Claireville

Until the late 1980s, Codlin Crescent in the northwest corner of Etobicoke was called Albion Road and was the peaceful, tree-lined main street of the 19th century village of Claireville. This village overlapped three townships - Etobicoke, Vaughan and Toronto Gore - and surrounded the intersection of Indian Line/Highway 50, Steeles Avenue and Albion Road. The village started as a crossroads service centre for the surrounding farming community. In 1832, John Dark’s Halfway House opened on the southwest corner of Steeles and Indian Line. The “Humber” post office opened in Bowman’s General Store in 1842.

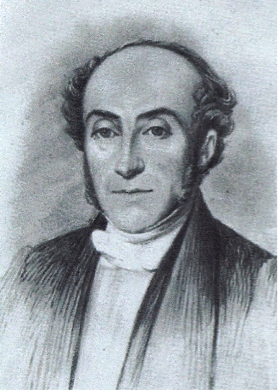

The “Father” of Claireville is considered to have been Jean du Petit Pont de la Haye. Born in France in 1799, he was unhappy with France’s politics. He moved to Britain to teach in 1828, and while there met the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, Sir John Colborne, who asked him to be the French Master of the new Upper Canada College (UCC) opening in 1829 in York. De la Haye said, “Yes!” and taught French at UCC for 27 years. Although he lived with his family on the UCC campus when school was in session, in 1840 he built a country home called Les Ormes (The Elms), west of Indian Line, south of Steeles, in Toronto Gore Township. At the same time, he purchased 40 hectare Lot 40, Concession 4, in the very northwest corner of Etobicoke. In 1851 he registered a plan for a town there to be called Claireville, named for the eldest of his six daughters, Claire. Alcide Street was named after his son, who became a physician in Toronto. Pauline Street (now gone) was named for another daughter.

The “Father” of Claireville is considered to have been Jean du Petit Pont de la Haye. Born in France in 1799, he was unhappy with France’s politics. He moved to Britain to teach in 1828, and while there met the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, Sir John Colborne, who asked him to be the French Master of the new Upper Canada College (UCC) opening in 1829 in York. De la Haye said, “Yes!” and taught French at UCC for 27 years. Although he lived with his family on the UCC campus when school was in session, in 1840 he built a country home called Les Ormes (The Elms), west of Indian Line, south of Steeles, in Toronto Gore Township. At the same time, he purchased 40 hectare Lot 40, Concession 4, in the very northwest corner of Etobicoke. In 1851 he registered a plan for a town there to be called Claireville, named for the eldest of his six daughters, Claire. Alcide Street was named after his son, who became a physician in Toronto. Pauline Street (now gone) was named for another daughter.

A generous, egalitarian man, de la Haye donated church sites in Claireville to three different church denominations: Congregationalists in 1842, Primitive Methodists in 1846, and Roman Catholics in 1860. He was a director and majority shareholder of the Albion Plank Road Company, incorporated in 1846 to build an improved road from Thistletown, through Claireville, and west into Peel County. After de la Haye retired, he became a local justice of the peace and a member of the Toronto Gore Township Council.

By 1870 the population of Claireville was 175, and the village had two hotels, two general stores, one butcher, one blacksmith, one tailor, one cabinet maker, a toll gate, and a steam-operated flour mill.

In 1842, a Congregational Church opened on Albion Road. The church was sold to the Anglican Church in 1897, who replaced it with a beautiful Gothic bi-colour brick building with a bi-colour slate roof. After the congregation disbanded ca. 1934, the church was converted to a home for Edward and Ella Perry, who operated an apiary there until 1959. Its demolition date is unknown.

By 1870 the population of Claireville was 175, and the village had two hotels, two general stores, one butcher, one blacksmith, one tailor, one cabinet maker, a toll gate, and a steam-operated flour mill.

In 1842, a Congregational Church opened on Albion Road. The church was sold to the Anglican Church in 1897, who replaced it with a beautiful Gothic bi-colour brick building with a bi-colour slate roof. After the congregation disbanded ca. 1934, the church was converted to a home for Edward and Ella Perry, who operated an apiary there until 1959. Its demolition date is unknown.

In 1846, a Primitive Methodist Chapel of white clapboard with three tall windows on each side wall was built on the south side of Steeles Avenue West. In the 1880s, it became a gospel hall for a group of Evangelists. It was demolished in the 1990s.

Things began to change in the early 1900s as the automobile grew in popularity. At that time, Lake Shore Bl. W. was lined on both sides with houses. By the 1920s, some residents had added tourist services to their properties, including campgrounds, cabins, restaurants, and gas filling stations. It all began when some American tourists asked the Hicks family if they could erect a tent near their hotel. The Hicks then opened their “Humber Bay Tourist Camp” on the beach side of Lake Shore Bl. W. Other residents soon followed suit. Just east of John Duck’s hotel was the fenced-in Edgecliffe Beach, owned by Emil Brooker. He also opened the Rendezvous Dance Hall, the Edgecliffe Tea Room, and the area’s first drive-in restaurant, Brooker’s Barbecue.

From the 1920s to the 1980s, the Kitchener family played a major role in the life of the village. In 1923, Albert and Gertrude Kitchener bought the property at 2152 Albion Road (now Codlin Crescent.) Albert and his son Charlie built a new house on that property in 1941, and Charlie lived there until 1979. Eventually family members lived on five properties, three with houses built by Albert himself. Albert built another house and a service station west of his own house for his son Lorne, who operated a Supertest franchise there until 1980. William and Jessie Kitchener bought the house at 2119 Albion Road in 1920. In 1935, it was inherited by their son Everton Kitchener who owned a threshing machine that he rented to local farmers during harvest season. Everton lived there until his death in 1981. Percy Kitchener lived in a house immediately west of Everton’s. On the west side of Indian Line at Albion Road, Albert built another house where his grandson Grant grew up. .

Claireville continued its role as a farming service centre until after World War II. Along with the post-war baby boom, farming as a career was slowly being replaced by more lucrative jobs in industry and offices. In this changing environment, by the late 1980s there were major plans to reconfigure roads in the area to accommodate the new Highways 427 and 407. This resulted in the expropriation and demolition of many buildings in old Claireville. All buildings along Indian Line and Steeles were demolished, as were the homes of Lorne, Percy and Glenn Kitchener, the general store, and Lorne Kitchener’s service station. By-passes of Albion Road and Steeles Avenue West were built around Claireville, while Indian Line was completely obliterated. What had originally been Albion and Steeles within the village were then joined at their western ends to form a horseshoe-shaped street named Codlin Crescent after a local pioneering family. At the same time, Pauline Street, William Street, and part of Alcide Street were permanently closed.

As farms disappeared, Etobicoke Council rezoned most of the land surrounding Claireville to be Employment/ Industrial. When houses along Codlin Crescent came up for sale, they were bought for uses that were inconsistent with residential by-laws, e.g. a truck driving school, a tractor/trailer parking lot, a construction company, religious institutions, etc. In 2000, the City of Toronto “fixed” this zoning discrepancy by passing a by-law that grandfathered approval of all existing business uses in the village. With only 14 buildings from the old village remaining and only a couple of them still lived in, Claireville is literally a ghost of its former self, yet is alive when looked at in the context of its new roles.

It seems inevitable that one day, an application will be filed to demolish all of Claireville’s remaining buildings and redevelop the land. If this happens, there is one building at 2095 Codling Crescent that should be preserved. This is the oldest building remaining in Claireville, built in 1851, and the only property that is listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register. It has a secret past that was only recently confirmed. Claireville’s first tollgate in 1846 was located on Highway 50, north of Steeles Avenue West. However, by 1871, the tollgate was located at 2095 Codlin Crescent (originally 2095 Albion Road.) Christopher Armstrong was the tollkeeper, and he lived in the house with his family. That makes this building one of only two former toll houses known to exist in City of Toronto and the only one in its original location. Now owned by a tractor/trailer storage company, it looks shabby and unloved, but its history is impressive.

As farms disappeared, Etobicoke Council rezoned most of the land surrounding Claireville to be Employment/ Industrial. When houses along Codlin Crescent came up for sale, they were bought for uses that were inconsistent with residential by-laws, e.g. a truck driving school, a tractor/trailer parking lot, a construction company, religious institutions, etc. In 2000, the City of Toronto “fixed” this zoning discrepancy by passing a by-law that grandfathered approval of all existing business uses in the village. With only 14 buildings from the old village remaining and only a couple of them still lived in, Claireville is literally a ghost of its former self, yet is alive when looked at in the context of its new roles.

It seems inevitable that one day, an application will be filed to demolish all of Claireville’s remaining buildings and redevelop the land. If this happens, there is one building at 2095 Codling Crescent that should be preserved. This is the oldest building remaining in Claireville, built in 1851, and the only property that is listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register. It has a secret past that was only recently confirmed. Claireville’s first tollgate in 1846 was located on Highway 50, north of Steeles Avenue West. However, by 1871, the tollgate was located at 2095 Codlin Crescent (originally 2095 Albion Road.) Christopher Armstrong was the tollkeeper, and he lived in the house with his family. That makes this building one of only two former toll houses known to exist in City of Toronto and the only one in its original location. Now owned by a tractor/trailer storage company, it looks shabby and unloved, but its history is impressive.

Researched and Written by Denise Harris