Hurricane Hazel

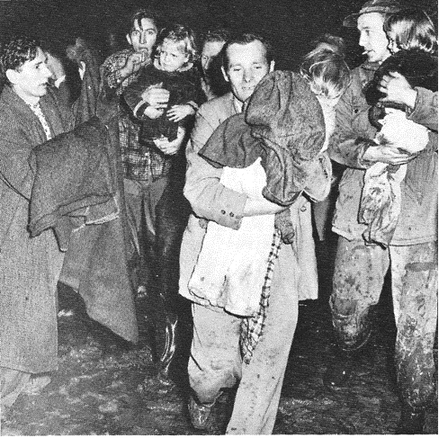

This photo shows Richard Yorke’s rescue party and members of the rescued White family after they were brought to safety. Richard is 2nd from left (only the back of his head is visible); John Elsen is 3rd from left and “Big Red” is 5th from left and partially hidden. The three sisters being held are, from left to right, Linda White (age 5), Debbie (3) and Peggy (4).

PART 1: THE ADVENTURE OF A LIFETIME

In many past recollections of Hurricane Hazel, much has been written, and rightfully so, of the terrifying events along the course of the Humber River, but little has been written about the events that evening along the Etobicoke Creek.

Having lived all my youthful life up to the age of 18 in Long Branch, the creek was always a source of great adventure. In the spring, the annual flood would come sometime in March, usually caused by a large ice jam in a 90 degree bend in the river near where it ran into Lake Ontario. The grim announcement was solemnly read at school that all students living down in the river flats should leave for home immediately as the river was beginning to rise. This always puzzled me because one would think they would be better off and safer staying at school.

After the floods subsided, the suckers (fish) would run and could be regularly netted anywhere along the banks. Why I don’t know, because they were terribly boney fish! I personally preferred hiking up the creek, with a gang of friends, complete with knapsack and water bottle – World War II issue – with one’s imagination running rampant, inventing adventures and excitement, returning home late in the day, soaked and covered in mud. As very young lads, we used to follow the soldiers taking their training at Long Branch Army Camp, up the creek and through the great obstacle course. In the summer, it was peaceful and warm and great for swimming.

Then suddenly one October night in 1954 began one of our greatest adventures on the creek. I was 18 and an apprentice electrician still living in Long Branch with a school chum, Jim Borland, and his family, since mine had moved away to a farm near Alliston. I had borrowed a car for the weekend from a friend of mine and was having great fun cruising in the now-driving rain through giant pools and flooded roads.

I had dropped my girlfriend off at about 10:00 pm that night and headed back to Borlands’ where I received a distress call from a friend in Lakeview, west of Etobicoke, whose car wouldn’t start because of the wet. I drove out immediately, crossing the creek via Lakeshore Road as it was then called, pushed my friend’s car and got him started, and then headed home again.

This time, as I approached the bridge, coming from the west, I could see a gathering of fire engines, ambulances, tow-trucks and people running desperately in all directions. I stopped and rolled down the window for a better look and it was truly frightening. The creek was now a massive roaring torrent, carrying everything imaginable with it. Whole trees, large pieces of houses, and every now and then a complete house trailer, from a trailer camp on the north side of the highway, would catapult out from under the bridge with such tremendous force, it would actually become airborne for a few short seconds before disappearing into the dark, driven by this awesome mass of raging water.

A flood in the fall!! This wasn’t possible, but by God there it was, not like the annual spring flood we used to watch with great interest every year. This was indeed a monster.

I drove home to Borlands’ as quickly as possible and ran into the house to tell what I had seen and found everyone gathered in the kitchen listening to urgent radio reports of flooding rivers and streams all over Southern Ontario, the worst being the Humber River. There was a desperate plea for volunteers and equipment, especially boats, to report to the disaster areas.

Just then a friend of the family appeared at the door in tears, telling us her family was trapped in the flood in their home on Island Road by the Etobicoke River and could we help.

In a small convoy we moved from the house to the river, which was raging worse than before. We milled about with the rest of the disorganized crowd, some trying to help, some just curiosity seekers.

By now there were five of us prepared to go in and help: John Elsen, a fellow electrician, originally from Holland, Jim Borland, Keith Coulter, Bob Keene and myself - all school buddies. The roar of the river was loud; you could hardly hear yourself think. The water was pushing out from under the bridge completely filling the viaduct. The fire engine from the Long Branch volunteer fire brigade was parked on the slope down to Island Road with all of its big floodlights on to aid the rescuers.

A man approached us shouting he had a boat for anyone interested. The five of us looked at one another as if to say, “This is it”, and went back to the highway with the man and removed his boat, a sleek-looking homemade speed boat, from its trailer and carried it to the water’s edge and launched it. We were all set, but where and how did we go about this incredible task?

Just then a large red headed man, absolutely soaked and stripped to the waist, stepped in front of our boat and said, “Where in the hell do you think you’re going?” We explained we wanted to go in and help with the rescue, whereupon he proceeded to give us a lecture on how inexperienced we were and how near impossible it was to get through, but if we were dumb enough to want to go, he would lead us through and that there was no other way but that he was in charge. That was fine with us because he sure looked capable enough, something like your typical loud and mean Sergeant Major. We nicknamed him appropriately “Big Red” and took all orders without question from him.

Away we went, aligning ourselves on both sides of the boat. He put me at the bow, pulling on the rope and giving instructions to go either left or right. We headed straight down Island Road into the rapidly flowing, ever deepening water, for about half a block, and then Big Red shouted the order, “Cut to your right boys, between the houses.” This we did obediently. The water was getting deeper and deeper until finally everyone was hanging desperately to the sides of the boat and I to the rope, literally swimming and pulling the boat.

We arrived at the friend’s family’s house just in time to see them rescued by someone who had driven a big truck down Island Road. We continued south towards Lake Ontario to help any others who might be in trouble.

We were now out of the friendly spotlight of the fire truck. As we passed between the houses into what would be backyards, I recall getting my feet caught in what must have been a fence and the boat bearing down on me, pushing me right under. Fortunately, my feet came free and I popped back up only to hear Big Red say, “Can’t you steer the god dammed boat?” and I sputtered, “I sure can, when I’m on top of the water.” The water got a little shallower and we were walking again. We now had an opportunity to see the mess through which we were making our way: houses literally lifted from their foundations were lying askew, some missing completely, overturned cars and trucks, and the army of volunteers with their boats picking up families waiting on rooftops of houses and garages, some people up in trees, dogs barking and swimming around in the mess.

I recall vividly passing by a house and hearing a terrible crack, and looking around and seeing the place literally falling to pieces before our very eyes. Fortunately, it was empty.

We pushed on until we came to an impasse where the water roared through like the whole river had cut a new path for itself. How do we possibly get through this? Ahead of us was a boatload of firemen pondering the situation. Across the raging torrent was a man standing on the front porch of his house. One of the firemen threw a rope, Lone Ranger-style, right to the porch of the house. The man grabbed it and immediately tied it to a post on the house and the fireman tied his end tightly to a tree.

The firemen lay along the sides of the gunwales of their boat, all holding the rope, and pulled themselves across. Big Red gave us orders to do exactly the same, which we did. What a relief to get out of that cold water, but were we going to make it across, or end up in the middle of Lake Ontario? When you took hold of that rope, nothing was going to break your grip, no matter how much the boat tossed and pitched.

Once across, Big Red ordered us out of the boat and back into that cold, dirty, stinking water - oh boy! Most of us had learned to swim in cold Lake Ontario, but that was in the summer; this was something else.

On we plodded or swam through muck and debris-filled water. Suddenly a man called from a house that they had four children and could we please help. We pulled our boat over to the front porch of the house and the four children were immediately bundled into the boat, then the parents. As we pulled away, the house began to collapse and float away.

I took a quick look around and there they were - the shivering groups huddled on rooftops and up in the large willow trees, which still stand in what is now Marie Curtis Park. One man I could see up in the tree had beside him a pair of crutches. They called to us for help!

The feeling of adventure had now turned to a feeling of despair. We had a boat full already, possibly more than we could handle on the dangerous trip back. There was no way we could take more without endangering those we already had in our charge.

Voices shouting in the distance, more rescuers and boats coming through, thank God. We shouted encouragement to the stranded and started the long trip back.

The eastern sky was showing signs of the first glow of dawn and the water was showing signs of receding. When we arrived at the point we were all dreading, where we had pulled ourselves and the boat across by rope, the water was down sufficiently that we were able to wade across without too much difficulty. The water was fast receding and soon we were in sight of Lakeshore Road. The sun was now up and sure felt good, and the last block we pushed the boat through knee-deep mud. Dry land at last, the children and parents bundled off to waiting arms of friends, after saying their grateful thanks.

We stood there, dazed and shivering, surveying the desolation, then departed to a hot bath and breakfast.

This first part of the article was written by Richard Yorke. He never heard the names of the family members he had helped rescue. He worked as an electrician for 35 years before retiring to Vancouver Island where he joined the Coast Guard Auxiliary and crewed on a marine rescue boat for 14 years. He returned to Etobicoke to be closer to family and where he is an avid gardener, astronomer and musician, playing the euphonium in a concert band. This is the first time his gripping story about Hurricane Hazel has been published.

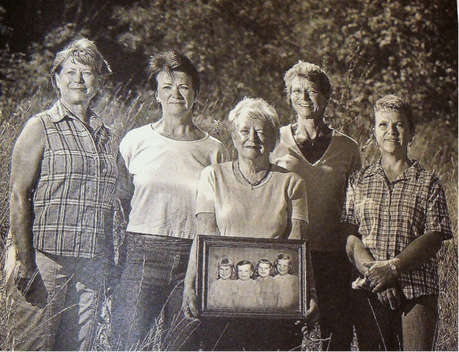

The photo at the beginning of the article appeared in the Toronto Star on October 16,1954, however Yorke didn’t see it until 2017.

In 2004, the Toronto Star published 50th anniversary stories about Hurricane Hazel. What follows is the story of that evening related by Laura White to reporter, Maureen Murray, in 2004.

In many past recollections of Hurricane Hazel, much has been written, and rightfully so, of the terrifying events along the course of the Humber River, but little has been written about the events that evening along the Etobicoke Creek.

Having lived all my youthful life up to the age of 18 in Long Branch, the creek was always a source of great adventure. In the spring, the annual flood would come sometime in March, usually caused by a large ice jam in a 90 degree bend in the river near where it ran into Lake Ontario. The grim announcement was solemnly read at school that all students living down in the river flats should leave for home immediately as the river was beginning to rise. This always puzzled me because one would think they would be better off and safer staying at school.

After the floods subsided, the suckers (fish) would run and could be regularly netted anywhere along the banks. Why I don’t know, because they were terribly boney fish! I personally preferred hiking up the creek, with a gang of friends, complete with knapsack and water bottle – World War II issue – with one’s imagination running rampant, inventing adventures and excitement, returning home late in the day, soaked and covered in mud. As very young lads, we used to follow the soldiers taking their training at Long Branch Army Camp, up the creek and through the great obstacle course. In the summer, it was peaceful and warm and great for swimming.

Then suddenly one October night in 1954 began one of our greatest adventures on the creek. I was 18 and an apprentice electrician still living in Long Branch with a school chum, Jim Borland, and his family, since mine had moved away to a farm near Alliston. I had borrowed a car for the weekend from a friend of mine and was having great fun cruising in the now-driving rain through giant pools and flooded roads.

I had dropped my girlfriend off at about 10:00 pm that night and headed back to Borlands’ where I received a distress call from a friend in Lakeview, west of Etobicoke, whose car wouldn’t start because of the wet. I drove out immediately, crossing the creek via Lakeshore Road as it was then called, pushed my friend’s car and got him started, and then headed home again.

This time, as I approached the bridge, coming from the west, I could see a gathering of fire engines, ambulances, tow-trucks and people running desperately in all directions. I stopped and rolled down the window for a better look and it was truly frightening. The creek was now a massive roaring torrent, carrying everything imaginable with it. Whole trees, large pieces of houses, and every now and then a complete house trailer, from a trailer camp on the north side of the highway, would catapult out from under the bridge with such tremendous force, it would actually become airborne for a few short seconds before disappearing into the dark, driven by this awesome mass of raging water.

A flood in the fall!! This wasn’t possible, but by God there it was, not like the annual spring flood we used to watch with great interest every year. This was indeed a monster.

I drove home to Borlands’ as quickly as possible and ran into the house to tell what I had seen and found everyone gathered in the kitchen listening to urgent radio reports of flooding rivers and streams all over Southern Ontario, the worst being the Humber River. There was a desperate plea for volunteers and equipment, especially boats, to report to the disaster areas.

Just then a friend of the family appeared at the door in tears, telling us her family was trapped in the flood in their home on Island Road by the Etobicoke River and could we help.

In a small convoy we moved from the house to the river, which was raging worse than before. We milled about with the rest of the disorganized crowd, some trying to help, some just curiosity seekers.

By now there were five of us prepared to go in and help: John Elsen, a fellow electrician, originally from Holland, Jim Borland, Keith Coulter, Bob Keene and myself - all school buddies. The roar of the river was loud; you could hardly hear yourself think. The water was pushing out from under the bridge completely filling the viaduct. The fire engine from the Long Branch volunteer fire brigade was parked on the slope down to Island Road with all of its big floodlights on to aid the rescuers.

A man approached us shouting he had a boat for anyone interested. The five of us looked at one another as if to say, “This is it”, and went back to the highway with the man and removed his boat, a sleek-looking homemade speed boat, from its trailer and carried it to the water’s edge and launched it. We were all set, but where and how did we go about this incredible task?

Just then a large red headed man, absolutely soaked and stripped to the waist, stepped in front of our boat and said, “Where in the hell do you think you’re going?” We explained we wanted to go in and help with the rescue, whereupon he proceeded to give us a lecture on how inexperienced we were and how near impossible it was to get through, but if we were dumb enough to want to go, he would lead us through and that there was no other way but that he was in charge. That was fine with us because he sure looked capable enough, something like your typical loud and mean Sergeant Major. We nicknamed him appropriately “Big Red” and took all orders without question from him.

Away we went, aligning ourselves on both sides of the boat. He put me at the bow, pulling on the rope and giving instructions to go either left or right. We headed straight down Island Road into the rapidly flowing, ever deepening water, for about half a block, and then Big Red shouted the order, “Cut to your right boys, between the houses.” This we did obediently. The water was getting deeper and deeper until finally everyone was hanging desperately to the sides of the boat and I to the rope, literally swimming and pulling the boat.

We arrived at the friend’s family’s house just in time to see them rescued by someone who had driven a big truck down Island Road. We continued south towards Lake Ontario to help any others who might be in trouble.

We were now out of the friendly spotlight of the fire truck. As we passed between the houses into what would be backyards, I recall getting my feet caught in what must have been a fence and the boat bearing down on me, pushing me right under. Fortunately, my feet came free and I popped back up only to hear Big Red say, “Can’t you steer the god dammed boat?” and I sputtered, “I sure can, when I’m on top of the water.” The water got a little shallower and we were walking again. We now had an opportunity to see the mess through which we were making our way: houses literally lifted from their foundations were lying askew, some missing completely, overturned cars and trucks, and the army of volunteers with their boats picking up families waiting on rooftops of houses and garages, some people up in trees, dogs barking and swimming around in the mess.

I recall vividly passing by a house and hearing a terrible crack, and looking around and seeing the place literally falling to pieces before our very eyes. Fortunately, it was empty.

We pushed on until we came to an impasse where the water roared through like the whole river had cut a new path for itself. How do we possibly get through this? Ahead of us was a boatload of firemen pondering the situation. Across the raging torrent was a man standing on the front porch of his house. One of the firemen threw a rope, Lone Ranger-style, right to the porch of the house. The man grabbed it and immediately tied it to a post on the house and the fireman tied his end tightly to a tree.

The firemen lay along the sides of the gunwales of their boat, all holding the rope, and pulled themselves across. Big Red gave us orders to do exactly the same, which we did. What a relief to get out of that cold water, but were we going to make it across, or end up in the middle of Lake Ontario? When you took hold of that rope, nothing was going to break your grip, no matter how much the boat tossed and pitched.

Once across, Big Red ordered us out of the boat and back into that cold, dirty, stinking water - oh boy! Most of us had learned to swim in cold Lake Ontario, but that was in the summer; this was something else.

On we plodded or swam through muck and debris-filled water. Suddenly a man called from a house that they had four children and could we please help. We pulled our boat over to the front porch of the house and the four children were immediately bundled into the boat, then the parents. As we pulled away, the house began to collapse and float away.

I took a quick look around and there they were - the shivering groups huddled on rooftops and up in the large willow trees, which still stand in what is now Marie Curtis Park. One man I could see up in the tree had beside him a pair of crutches. They called to us for help!

The feeling of adventure had now turned to a feeling of despair. We had a boat full already, possibly more than we could handle on the dangerous trip back. There was no way we could take more without endangering those we already had in our charge.

Voices shouting in the distance, more rescuers and boats coming through, thank God. We shouted encouragement to the stranded and started the long trip back.

The eastern sky was showing signs of the first glow of dawn and the water was showing signs of receding. When we arrived at the point we were all dreading, where we had pulled ourselves and the boat across by rope, the water was down sufficiently that we were able to wade across without too much difficulty. The water was fast receding and soon we were in sight of Lakeshore Road. The sun was now up and sure felt good, and the last block we pushed the boat through knee-deep mud. Dry land at last, the children and parents bundled off to waiting arms of friends, after saying their grateful thanks.

We stood there, dazed and shivering, surveying the desolation, then departed to a hot bath and breakfast.

This first part of the article was written by Richard Yorke. He never heard the names of the family members he had helped rescue. He worked as an electrician for 35 years before retiring to Vancouver Island where he joined the Coast Guard Auxiliary and crewed on a marine rescue boat for 14 years. He returned to Etobicoke to be closer to family and where he is an avid gardener, astronomer and musician, playing the euphonium in a concert band. This is the first time his gripping story about Hurricane Hazel has been published.

The photo at the beginning of the article appeared in the Toronto Star on October 16,1954, however Yorke didn’t see it until 2017.

In 2004, the Toronto Star published 50th anniversary stories about Hurricane Hazel. What follows is the story of that evening related by Laura White to reporter, Maureen Murray, in 2004.

PART II: THE TERROR OF A LIFETIME

White remembers all too clearly the night when gentle Etobicoke Creek turned into a killer. The flood waters which quickly accumulated after the tail end of Hurricane Hazel lashed southern Ontario on the night of October 15, 1954, caught just about everyone by surprise.

Residents like Laura White, who lived in modest bungalows and trailers dotted alongside river beds on the edge of Toronto, were perhaps the most unaware that their lives were about to be swept away by an unstoppable wall of water.

“We thought it was just a bit of rain and flooding of the river bed,” say White, who lived on Island Road, a deadend street that hugged Etobicoke Creek in the community of Long Branch.

White, then a young mother of four daughters under 6, first suspected something was very wrong when she ran across the street to her neighbours, the Thorpes, to use their phone to call her mother-in-law.

“We were poor little mice. We had no phone so I went over to the Thorpes to use theirs. By the time I was heading back, the water had risen to just below my knees and there was a swift current.”

White suggested that Patricia Thorpe grab her two-year-old son and 4-month-old daughter and come back across the street to her house because it was further from the banks of the creek. “She didn’t seem to be concerned at all. She kept saying, ‘We’ll be all right.’”

By morning, the Thorpes’ home had been washed away and every member of the family had drowned except for the infant Nancy, who was passed to a firefighter by her mother at the last minute.

“For years I was haunted about it,” White says, “If they had just come over they might have been all right. All the houses on Island Rd. were pretty ramshackle. They weren’t built to stand up to the flood.”

“We sat up at a neighbour’s house playing cards because we didn’t want to go to bed. Our little children were asleep. All of a sudden water rushed into the house and, within minutes, we were up to our waists in water.”

White remembers all too clearly the night when gentle Etobicoke Creek turned into a killer. The flood waters which quickly accumulated after the tail end of Hurricane Hazel lashed southern Ontario on the night of October 15, 1954, caught just about everyone by surprise.

Residents like Laura White, who lived in modest bungalows and trailers dotted alongside river beds on the edge of Toronto, were perhaps the most unaware that their lives were about to be swept away by an unstoppable wall of water.

“We thought it was just a bit of rain and flooding of the river bed,” say White, who lived on Island Road, a deadend street that hugged Etobicoke Creek in the community of Long Branch.

White, then a young mother of four daughters under 6, first suspected something was very wrong when she ran across the street to her neighbours, the Thorpes, to use their phone to call her mother-in-law.

“We were poor little mice. We had no phone so I went over to the Thorpes to use theirs. By the time I was heading back, the water had risen to just below my knees and there was a swift current.”

White suggested that Patricia Thorpe grab her two-year-old son and 4-month-old daughter and come back across the street to her house because it was further from the banks of the creek. “She didn’t seem to be concerned at all. She kept saying, ‘We’ll be all right.’”

By morning, the Thorpes’ home had been washed away and every member of the family had drowned except for the infant Nancy, who was passed to a firefighter by her mother at the last minute.

“For years I was haunted about it,” White says, “If they had just come over they might have been all right. All the houses on Island Rd. were pretty ramshackle. They weren’t built to stand up to the flood.”

“We sat up at a neighbour’s house playing cards because we didn’t want to go to bed. Our little children were asleep. All of a sudden water rushed into the house and, within minutes, we were up to our waists in water.”

White, her husband Russell, their four children ages 2, 3, 4 and 5, and two adult neighbours managed to climb into the crawl space of an unfinished attic and spent the night perched on a two-by-four as they watched the water steadily rise beneath them.

“We watched as the water reached the top of the fridge. It got to at least 10 feet high. At one point my husband punched a hole in the roof because we thought we might have to climb out and sit up there. The house started to move. It must have moved a few feet, but was stopped when it hit some trees.”

Luckily, around 5 a.m. the next morning, White and her family were rescued by volunteers in a motor boat.

“For a few months, or even years, I had nightmares about what would have happened if we had been flung into the water,” says White, who lives today in a Brampton condominium.

“It was really surreal. It was a freaky thing.” says White, who went on to have a total of eight children and today at 73, has 15 grandchildren and 16 great-grandchildren.

She has never been quite the same since that fateful fall day 50 years ago when Etobicoke Creek roared: “I never wanted to live near water again.”

From an article by staff reporter Maureen Murray in the Toronto Star, October 2, 2004

“We watched as the water reached the top of the fridge. It got to at least 10 feet high. At one point my husband punched a hole in the roof because we thought we might have to climb out and sit up there. The house started to move. It must have moved a few feet, but was stopped when it hit some trees.”

Luckily, around 5 a.m. the next morning, White and her family were rescued by volunteers in a motor boat.

“For a few months, or even years, I had nightmares about what would have happened if we had been flung into the water,” says White, who lives today in a Brampton condominium.

“It was really surreal. It was a freaky thing.” says White, who went on to have a total of eight children and today at 73, has 15 grandchildren and 16 great-grandchildren.

She has never been quite the same since that fateful fall day 50 years ago when Etobicoke Creek roared: “I never wanted to live near water again.”

From an article by staff reporter Maureen Murray in the Toronto Star, October 2, 2004