in the mid-1980s. At the same time, two 19th century farm homes (one dating back to the 1830s) were also demolished.

An arboretum opened in 1977 and a nature centre with extensive trails in 1987, all of which are open to the public during daylight hours. The nature centre has recently become the Gold LEED-certified Centre for Urban Ecology where the college operates a variety of nature programs. Today, this Humber College site serves 15,000 students and confers both diplomas and degrees.

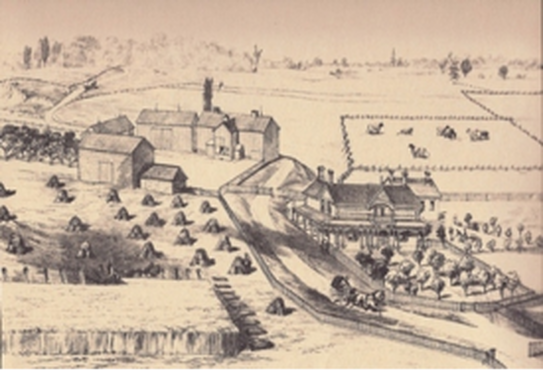

Ackrow Farm, east side of Highway 27, north of West Humber River c. 1919, looking

north. House on right built late 1830s. Barn complex on left had several barns in U-shape

creating an open court facing south. Horses and their driver are in the river valley.

Buildings demolished in 1985. Now site of Humber College. (Credit: Etobicoke Historical Society)

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Highway 27 and turn right. Drive south to the next street, Queen’s Plate Drive, and turn right. Turn left to enter the Woodbine Centre parking lot and STOP in the southeast corner of the lot, facing the Highway 27 and Rexdale Boulevard intersection.

Stop Three (Map C): Rexdale Boulevard and Village of Highfield

Welcome to what was once “downtown” Highfield, a small community that grew up along Rexdale Boulevard at the Third Concession (now Highway 27) consisting, at its peak, of two schools, a hotel, a church, a workshop, a store, a shoemaker, a blacksmith, a tailor, a milliner, and several houses.

Rexdale Boulevard was planned in 1833 to be an east-west road, mid-way between Dixon Road and Steeles Avenue, but the large valley of the West Humber River was such a significant barrier that its builders were forced to move the road’s starting point at Islington Avenue further south to its current location. The road was built by the partnership of John McVean and Elisha Lawrence, who named it McVean’s Road after John’s father, Alexander, who lived in Toronto Gore Township near the road’s western terminus. At different times the road has been called New Road, Toronto Gore Road, Old Malton Road, and Brampton Road. The name was changed to Rexdale Boulevard c. 1952 when Rex Heslop developed the Rexdale subdivision at the road’s eastern end.

In 1837, John Gardhouse settled in Etobicoke with his family. By 1878, John and his son, James, owned almost 200 hectares of land in northwestern Etobicoke, including a lot on the northeast and southeast corners of Rexdale Boulevard and Highway 27. In the early 1860s, John and James built an impressive home there called “Rosedale” where they imported and bred horses, Shorthorn cattle, Cotswold sheep and Berkshire pigs.

In 1928, the West Toronto Kiwanis Club bought 4 hectares beside a river from the Gardhouses and built Camp Westowanis for disadvantaged children. After 20 years, the land and all buildings were purchased by the St. Stanislaus Polish Parish in downtown Toronto and the name changed to Camp Polonia. Frank Deakin, who owned Etobicoke’s Pine Point Golf Course, bought the remainder of the Rosedale Farm, renaming it Janet Farm. He acquired the property for the Christian Brothers, who hoped to build a Training School for Boys on the property. In 1956, the land was transferred to the Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation. However, the area was too remote to obtain water and sewer services economically, so the school was never built. Portions of the original Rosedale farm land remain vacant today.

Rexdale Boulevard was planned in 1833 to be an east-west road, mid-way between Dixon Road and Steeles Avenue, but the large valley of the West Humber River was such a significant barrier that its builders were forced to move the road’s starting point at Islington Avenue further south to its current location. The road was built by the partnership of John McVean and Elisha Lawrence, who named it McVean’s Road after John’s father, Alexander, who lived in Toronto Gore Township near the road’s western terminus. At different times the road has been called New Road, Toronto Gore Road, Old Malton Road, and Brampton Road. The name was changed to Rexdale Boulevard c. 1952 when Rex Heslop developed the Rexdale subdivision at the road’s eastern end.

In 1837, John Gardhouse settled in Etobicoke with his family. By 1878, John and his son, James, owned almost 200 hectares of land in northwestern Etobicoke, including a lot on the northeast and southeast corners of Rexdale Boulevard and Highway 27. In the early 1860s, John and James built an impressive home there called “Rosedale” where they imported and bred horses, Shorthorn cattle, Cotswold sheep and Berkshire pigs.

In 1928, the West Toronto Kiwanis Club bought 4 hectares beside a river from the Gardhouses and built Camp Westowanis for disadvantaged children. After 20 years, the land and all buildings were purchased by the St. Stanislaus Polish Parish in downtown Toronto and the name changed to Camp Polonia. Frank Deakin, who owned Etobicoke’s Pine Point Golf Course, bought the remainder of the Rosedale Farm, renaming it Janet Farm. He acquired the property for the Christian Brothers, who hoped to build a Training School for Boys on the property. In 1956, the land was transferred to the Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation. However, the area was too remote to obtain water and sewer services economically, so the school was never built. Portions of the original Rosedale farm land remain vacant today.

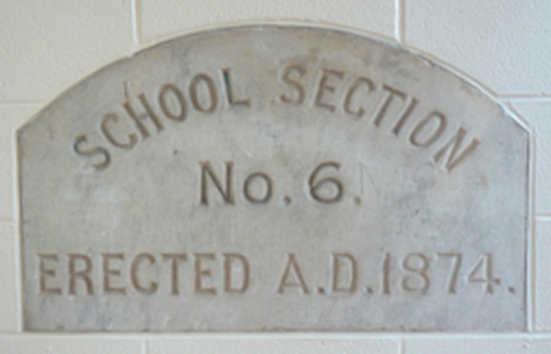

In 1845, a school was built east of here on the corner of Rexdale Boulevard and the Second Concession (now Martin Grove Road.) In 1874, it was replaced by a red and buff brick school built on the southeast corner of Rexdale Boulevard and Highway 27 on land purchased from James & Ann Gardhouse. This school closed in 1954 and was demolished in 1956. In 1964, a new Highfield Junior School was opened at 85 Mount Olive Drive, north of Albion Road and west of Martin Grove Road – a long way from the former village of Highfield. Nevertheless, the lobby of this new school displays the school section/date stone from the 1874 Highfield school.

In 1840, one of the first Roman Catholic schools in rural Ontario was built near the Fourth Concession (now Highway 427), on the site of what is now the Disco Road Waste Transfer Station, southwest of here. It was built of logs, with a door hung on leather hinges. The school appears to have been gone by 1872.

A Highfield post office opened in 1866 on the southwest corner of Rexdale Boulevard and Highway 27, remaining open until 1913. Today, that corner is the site of Woodbine Racetrack. E.P. (Edward Plunkett) Taylor, a director of the Ontario Jockey Club, saw the area from an airplane in 1947 and envisioned it as a good location for a new racetrack. In 1952, he bought 400 acres on behalf of the Jockey Club for $1,550 per acre, soon increasing the area to 830 acres. The racetrack opened in 1956, and the Queen’s Plate has been held there ever since. Taylor bought up many smaller race tracks in the Toronto area and closed them to push customers towards this new racetrack.

Since 1997, Woodbine has been the permanent home of the Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame. It is the only racetrack in North America that can hold both thoroughbred and harness races on the same day. In 2000, more than 1800 slot machines were added, and after this the Ontario Jockey Club, founded in 1881, was renamed Woodbine Entertainment Group. Two heritage farm homes and a barn that had stood on this property since the mid-19th century were demolished in the 1990s.

A Highfield post office opened in 1866 on the southwest corner of Rexdale Boulevard and Highway 27, remaining open until 1913. Today, that corner is the site of Woodbine Racetrack. E.P. (Edward Plunkett) Taylor, a director of the Ontario Jockey Club, saw the area from an airplane in 1947 and envisioned it as a good location for a new racetrack. In 1952, he bought 400 acres on behalf of the Jockey Club for $1,550 per acre, soon increasing the area to 830 acres. The racetrack opened in 1956, and the Queen’s Plate has been held there ever since. Taylor bought up many smaller race tracks in the Toronto area and closed them to push customers towards this new racetrack.

Since 1997, Woodbine has been the permanent home of the Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame. It is the only racetrack in North America that can hold both thoroughbred and harness races on the same day. In 2000, more than 1800 slot machines were added, and after this the Ontario Jockey Club, founded in 1881, was renamed Woodbine Entertainment Group. Two heritage farm homes and a barn that had stood on this property since the mid-19th century were demolished in the 1990s.

Woodbine Shopping Centre opened here in 1985 with an indoor amusement park called Fantasy Fair that includes a 1911 antique carousel, hand carved in the U.S. by Charles Looff. Each horse is valued at $30,000 today. This park also has a 16 metre diameter Ferris wheel and seven other rides. Over seven million guests have visited Fantasy Fair since it opened.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: There is no safe place to park in front of the next stop, Sharon Cemetery. It is recommended that you park in the southwest corner of the Woodbine Centre parking lot and walk west on the north side of Rexdale Boulevard to the cemetery, which is behind a chain link fence on your left.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: There is no safe place to park in front of the next stop, Sharon Cemetery. It is recommended that you park in the southwest corner of the Woodbine Centre parking lot and walk west on the north side of Rexdale Boulevard to the cemetery, which is behind a chain link fence on your left.

Stop Four (Map D): Sharon Cemetary

About 1838, lay preacher William Hainstock and his wife, Ann, moved to Highfield and by 1842 had opened their home for church services led by itinerant pastors. In 1843, Hainstock built a log church here on land donated by Richard Thomas, with a cemetery to the west. In 1856, the log cabin was replaced with a small red brick church, called Hainstock’s Primitive Methodist Church. The name was changed to Sharon Methodist Church in 1884 and then to Sharon United Church in 1925. The church was demolished in 1967, but the cemetery beside it remains.

Between 2005 and 2008, Sharon Cemetery underwent a complete restoration. A monument was erected listing the 57 families whose ancestors are buried there, including Appleby, Codlin, Gardhouse, Hainstock, and Thomas. (See photo on front cover.) This cemetery is the only surviving 19th century property from the pioneer community of Highfield and is now a designated heritage site. You may enter through the gate to explore the cemetery; please close the gate securely when you leave.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Rexdale Boulevard and turn right. Turn right at Humberwood Boulevard, a short distance past Sharon Cemetery. As you drive north, you will pass through the 1990s Humberwood subdivision – an indication of how recently some parts of northern Etobicoke have been developed. Look on both sides of the road and note that except for two condo towers, almost all residential development is on the west side of the road. This is because of the wide West Humber River valley on the right – that same valley that caused early road builders to divert the east end of Rexdale Boulevard so far south. After you pass through the stop lights at Morning Star Drive, turn right at the first driveway into the Humberwood Centre parking lot and STOP where possible.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Rexdale Boulevard and turn right. Turn right at Humberwood Boulevard, a short distance past Sharon Cemetery. As you drive north, you will pass through the 1990s Humberwood subdivision – an indication of how recently some parts of northern Etobicoke have been developed. Look on both sides of the road and note that except for two condo towers, almost all residential development is on the west side of the road. This is because of the wide West Humber River valley on the right – that same valley that caused early road builders to divert the east end of Rexdale Boulevard so far south. After you pass through the stop lights at Morning Star Drive, turn right at the first driveway into the Humberwood Centre parking lot and STOP where possible.

Stop Five (Map E): Woodbine Downs and Humberwood Subdivisions

You are in the parking lot of the award-winning Humberwood Centre, the first such facility in Ontario, opened here in 1996 at a cost of $23,000,000. It consists of two elementary schools, a library, a daycare centre and a public recreation centre, all under one roof. Although the Centre is surrounded on three sides by the West Humber River valley, it has been designed to help control flooding by using techniques such as porous pavement and naturalized landscaping.

On the east side of the parking lot are signs indicating the starting point of a six kilometre/two hour Discovery Walking Trail that leads through the West Humber River valley to the Humber Arboretum and back, built by a partnership among the City of Toronto, the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) and Humber College.

In the 1960s, “Woodbine Downs” was conceived as a new subdivision that would have fine residences, a golf course, commerce and industry. It was to run from Rexdale to Steeles, and from Highway 27 to Indian Line (now Highway 427), an area that was almost exclusively farm land. However, the golf course wasn’t built because Metropolitan Toronto and the Metropolitan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (MTRCA) could not agree on the plans. Instead, the MTRCA kept the valley land for public parkland, as well as flood control. Claireville Dam was built on the West Humber River in 1964, on the west side of Indian Line, with a surrounding 848 acre conservation area that straddles Peel and Toronto.

Delays in the development of Woodbine Downs were also caused by the Toronto Airport’s objections to large scale residential development under a flight path. In addition, a 1967 report on roads in northern Etobicoke reported potential major changes to the area in the near future, including the creation of Highway 427 and the extension of Finch Avenue west across Etobicoke from Islington Avenue.

As a result, Woodbine Downs as originally conceived was never built. However, a smaller Woodbine Downs community was finally built on the south side of Finch, west of Highway 27, in the 1980s. You can see the homes and apartment buildings of Woodbine Downs just north of your current location, above the river valley. As you have already seen, the Humberwood subdivision was built in the 1990s by Greenpark, west of where you are now standing.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Humberwood Boulevard and turn right. In the mid-1990s, the Woodbine Downs and Humberwood neighbourhoods were linked by a bridge just north of here. As you drive over this bridge, look left into the beautiful West Humber River valley. Until the 1990s, the farm houses of the Thomas and George Appleby family and the Matthew Codlin family overlooked this valley. The Appleby farm was on the south side of the valley facing north, while the Codlin house was on the north side facing south, both with lovely views. They are two more examples of well-preserved, 150 year old heritage homes that have been recently lost to development.

On the east side of the parking lot are signs indicating the starting point of a six kilometre/two hour Discovery Walking Trail that leads through the West Humber River valley to the Humber Arboretum and back, built by a partnership among the City of Toronto, the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) and Humber College.

In the 1960s, “Woodbine Downs” was conceived as a new subdivision that would have fine residences, a golf course, commerce and industry. It was to run from Rexdale to Steeles, and from Highway 27 to Indian Line (now Highway 427), an area that was almost exclusively farm land. However, the golf course wasn’t built because Metropolitan Toronto and the Metropolitan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (MTRCA) could not agree on the plans. Instead, the MTRCA kept the valley land for public parkland, as well as flood control. Claireville Dam was built on the West Humber River in 1964, on the west side of Indian Line, with a surrounding 848 acre conservation area that straddles Peel and Toronto.

Delays in the development of Woodbine Downs were also caused by the Toronto Airport’s objections to large scale residential development under a flight path. In addition, a 1967 report on roads in northern Etobicoke reported potential major changes to the area in the near future, including the creation of Highway 427 and the extension of Finch Avenue west across Etobicoke from Islington Avenue.

As a result, Woodbine Downs as originally conceived was never built. However, a smaller Woodbine Downs community was finally built on the south side of Finch, west of Highway 27, in the 1980s. You can see the homes and apartment buildings of Woodbine Downs just north of your current location, above the river valley. As you have already seen, the Humberwood subdivision was built in the 1990s by Greenpark, west of where you are now standing.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Humberwood Boulevard and turn right. In the mid-1990s, the Woodbine Downs and Humberwood neighbourhoods were linked by a bridge just north of here. As you drive over this bridge, look left into the beautiful West Humber River valley. Until the 1990s, the farm houses of the Thomas and George Appleby family and the Matthew Codlin family overlooked this valley. The Appleby farm was on the south side of the valley facing north, while the Codlin house was on the north side facing south, both with lovely views. They are two more examples of well-preserved, 150 year old heritage homes that have been recently lost to development.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue on Humberwood Boulevard to Humberline Drive and turn left. Continue north. The straight section of Humberline Drive north of Finch Avenue is one of two remaining pieces of the original Fourth Concession road that ran from Rathburn to Steeles. (The other section can be found along Carlingview Drive further south.) Note on your right the large, open area that remains undeveloped. Turn left on Claireville Drive and STOP opposite the entrance gates to #61, the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir. Alternatively, if between 9:00 am and 6:00 pm daily, you can check in with the security guard in their entrance kiosk, enter the front gates, and STOP in their parking lot for a closer look at the Mandir.

Stop Six (Map F): BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir

The BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir is a place of worship and prayer for Hindus. The Haveli or entrance lobby is at the east end of the complex with a large hand-carved doorway of Burmese teak. Inside, a magnificent courtyard of this same intricately-carved teak is a place to gather. This building also includes prayer rooms, a museum on Indian and Indo-Canadian heritage, and a gift shop.

The actual Mandir is at the west end of the complex. This magnificent structure is made of 24,000 pieces of white Turkish limestone, translucent Italian Carrera marble, and Indian pink stone, all intricately hand-carved in India. After carving, the pieces (which weigh over 5500 tonnes) were shipped to Toronto and assembled by 1800 crafters without the use of structural steel or nails. The ethereal effect of light on the stone creates a calming environment for prayer, meditation and inspiration. The total construction cost of the Mandir was over $40,000,000. It was opened and dedicated to the people of Canada on July 22, 2007.

The actual Mandir is at the west end of the complex. This magnificent structure is made of 24,000 pieces of white Turkish limestone, translucent Italian Carrera marble, and Indian pink stone, all intricately hand-carved in India. After carving, the pieces (which weigh over 5500 tonnes) were shipped to Toronto and assembled by 1800 crafters without the use of structural steel or nails. The ethereal effect of light on the stone creates a calming environment for prayer, meditation and inspiration. The total construction cost of the Mandir was over $40,000,000. It was opened and dedicated to the people of Canada on July 22, 2007.

If you have time, the complex is open to all visitors from 9:00 am to 6:00 pm daily. There is no admission charge to the Haveli or Mandir, but there is a nominal fee for the museum. Because it is a sacred place, visitors must follow certain regulations: shoulders and knees must be covered (wraps provided free, if needed); footwear must be removed (racks provided for shoes); photographs and videos may be taken of the exterior only; no food, drinks, cell phones, pets or smoking are allowed. Inside the Mandir, silence must be maintained and the stonework may not be touched; anyone 17 or younger must be accompanied by an adult.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue north on Claireville Drive until it rejoins Humberline Drive. Turn left and drive north to Albion Road. Turn left, and after you go under Highway 427, turn right at the next street, Codlin Crescent. After Codlin Crescent veers to the left, STOP on the right side of the road, facing west, as close to the next road, Alcide Street, as possible.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue north on Claireville Drive until it rejoins Humberline Drive. Turn left and drive north to Albion Road. Turn left, and after you go under Highway 427, turn right at the next street, Codlin Crescent. After Codlin Crescent veers to the left, STOP on the right side of the road, facing west, as close to the next road, Alcide Street, as possible.

NOTE: In Google Maps, this stop represents the end of the driving instructions in Part A of this tour. Instructions for Part B begin now, and map lettering re-starts from B in the new section of this tour, starting below.

Stop Seven (Map B): Village of Claireville

Until the late 1980s, Codlin Crescent here was Albion Road and was the peaceful, tree-lined main street of the 19th century village of Claireville. This village surrounded the intersection of Indian Line/Highway 50, Steeles Avenue and Albion Road, and overlapped three townships: Etobicoke, Vaughan and Toronto Gore. The community began in 1832 with the opening of John Dark’s Halfway House on the southwest corner of Steeles Av. and Indian Line. The “Humber” post office opened in Bowman’s General Store in 1842.

The “Father” of Claireville village is considered to have been Jean du Petit Pont de la Haye. Born in France in 1799, he was an ardent Bonapartist who left because his beliefs were not in harmony with the current Bourbon regime. He went to Britain to teach in 1828, and while there met the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, Sir John Colborne, who asked him to be the French Master at Upper Canada College (UCC) in Toronto, which was opening in 1829. De la Haye taught French at UCC for 27 years.

Although de la Haye lived with his family on the UCC campus when school was in session, in 1840 he built a country home called Les Ormes (The Elms), west of Indian Line, south of Steeles, in Toronto Gore Township. At the same time, he also purchased the 40 hectare Lot 40, Concession 4, in the very northwest corner of Etobicoke, and in 1851 registered a plan for a town there to be called Claireville, after the eldest of his six daughters, Claire. Another town road, Alcide Street, was named after his son, who became a physician in Toronto.

The “Father” of Claireville village is considered to have been Jean du Petit Pont de la Haye. Born in France in 1799, he was an ardent Bonapartist who left because his beliefs were not in harmony with the current Bourbon regime. He went to Britain to teach in 1828, and while there met the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, Sir John Colborne, who asked him to be the French Master at Upper Canada College (UCC) in Toronto, which was opening in 1829. De la Haye taught French at UCC for 27 years.

Although de la Haye lived with his family on the UCC campus when school was in session, in 1840 he built a country home called Les Ormes (The Elms), west of Indian Line, south of Steeles, in Toronto Gore Township. At the same time, he also purchased the 40 hectare Lot 40, Concession 4, in the very northwest corner of Etobicoke, and in 1851 registered a plan for a town there to be called Claireville, after the eldest of his six daughters, Claire. Another town road, Alcide Street, was named after his son, who became a physician in Toronto.

A generous, egalitarian man, de la Haye donated church sites in Claireville to three different church denominations: Congregationalists in 1842, Primitive Methodists in 1846, and Roman Catholics in 1860. He was a director and majority shareholder of the Albion Plank Road Company, incorporated in 1846 to build an improved road from Thistletown, through Claireville, and west into Peel County. After de la Haye retired, he became a justice of the peace and a member of the Toronto Gore Township Council.

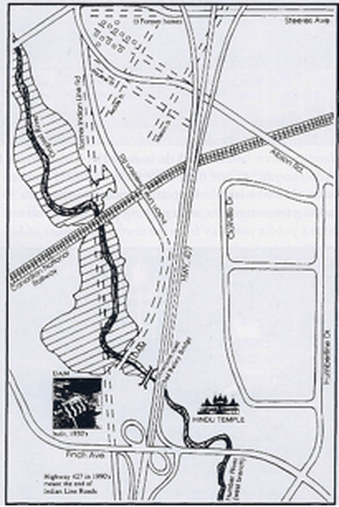

Claireville grew, and by 1870 the population was 175. There were two hotels, two general stores, one butcher, one blacksmith, one tailor, one cabinet maker, a toll gate, and a steam-operated flour mill. After reaching a peak just after World War II, Claireville has declined steadily until only a few buildings remain today. In fact, in a township that has seen many changes since World War II, this area has been referred to as “the most changed area of Etobicoke”. These changes came about primarily as a result of building Highway 427 in the late 1980s, which obliterated Indian Line. (Indian Line ran along the original 1787 survey line drawn to define the western boundary of the Toronto Purchase made with the Mississauga First Nation.) The new Highway 427 resulted in major property expropriations, tree removals, and road realignments. Albion Road was diverted to the south and Steeles Avenue was diverted north into Vaughan Township, bypassing the village. Two streets were completely closed (William and Pauline), and Alcide Street was moved 64 metres further west.

What had once been Albion and Steeles within Claireville were joined at their western ends to become Codlin Crescent, named after the local pioneer family.

Claireville grew, and by 1870 the population was 175. There were two hotels, two general stores, one butcher, one blacksmith, one tailor, one cabinet maker, a toll gate, and a steam-operated flour mill. After reaching a peak just after World War II, Claireville has declined steadily until only a few buildings remain today. In fact, in a township that has seen many changes since World War II, this area has been referred to as “the most changed area of Etobicoke”. These changes came about primarily as a result of building Highway 427 in the late 1980s, which obliterated Indian Line. (Indian Line ran along the original 1787 survey line drawn to define the western boundary of the Toronto Purchase made with the Mississauga First Nation.) The new Highway 427 resulted in major property expropriations, tree removals, and road realignments. Albion Road was diverted to the south and Steeles Avenue was diverted north into Vaughan Township, bypassing the village. Two streets were completely closed (William and Pauline), and Alcide Street was moved 64 metres further west.

What had once been Albion and Steeles within Claireville were joined at their western ends to become Codlin Crescent, named after the local pioneer family.

Only 14 buildings from the old village remain, and many are empty or being used for businesses that require heavy truck traffic. The following mini-tour of the village of Claireville will tell you more about those that remain, as well as a few that have vanished.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Drive slowly west along Codlin Crescent to learn more about the buildings on the north side of Codlin Crescent.

No. 2128: This property was originally purchase in 1877 by widow Elizabeth Wiley, and it was owned by her descendants until 1963. The house was built c. 1926 in the Edwardian Classical style popular at that time. Characteristics of this style include a solid, square design of red brick with a gabled roof line and a large open front porch. Today the house is used for storage.

No. 2136: This property was separated from the lot to the west in 1940 and purchased by Crozier Keyes, who built a house and lived here until 1973. The property was sold to Ernesto and Anna Di Sanctis who operated a sodding and paving company until 1993.

No. 2140: This property was vacant until purchased by James Linton in 1884. C. 1889, James built a house in a Gothic Revival style with a small gable peak over the front door. It is the second oldest building remaining in Claireville. (From 1870 to 1895 Linton and his brother, John, owned a general store at the southeast corner of Albion Road and Indian Line where James was the village post master.) In 1895 Linton sold this property to Matthew Codlin who lived there with his son William and their families. In 1945, the house was sold to George Rowntree and his wife Eva, members of another large pioneer family that you will learn about later in this tour. George worked for A.V. Roe in Malton and in 1962 retired to Burk’s Falls.

No. 2150: This property was owned by James and Margaret Hewgill from 1886 to 1913. They were members of a large Yorkshire family who had settled in Peel County. The house is believed to have been built c. 1915 by Edward Moody. From 1919 to 1960, it was owned by members of the Curran family: John and Theresa until 1956, followed by William and Eleanor.

No. 2152: This property was purchased in 1923 by Albert and Gertrude Kitchener, members of a family that once owned five houses in Claireville, building at least three of them. No.2152 was built in 1941 by Albert and his son Charlie. Albert died in 1947, and in 1953 Gertrude transferred the property to Charlie and his wife Mary. Charlie worked as a mechanic for Bristol Aviation and Mary worked at the Hospital for Sick Children in Thistletown. After Charlie died, Mary sold the property in 1979. The rear part of this property was once the location of a Primitive Methodist church, built in 1846 on a small triangular piece of land donated by de la Haye, and that faced north onto what became Steeles Avenue West. In 1883, the church was bought by Christian evangelists called the Plymouth Brethren and used as their gospel hall until 1947. After that, it was used as a homeless shelter and a garage, before finally being demolished in the early 1990s. A 1.5 metre wide right-of-way still exists up the east side of this property, once the foot path from Albion Road to the church.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Drive slowly west along Codlin Crescent to learn more about the buildings on the north side of Codlin Crescent.

No. 2128: This property was originally purchase in 1877 by widow Elizabeth Wiley, and it was owned by her descendants until 1963. The house was built c. 1926 in the Edwardian Classical style popular at that time. Characteristics of this style include a solid, square design of red brick with a gabled roof line and a large open front porch. Today the house is used for storage.

No. 2136: This property was separated from the lot to the west in 1940 and purchased by Crozier Keyes, who built a house and lived here until 1973. The property was sold to Ernesto and Anna Di Sanctis who operated a sodding and paving company until 1993.

No. 2140: This property was vacant until purchased by James Linton in 1884. C. 1889, James built a house in a Gothic Revival style with a small gable peak over the front door. It is the second oldest building remaining in Claireville. (From 1870 to 1895 Linton and his brother, John, owned a general store at the southeast corner of Albion Road and Indian Line where James was the village post master.) In 1895 Linton sold this property to Matthew Codlin who lived there with his son William and their families. In 1945, the house was sold to George Rowntree and his wife Eva, members of another large pioneer family that you will learn about later in this tour. George worked for A.V. Roe in Malton and in 1962 retired to Burk’s Falls.

No. 2150: This property was owned by James and Margaret Hewgill from 1886 to 1913. They were members of a large Yorkshire family who had settled in Peel County. The house is believed to have been built c. 1915 by Edward Moody. From 1919 to 1960, it was owned by members of the Curran family: John and Theresa until 1956, followed by William and Eleanor.

No. 2152: This property was purchased in 1923 by Albert and Gertrude Kitchener, members of a family that once owned five houses in Claireville, building at least three of them. No.2152 was built in 1941 by Albert and his son Charlie. Albert died in 1947, and in 1953 Gertrude transferred the property to Charlie and his wife Mary. Charlie worked as a mechanic for Bristol Aviation and Mary worked at the Hospital for Sick Children in Thistletown. After Charlie died, Mary sold the property in 1979. The rear part of this property was once the location of a Primitive Methodist church, built in 1846 on a small triangular piece of land donated by de la Haye, and that faced north onto what became Steeles Avenue West. In 1883, the church was bought by Christian evangelists called the Plymouth Brethren and used as their gospel hall until 1947. After that, it was used as a homeless shelter and a garage, before finally being demolished in the early 1990s. A 1.5 metre wide right-of-way still exists up the east side of this property, once the foot path from Albion Road to the church.

No. 2154: This property was originally part of the same lot as No. 2152. In 1948, Gertrude Kitchener sold the west half to Milt and Mary Hewgill, who built a house and lived here until 1973.

No. 2158: It is believed that this modest Gothic-style house was built in the early 1900s. As recently as the mid-1970s, there was gingerbread trim in the peak of the front gable, and it still has an attractive bay window in front. The original open verandah has been enclosed. The house was purchased by Albert and Gertrude Kitchener in 1944, but occupied by their son, Lorne. Gertrude owned the property until her death in 1980. The building is now home to the Bhagwan Valmiki Hindu Temple.

No. 2158: It is believed that this modest Gothic-style house was built in the early 1900s. As recently as the mid-1970s, there was gingerbread trim in the peak of the front gable, and it still has an attractive bay window in front. The original open verandah has been enclosed. The house was purchased by Albert and Gertrude Kitchener in 1944, but occupied by their son, Lorne. Gertrude owned the property until her death in 1980. The building is now home to the Bhagwan Valmiki Hindu Temple.

Next door to No. 2158 to the west was Steve Dicken’s blacksmith shop, built in the 1850s and moved to Woodbridge in 1919. The property was purchased by Albert and Gertrude Kitchener in 1923 and they built a house and a service station with a small store. After Albert died in 1947, the service station remained under Gertrude’s ownership, but was operated by their son, Lorne, as a Supertest station until the house and service station were expropriated and demolished by the City of Etobicoke in 1983.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Do a U-turn and drive slowly east along Codlin Crescent to learn more about the buildings on the south side of the street.

No. 2119: This modest Gothic-revival style house was likely built c. 1887 by Mary Porter. The property was sold to William and Jessie Kitchener in 1907, who owned it until 1920. It was then bought by William’s father, Thomas, in 1921, and when he died in 1935, it passed to Thomas’ grandson, Everton, and his wife, Myra. Everton owned a threshing machine which he would take from farm to farm during harvest season. Later he worked in maintenance at Toronto International Airport. When Myra died in 1972, Everton married her sister-in-law, Isabel Rowntree, in 1973. The house was sold after Everton passed away in 1981. As recently as the mid-1970s the front gable eaves were still trimmed with gingerbread. There is an attractive bay window at the front, with two tall, narrow windows above on the second floor.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Do a U-turn and drive slowly east along Codlin Crescent to learn more about the buildings on the south side of the street.

No. 2119: This modest Gothic-revival style house was likely built c. 1887 by Mary Porter. The property was sold to William and Jessie Kitchener in 1907, who owned it until 1920. It was then bought by William’s father, Thomas, in 1921, and when he died in 1935, it passed to Thomas’ grandson, Everton, and his wife, Myra. Everton owned a threshing machine which he would take from farm to farm during harvest season. Later he worked in maintenance at Toronto International Airport. When Myra died in 1972, Everton married her sister-in-law, Isabel Rowntree, in 1973. The house was sold after Everton passed away in 1981. As recently as the mid-1970s the front gable eaves were still trimmed with gingerbread. There is an attractive bay window at the front, with two tall, narrow windows above on the second floor.

Immediately west of this house was the home of Percy Kitchener. Beyond that, on the southwest corner of Albion Road and Indian Line, was the general store once owned by the Linton brothers. This store had many owners over the years, with its final occupant being Tinker’s Cleaners. Opposite this store, on the west side of Indian Line at Albion Road, was the house where Grant Kitchener grew up, built by his grandfather, Albert Kitchener. These three buildings were expropriated and demolished when road layouts were changed in the 1980s.

No. 2117: The 1842 frame Congregational Church was located on the rear of this property. It was built on land donated by de la Haye. The church was sold to an Anglican Church in 1897, who replaced it with a Gothic style two-toned brick building. After the congregation disbanded, the church building was owned from 1934 to 1959 by Edward and Ella Perry, who operated an apiary. The church was then used as a summer home for a few years, but its actual date of demolition is unknown. The property was purchased in 1976 by Antonio and Maria Figliomeni, who built a house and operate Anthony’s Garden Centre where the church had once been located.

No. 2115: Claireville’s Community Hall and Park Association was formed in 1860. In 1863, a community hall was erected by the Sons of Temperance Division No. 286. In 1903, it was purchased by another community organization called The Chosen Friends, who sold it in 1932 to the Claireville Community Hall and Park Association. In 1966, the hall was moved from this lot to the east side of Indian Line, south of Albion Road. For over 120 years, the hall was used for community events such as school concerts and socials, and the park was used for agricultural fairs, picnics and skating.Despite a community effort to save the Community Hall, it was demolished in 1986 when roads were realigned as a result of building Highway 427.

No. 2107: This building is believed to have been built c. 1912 by Maude McMahon, who lived here until 1941. It was purchased by Clifford and Catherine Fleury, who owned it until 1985. It is now the Bharat Sevashram Sangha, a spiritual and philanthropic brotherhood devoted to serving mankind.

No. 2103: This house was built c. 1919 in an Edwardian Classical style, very similar to No. 2128, by owner Martha Mellings who lived there until 1942. Today the house is owned by the Bharat Sevashram Sangha.

No. 2095: This is the oldest house remaining from old Claireville. Built in 1854, it is listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register. The Albion Plank Road tollgate in Claireville was originally located on Highway 50 at Gore Road, but by 1871, the tollgate had moved to this house and Christopher Armstrong was the tollgate keeper who lived there with his family. That makes this house one of only two known tollhouses remaining in Toronto.

No. 2103: This house was built c. 1919 in an Edwardian Classical style, very similar to No. 2128, by owner Martha Mellings who lived there until 1942. Today the house is owned by the Bharat Sevashram Sangha.

No. 2095: This is the oldest house remaining from old Claireville. Built in 1854, it is listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register. The Albion Plank Road tollgate in Claireville was originally located on Highway 50 at Gore Road, but by 1871, the tollgate had moved to this house and Christopher Armstrong was the tollgate keeper who lived there with his family. That makes this house one of only two known tollhouses remaining in Toronto.

The house is a modest example of a Neo-classical dwelling from the mid-19th century. Its basic design is a simple rectangular two-storey frame house, with a smaller two-storey wing intersecting at right angles on the south side. The roof gables all have prominent cornice returns, a common feature of the Neo-classical style, and an off-centre main entry door which appears to be original.

The last residential owners, Fred and Audrey Henderson, lived in the house for 42 years, operating Highland Evergreen Supply Limited from their home. In 2006, no longer able to live with the dramatic changes in Claireville, they reluctantly sold their home to its current owner, a truck and trailer storage business.

The last residential owners, Fred and Audrey Henderson, lived in the house for 42 years, operating Highland Evergreen Supply Limited from their home. In 2006, no longer able to live with the dramatic changes in Claireville, they reluctantly sold their home to its current owner, a truck and trailer storage business.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Albion Rd. Turn left and drive east. After you pass Carrier Drive, look for a cemetery on the left. Turn left into the cemetery’s SECOND driveway, just before the Highway 27 intersection. STOP on the right side of any of the cemetery’s internal streets.

Stop Eight (Map C): Glendale Memorial Gardens

Glendale Memorial Gardens was established in 1952 on 25 hectares of former farmland. This cemetery represented a new concept where the land was divided into areas called “gardens”, each with its own name and large central monument (for example, the “Garden of Devotion” has a large stone statue of an open bible.) Trees and shrubs were planted, and ponds were built to create a park-like setting.

No traditional headstones are permitted: individual graves are marked by bronze plaques lying flush with the ground.

This property was originally owned by William Jacobs and the style of the house would indicate it was built pre-1850. After the property was purchased by Glendale Memorial Gardens, the original 19th century farm house was preserved as the cemetery superintendant’s office until the 1990s when it was demolished.

No traditional headstones are permitted: individual graves are marked by bronze plaques lying flush with the ground.

This property was originally owned by William Jacobs and the style of the house would indicate it was built pre-1850. After the property was purchased by Glendale Memorial Gardens, the original 19th century farm house was preserved as the cemetery superintendant’s office until the 1990s when it was demolished.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Albion Road and turn left. Drive east to Martin Grove Road where you will turn left. As you go through the Albion Road and Martin Grove Road intersection, look at all four corners as this was once the centre of a pioneer village called Smithfield. There is no safe place to stop at the intersection, so we will talk about Smithfield at the next stop. Drive north on Martin Grove Road and turn left at the first street, Lexington Avenue. Turn right on the next street, Tealham Drive, and STOP on the right side of the road.

Stop Nine (Map D): Village of Smithfield and York Condominium No.1

Smithfield was a crossroads hamlet at the intersection of Albion Road and Martin Grove Road. A tollgate on the Albion Plank Road was located here from 1846 until the 1880s. At its peak, the village had two churches, a school, two blacksmiths, a tailor, a wagon maker and two butchers. A post office was opened on the northeast corner of the main intersection in 1899, but it was called “Etobicoke” because there was already a Smithfield post office in Northumberland County.

The village was named after Robert Smith and his three sons, who had a farm at the main intersection. In 1845, on the west side of Martin Grove Road, a quarter mile north of Albion Road, a Primitive Methodist church was built of logs. By 1886, the log church was replaced by a frame building on Albion Road, west of Martin Grove. It was later veneered in red and buff brick. This building survived until the 1960s.

Starting in 1845, children went to school in a building shared with Thistletown near Albion Road and Kipling Avenue, but in 1874, a new school was built in Smithfield on the north side of Albion Road, west of the Methodist Church. The Toronto Normal School (teachers’ college) used the Smithfield school as a “Model School” where student teachers could learn how to teach in a rural environment. The school was heated with two wood stoves until a basement was excavated and a furnace installed in 1925. Electricity was not installed until 1939. After it closed as a school in 1954, students were bussed to Thistletown. The 1874 school building served as a community centre until vandals destroyed it by fire in 1957.

In 1966, a new Smithfield Middle School opened at 175 Mount Olive Drive. The old 1874 school section stone (seen under the peak of the front gabled roof in photo above) is on display in the new school’s foyer, the only item remaining from old Smithfield.

In 1969, Burton Winberg’s Rockport Group built a townhouse complex between Martin Grove Road and Tealham Drive, north of Lexington Avenue. This 69-unit complex was registered as York Condominium Corporation No. 1 – the very first townhouse condominium corporation registered in Ontario.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Turn around and return to Lexington Avenue. Turn right. Cross Martin Grove Road into Garfella Drive straight ahead. Turn right at the first street, Stevenson Road. Turn left into Seguin Court and STOP as close to #5 as possible.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Turn around and return to Lexington Avenue. Turn right. Cross Martin Grove Road into Garfella Drive straight ahead. Turn right at the first street, Stevenson Road. Turn left into Seguin Court and STOP as close to #5 as possible.

Stop Ten (Map E): Albion Grove Village Subdivision

Garfella Drive was named after Garfield Ella, whose farm was subdivided to build Albion Grove Village. This was an “all-electric” subdivision, built by Jobert Construction in 1963. As part of a push to increase the use of “cheap, clean” electricity, Ontario Hydro initiated a program in 1957 that focused on conferring “Medallion” status on homes that met specific criteria: 100 amp electrical service; electric heating; at least one electric appliance installed and pre-wiring for four others; an electric “Cascade 40” water heater; a minimum of six inches of insulation in the roof and three inches in the walls; and double-paned, aluminum, storm and screen windows. In addition, the entire subdivision had buried wiring. In 1958, there was a model Medallion home on display at the CNE and, after that, homeowners were clamouring for this new world of “living better, electrically”.

To certify that a home was a true “all-electric” home, a doorbell unit was installed that included a round black and white medallion reading, “Medallion All-Electric Home – Live Better Electrically”. All of the homes in this area are Medallion homes, but only number 5 Seguin Court still has an original medallion on its doorbell.

The six original model homes for this subdivision were 136 Stevenson Road and 3 to 17 Seguin Court. The first four addresses are single family dwellings and the others are semi-detached. They represent the six distinctive styles that were offered in this subdivision, which stretches for many blocks east and north. Homes were listed from $15,495 to $19,418.

The six original model homes for this subdivision were 136 Stevenson Road and 3 to 17 Seguin Court. The first four addresses are single family dwellings and the others are semi-detached. They represent the six distinctive styles that were offered in this subdivision, which stretches for many blocks east and north. Homes were listed from $15,495 to $19,418.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Stevenson Road and turn right. Turn right at Garfella Drive and continue to Mount Olive Drive. Turn right onto Mount Olive and drive south. On the right, you will pass 85 Mount Olive Drive, Highfield Junior School, which contains the 1874 Highfield school section number/date-stone. Continue on Mount Olive Drive to Kipling Avenue. Cross Kipling Avenue into Panorama Court straight ahead. Just before the end of the street, veer right into the driveway for No. 51, formerly Thistletown Regional Centre for Children and Adolescents. STOP in the parking lot north of the large brick building

Stop Eleven (Map F): Former Thistletown Regional Centre for Children and Adolescents

In 1846, Alexander Card purchased 32 hectare Lot 36, Concession A, which ran from Islington Avenue to Kipling Avenue, north of what is now Finch Av. W. In 1847, Card sold a .6 hectare piece in the southwest corner to William Kaiting, who erected a grist mill on the west side and a saw mill on the east side of the Humber River, close to Islington Avenue. After the British Corn Laws were repealed in 1847 and free-trade introduced, Kaiting went bankrupt in 1848 and the mills were sold at auction.

In 1851, the Honourable Henry John Boulton Sr., son of the Honourable D’Arcy Boulton Sr., bought the mills, which he called Humberford Mills. In 1855 he built a large brick home called Humberford House just west of the mills. Darcy Sr. and Henry Sr. were both wealthy Toronto lawyers, judges and politicians. In 1857, Henry Sr. sold the property to his son, Henry John Boulton Jr., who hired tenants to manage the property. Boulton introduced several farming innovations, such as a tile system of land drainage that is still used today.

In 1851, the Honourable Henry John Boulton Sr., son of the Honourable D’Arcy Boulton Sr., bought the mills, which he called Humberford Mills. In 1855 he built a large brick home called Humberford House just west of the mills. Darcy Sr. and Henry Sr. were both wealthy Toronto lawyers, judges and politicians. In 1857, Henry Sr. sold the property to his son, Henry John Boulton Jr., who hired tenants to manage the property. Boulton introduced several farming innovations, such as a tile system of land drainage that is still used today.

By 1882, John Rowntree had acquired the .6 hectare piece of Lot 36 that included the Humberford Mills and House, which he sold to his son, George Rowntree for $1.00. That same year, George bought the remaining 32 hectares of Lot 36 from St. George Card, son of Alexander Card. George Rowntree’s wife, Angeline, sold the property in 1920 after George died.

In 1926, the property was bought by the Hospital for Sick Children to build a convalescent hospital to replace their Lakeside Home for Little Children at Hanlan’s Point. This new hospital was described as a “Palace of Sunshine”, designed for children requiring helio- or sun therapy and fresh air, or hospitalization for long periods, e.g. while recovering from rheumatic fever, tuberculosis, polio, surgery, etc. It opened on October 24, 1928 with 72 patients who arrived from the downtown hospital site in a celebratory “parade”. The building accommodated 112 patients in rooms with 6 to 8 cots. Each room opened onto a broad screened verandah so the cots could be wheeled outside in nice weather. The site was self sufficient, with its own steam plant, water filtration system and sewage-disposal. Electrical power could be generated with a steam turbine in the case of a power failure. On opening, 50,000 tree seedlings were planted.

Because of medical advances such as vaccinations and antibiotics, the need for this type of hospital diminished over time. During Hurricane Hazel in 1954, the last straw came when 17 babies in incubators had to be evacuated as the storm cut off the hydro for longer than hospital staff was able to manage. Soon after, the decision was made to close the facility.

In 1957, the property was sold to the Ontario Government to become Thistletown Regional Centre for Children and Adolescents, the first residential mental health centre for children and youths in Ontario. Minister of Health at that time, Dr. Mackinnon Phillips, optimistically predicted, “It is possible we will be able to cure almost all psychotic children.” It could accommodate 72 children aged six to seventeen. Initially, few staff members had experience working with disturbed children and when the hospital opened in January 1958, the staff had only received three months of training. In addition, the target population was ill-defined, and the first group included not just emotionally disturbed children, but also those with schizophrenia, brain damage, developmental delays, deafness, etc. This first cohort of children literally destroyed the place: broke windows, burned mattresses, ripped off doors, and attacked the workers. Staff largely learned as they went, and after a period of major adjustment and learning for all, order was brought to the place so that an era of effective treatment could begin.

As you read in Tour I about Warrendale, by the mid-1960s, a major learning for many in child psychiatry was the revelation that experiencing a group living situation can be healing to a child who previously had never lived in a “normal” family environment. In 1972, Thistletown Centre constructed ten small houses on the property, modelled on Warrendale, and moved most of the children out of a “hospital” setting into these cottages where they could experience living in family-style groups. The staff here referred to these homes, unofficially, as “the Browndale cottages”, after the private centres for disturbed children being run by Warrendale’s founder, John Brown. These cottages are located just south of the main building.

East of the main building was Etobicoke-Humber School. This school was part of the Toronto District School Board system and served students who required that their educational needs be met outside of the regular school system. With highly trained staff who worked with up to 35 different outside agencies, programs were designed to meet the unique needs of students from four to nineteen years of age.

Thistletown Regional Centre’s buildings are still standing on 36 acres of land in a park-like setting. The 50,000 seedlings planted in 1926 make this a beautiful place for a walk, and there are public walking paths through the grounds and by the Humber River. However, things have changed, and now care for these children is offered in the community. The hospital closed in 2014, and the property was declared surplus by the Provincial Government and is for sale. Its future is still unknown.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Drive south, behind the main building, to see the ten cottages. Then turn around and drive back towards Panorama Court. As you pass the main building, note the screened porches on the south side of the building, built when the facility was used by Sick Children’s Hospital. Return to Panorama Court and drive west. On your left, you will pass the former Father Henry Carr Catholic Secondary School, formed in 1974 by the Basilian Fathers and named for the founder of St. Michael’s College at the University of Toronto. In 2007, the school moved to a larger location on Martin Grove Road at Finch Avenue West. As part of a City of Toronto plan to improve the community infrastructure of the designated Jamestown Priority Neighbourhood, this 5800 square metre former school building has been turned into the Rexdale Multi-Service Community Hub. It includes a health centre, a legal clinic, a woman’s centre, a skills development agency, a shared gymnasium, and other community services for the area. Drive to Kipling Avenue and turn right. Drive north and turn right at the next street, Rowntree Road. Turn left into the parking lot of North Kipling Junior Middle School and STOP

As you read in Tour I about Warrendale, by the mid-1960s, a major learning for many in child psychiatry was the revelation that experiencing a group living situation can be healing to a child who previously had never lived in a “normal” family environment. In 1972, Thistletown Centre constructed ten small houses on the property, modelled on Warrendale, and moved most of the children out of a “hospital” setting into these cottages where they could experience living in family-style groups. The staff here referred to these homes, unofficially, as “the Browndale cottages”, after the private centres for disturbed children being run by Warrendale’s founder, John Brown. These cottages are located just south of the main building.

East of the main building was Etobicoke-Humber School. This school was part of the Toronto District School Board system and served students who required that their educational needs be met outside of the regular school system. With highly trained staff who worked with up to 35 different outside agencies, programs were designed to meet the unique needs of students from four to nineteen years of age.

Thistletown Regional Centre’s buildings are still standing on 36 acres of land in a park-like setting. The 50,000 seedlings planted in 1926 make this a beautiful place for a walk, and there are public walking paths through the grounds and by the Humber River. However, things have changed, and now care for these children is offered in the community. The hospital closed in 2014, and the property was declared surplus by the Provincial Government and is for sale. Its future is still unknown.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Drive south, behind the main building, to see the ten cottages. Then turn around and drive back towards Panorama Court. As you pass the main building, note the screened porches on the south side of the building, built when the facility was used by Sick Children’s Hospital. Return to Panorama Court and drive west. On your left, you will pass the former Father Henry Carr Catholic Secondary School, formed in 1974 by the Basilian Fathers and named for the founder of St. Michael’s College at the University of Toronto. In 2007, the school moved to a larger location on Martin Grove Road at Finch Avenue West. As part of a City of Toronto plan to improve the community infrastructure of the designated Jamestown Priority Neighbourhood, this 5800 square metre former school building has been turned into the Rexdale Multi-Service Community Hub. It includes a health centre, a legal clinic, a woman’s centre, a skills development agency, a shared gymnasium, and other community services for the area. Drive to Kipling Avenue and turn right. Drive north and turn right at the next street, Rowntree Road. Turn left into the parking lot of North Kipling Junior Middle School and STOP

Stop Twelve (Map G): North Kipling and Rowntree Road

The story of Rowntree Road began in 1843 when John Rowntree purchased 13 hectares here, between the Humber River and Kipling Avenue, later selling the lot to his son, Joseph for £5. By 1848, Joseph had also bought two large lots on the east bank of the river in York Township. He built a sawmill on the east bank and a grist mill on the west bank. Although Joseph and his family originally lived in a log cabin, by 1851 they had built a large storey-and-a-half red and buff brick home half way up the river valley side, just north of the grist mill. Rowntree called his home and mill complex Greenholme Mills. In the mid-1850s, he built a rough road along the route of today’s Rowntree Road from Kipling Avenue, down a steep path into the valley, across the Humber River on a bridge just south of the mills, and up the other side to Islington Avenue. The mills operated into the early 20th century and the house stood until the late 1950s.

By the 1950s, there was a summer resort called Riverbank Park on the east side of the Humber River, with cottages lining the river bank. In 1954, Hurricane Hazel swept away 12 of the cottages and changed the river’s contours considerably. By 1959, the area had been made into 103-hectare Rowntree Mills Park, with an entrance off Islington Avenue. By 1960, the car bridge over the Humber River had been replaced by a pedestrian bridge.

Toronto is home to the second largest concentration of high-rise buildings in North America with almost 1000 towers built on the “tower in the park” model where each tower is surrounded by large amounts of green space, usually in the suburbs on former farmers’ fields. Most of these buildings were put up in the late 1960s/early 1970s, are aging, and are in serious need of upgrade.

On Kipling, north of Finch, there are 18 apartment towers along the Humber Valley, housing over 13,000 people. This is roughly the same population as the downtown neighbourhood of the Annex, or the Ontario municipality of Port Hope. Ten towers are rental apartments that are showing their age, but five at north end and three on the east side of Rowntree Road overlooking valley are 1980s condominiums and are in significantly better shape. Open space around these buildings is 90% of the total area, yet so little of it is used that the area looks abandoned despite a high population density of 354 people per hectare, one of highest in Toronto. The rental apartment buildings were originally designed for young couples and singles, with few facilities for children, but the buildings are now being used almost exclusively by families, 40% of whom are recent immigrants.

Twenty-five percent of the area’s population are children aged one to fourteen, compared to a city average of 16%. Eighty-six percent are visible minorities, compared to 8% in the whole city. The area’s average annual income is half that of the city average. Many speak little or no English, and are “stranded”, both physically & culturally: they have to drive or take a bus for simple errands or social contact, and many don’t own cars.

The City of Toronto has plans underway to renew these towers, not only by upgrading the buildings, but also to turn them into sustainable green communities with innovations such as: green roofs; solar, wind and geothermal energy; water conservation methodologies; on-site waste management; community gardens; and small retail markets catering to the different ethnic groups.

Toronto is home to the second largest concentration of high-rise buildings in North America with almost 1000 towers built on the “tower in the park” model where each tower is surrounded by large amounts of green space, usually in the suburbs on former farmers’ fields. Most of these buildings were put up in the late 1960s/early 1970s, are aging, and are in serious need of upgrade.

On Kipling, north of Finch, there are 18 apartment towers along the Humber Valley, housing over 13,000 people. This is roughly the same population as the downtown neighbourhood of the Annex, or the Ontario municipality of Port Hope. Ten towers are rental apartments that are showing their age, but five at north end and three on the east side of Rowntree Road overlooking valley are 1980s condominiums and are in significantly better shape. Open space around these buildings is 90% of the total area, yet so little of it is used that the area looks abandoned despite a high population density of 354 people per hectare, one of highest in Toronto. The rental apartment buildings were originally designed for young couples and singles, with few facilities for children, but the buildings are now being used almost exclusively by families, 40% of whom are recent immigrants.

Twenty-five percent of the area’s population are children aged one to fourteen, compared to a city average of 16%. Eighty-six percent are visible minorities, compared to 8% in the whole city. The area’s average annual income is half that of the city average. Many speak little or no English, and are “stranded”, both physically & culturally: they have to drive or take a bus for simple errands or social contact, and many don’t own cars.

The City of Toronto has plans underway to renew these towers, not only by upgrading the buildings, but also to turn them into sustainable green communities with innovations such as: green roofs; solar, wind and geothermal energy; water conservation methodologies; on-site waste management; community gardens; and small retail markets catering to the different ethnic groups.

Google Earth view of North Kipling area, with northeast at the top. Kipling Av. passes diagonally across this view from bottom right to top left. North Kipling Junior-Middle School and a small shopping plaza in the centre on opposite sides of Rowntree Road. The other 18 tall buildings (see their shadows above) are apartment or condominium towers.