Johnston Family - "Of Islington".

The Johnston Family holds a special place in the history of the Islington area of Etobicoke as they were its first permanent settlers - and stayed for 177 years! The Johnstons were originally a Lowland Scots family that moved to Northern Ireland where Benjamin Johnston was born around 1740. He travelled across the Atlantic Ocean sometime prior to the American Revolution and settled in Pennsylvania where he owned land which today would be within the City of Philadelphia. Benjamin married Elizabeth Young in Philadelphia in 1763, and they had a son George in 1764.

Part 1: Settling in Islington

As an adult, George acquired property on a tributary of the Ohio River, near today’s Pittsburgh. Around 1790, he married Mary (born 1773.) George and Mary had five children while living on their farm in Pennsylvania: Jane in 1791, Thomas in 1792, Henry in 1793, James in 1794 and William in 1795.

In 1798, George and Mary left Pennsylvania with their family and moved to Upper Canada. Their reasons for moving are not certain, but it is possible that they moved to escape recent problems in the Ohio Valley. With settlers streaming onto lands that many First Nations still felt was theirs, the resulting conflict had led to the Northwest Indian War. The US government built a new fort at Pittsburgh in 1791 to help protect this frontier. Although peace treaties were signed in 1795, there were no assurances that the situation would remain stable. This unsettled environment, coupled with the possibility of free land grants in Upper Canada offered by Lt. Gov. John Graves Simcoe, enticed many settlers from Pennsylvania and other north eastern states into Canada. This group of immigrants to Canada were referred to as “Late Loyalists.”

Before George and Mary left their American home, they buried many of their possessions near the river on their farm, expecting to come back later to repossess them, although they never did. They travelled north to the Niagara River in a Conestoga wagon, with several sheep and pigs, and 20 cows, trailing along behind. Many mornings they discovered that some of their possessions had been quietly taken by local indigenous people during the night. By the time they reached Niagara, only two cows remained. However, they had brought their most precious possessions with them in a hand-made walnut chest which survived the trip. (A descendant, Margaret Jane Nunn, donated this chest to “Dundurn Museum” prior to 1960. The Registrar of Hamilton’s museums is unable to locate this artefact today.)

The family crossed the Niagara River into Canada - with their two cows - on a raft they built by hand. Family lore says they first lived in the Hamilton area, and while possible, this could not be verified. George Johnston did not petition for land in Etobicoke until 1815, and in that petition, he stated that he had been renting in Upper Canada for 17 years. Official records exist of government leases of property from that time period, but no records were kept of people who rented land from individual property owners. This makes finding the Johnston family’s initial whereabouts after arrival almost impossible to trace. We do know that they were not listed as inhabitants of Etobicoke in an 1808 local census that was conducted, but they were there by late 1810 when two sons, Thomas and Henry, enlisted in a 3rd York Militia Flank Company.

George and Mary’s sixth child, Martha, was born in Upper Canada in 1798, followed by three sons, John in 1806, George ca. 1807 and Benjamin ca. 1808.

When the Johnstons moved to Etobicoke, they travelled along the north shore of Lake Ontario in flat-bottomed boats, with their belongings, to the Humber River. They ventured up the river to “the Head of Still Water” (i.e. the head of navigation, about where Bloor Street crosses the Humber River today.) They were surprised to find apple trees growing on the river flats, and they encountered a bear, which fell to Thomas’s firearm. The family then walked west along a rough trail, past Mimico Creek, and built their first home - a log cabin - on what today would be the north side of Dundas Street, near Royalavon Crescent, on Clergy Reserve Lot 7, Concession A. There is no record of anyone leasing this lot prior to the Johnstons’ arrival and they were likely “squatting” on the property until they received a lease in 1816. This lease remained in the family until 1840.

This area was initially called “Mimico” after the nearby creek. The word comes from the Mississauga First Nation word Omimeca, meaning “place where the wild pigeons nest.” In 1858, when the area needed a post office, the name Mimico had already been claimed by the village on Lake Ontario at the mouth of the creek. The village on Dundas was renamed “Islington”, after the birthplace of Elizabeth Smith, wife of local hotel owner Thomas Smith.

It took many years of hard labour for the Johnstons to create a farm out of the densely-forested land. Initially the family had to be completely self-sufficient as there were no services: no stores, no schools, no churches, no roads and no post office. As soon as they had cleared enough trees, George planted wheat and other grains among the stumps. After they harvested the grain, they would take it in sacks by horseback to one of the local grist mills: Silverthorn’s on Etobicoke Creek, or the King’s Mill on the Humber River.

There were beaver dams all up and down Mimico Creek, and these little animals had cut the trees down so closely that the land around the creek made good cattle pasture. Partridges, quail, and deer were abundant, and the Humber River was full of salmon.

It was said that Mary rarely smiled due to the hardships she had experienced in both Pennsylvania and Upper Canada. The women made the family’s clothes from home grown flax, longing for a time when they would not have to wear coarse linen in summer’s heat. After the War of 1812 they were finally able to buy inexpensive cotton fabric at the York Garrison – the closest thing they had to a store. Because there was a severe cash shortage in Canada, most “purchasing” in those days was conducted through barter. The only items that required a cash payment were salt and property taxes. Both salt and cash could be obtained at the York Garrison in exchange for home-grown products. To get to the garrison, the Johnstons walked two and a half miles to the Humber River where they had a dugout canoe tied up, and then paddled down the river to Lake Ontario and east to the Garrison.

Mary received frequent visits from Mississauga First Nation men coming down the Mimico Creek valley from the north where they had been hunting and trapping. Mary would always give them fresh milk to drink, which they considered a great treat. In exchange they would always leave Mary some fresh meat or an animal skin.

Three of George and Mary’s sons served in the York Militia during the War of 1812 - Thomas, Henry and William. They perfectly fit the profile of the typical young militia man in Upper Canada: born in Pennsylvania, in the early 1790s, Methodist, and from a Late Loyalist family. Dispelling a common myth, all of the Johnstons’ sons stood six feet or taller, which would have placed the three serving in the war at the front of any battle formations. Thankfully all three survived unscathed, although Thomas became very ill while serving on the Niagara Peninsula, and Mary traveled to his location to nurse him back to health. On April 13, 1813, during the Battle of York, son Benjamin - only five years old at the time - clearly remembered for his whole life the sound of the powder magazine being blown up in the York Garrison about nine miles away. The concussion from the explosion shook the Johnstons’ cabin, rattling its windows.

By 1810, Dundas Street from downtown York had been connected with Cooper’s Mills on the east side of the Humber River, where Old Dundas Street is today. However, the road did not connect with Dundas in Etobicoke, making it difficult to transport troops and supplies during the war. In June 1814, a new route for Dundas was surveyed through Etobicoke to connect Cooper’s Mills on the east with points west. This resulted in Dundas Street being moved further north, along the route it takes today. However, this new route now ran right outside the front door of the Johnston cabin, cutting off part of their lot. The family found the noise and dust from troops and supply convoys passing by unbearable. One day the horses of soldiers almost trampled one of the Johnstons’ young sons. As a result, on October 31, 1815 George Johnston bought Lot 16, Conc. 1 North Division Fronting the Lake from Andrew Morrow for 62 pounds. This 100-acre lot ran along the west side of Kipling Avenue, between Bloor Street and Burnhamthorpe Road. By 1816, George had built a new house for his family – a white stucco over frame Regency cottage they called “Pine Lodge,” just south of Burnhamthorpe and as far as possible from “the noise and dust of Dundas Street.”

In 1798, George and Mary left Pennsylvania with their family and moved to Upper Canada. Their reasons for moving are not certain, but it is possible that they moved to escape recent problems in the Ohio Valley. With settlers streaming onto lands that many First Nations still felt was theirs, the resulting conflict had led to the Northwest Indian War. The US government built a new fort at Pittsburgh in 1791 to help protect this frontier. Although peace treaties were signed in 1795, there were no assurances that the situation would remain stable. This unsettled environment, coupled with the possibility of free land grants in Upper Canada offered by Lt. Gov. John Graves Simcoe, enticed many settlers from Pennsylvania and other north eastern states into Canada. This group of immigrants to Canada were referred to as “Late Loyalists.”

Before George and Mary left their American home, they buried many of their possessions near the river on their farm, expecting to come back later to repossess them, although they never did. They travelled north to the Niagara River in a Conestoga wagon, with several sheep and pigs, and 20 cows, trailing along behind. Many mornings they discovered that some of their possessions had been quietly taken by local indigenous people during the night. By the time they reached Niagara, only two cows remained. However, they had brought their most precious possessions with them in a hand-made walnut chest which survived the trip. (A descendant, Margaret Jane Nunn, donated this chest to “Dundurn Museum” prior to 1960. The Registrar of Hamilton’s museums is unable to locate this artefact today.)

The family crossed the Niagara River into Canada - with their two cows - on a raft they built by hand. Family lore says they first lived in the Hamilton area, and while possible, this could not be verified. George Johnston did not petition for land in Etobicoke until 1815, and in that petition, he stated that he had been renting in Upper Canada for 17 years. Official records exist of government leases of property from that time period, but no records were kept of people who rented land from individual property owners. This makes finding the Johnston family’s initial whereabouts after arrival almost impossible to trace. We do know that they were not listed as inhabitants of Etobicoke in an 1808 local census that was conducted, but they were there by late 1810 when two sons, Thomas and Henry, enlisted in a 3rd York Militia Flank Company.

George and Mary’s sixth child, Martha, was born in Upper Canada in 1798, followed by three sons, John in 1806, George ca. 1807 and Benjamin ca. 1808.

When the Johnstons moved to Etobicoke, they travelled along the north shore of Lake Ontario in flat-bottomed boats, with their belongings, to the Humber River. They ventured up the river to “the Head of Still Water” (i.e. the head of navigation, about where Bloor Street crosses the Humber River today.) They were surprised to find apple trees growing on the river flats, and they encountered a bear, which fell to Thomas’s firearm. The family then walked west along a rough trail, past Mimico Creek, and built their first home - a log cabin - on what today would be the north side of Dundas Street, near Royalavon Crescent, on Clergy Reserve Lot 7, Concession A. There is no record of anyone leasing this lot prior to the Johnstons’ arrival and they were likely “squatting” on the property until they received a lease in 1816. This lease remained in the family until 1840.

This area was initially called “Mimico” after the nearby creek. The word comes from the Mississauga First Nation word Omimeca, meaning “place where the wild pigeons nest.” In 1858, when the area needed a post office, the name Mimico had already been claimed by the village on Lake Ontario at the mouth of the creek. The village on Dundas was renamed “Islington”, after the birthplace of Elizabeth Smith, wife of local hotel owner Thomas Smith.

It took many years of hard labour for the Johnstons to create a farm out of the densely-forested land. Initially the family had to be completely self-sufficient as there were no services: no stores, no schools, no churches, no roads and no post office. As soon as they had cleared enough trees, George planted wheat and other grains among the stumps. After they harvested the grain, they would take it in sacks by horseback to one of the local grist mills: Silverthorn’s on Etobicoke Creek, or the King’s Mill on the Humber River.

There were beaver dams all up and down Mimico Creek, and these little animals had cut the trees down so closely that the land around the creek made good cattle pasture. Partridges, quail, and deer were abundant, and the Humber River was full of salmon.

It was said that Mary rarely smiled due to the hardships she had experienced in both Pennsylvania and Upper Canada. The women made the family’s clothes from home grown flax, longing for a time when they would not have to wear coarse linen in summer’s heat. After the War of 1812 they were finally able to buy inexpensive cotton fabric at the York Garrison – the closest thing they had to a store. Because there was a severe cash shortage in Canada, most “purchasing” in those days was conducted through barter. The only items that required a cash payment were salt and property taxes. Both salt and cash could be obtained at the York Garrison in exchange for home-grown products. To get to the garrison, the Johnstons walked two and a half miles to the Humber River where they had a dugout canoe tied up, and then paddled down the river to Lake Ontario and east to the Garrison.

Mary received frequent visits from Mississauga First Nation men coming down the Mimico Creek valley from the north where they had been hunting and trapping. Mary would always give them fresh milk to drink, which they considered a great treat. In exchange they would always leave Mary some fresh meat or an animal skin.

Three of George and Mary’s sons served in the York Militia during the War of 1812 - Thomas, Henry and William. They perfectly fit the profile of the typical young militia man in Upper Canada: born in Pennsylvania, in the early 1790s, Methodist, and from a Late Loyalist family. Dispelling a common myth, all of the Johnstons’ sons stood six feet or taller, which would have placed the three serving in the war at the front of any battle formations. Thankfully all three survived unscathed, although Thomas became very ill while serving on the Niagara Peninsula, and Mary traveled to his location to nurse him back to health. On April 13, 1813, during the Battle of York, son Benjamin - only five years old at the time - clearly remembered for his whole life the sound of the powder magazine being blown up in the York Garrison about nine miles away. The concussion from the explosion shook the Johnstons’ cabin, rattling its windows.

By 1810, Dundas Street from downtown York had been connected with Cooper’s Mills on the east side of the Humber River, where Old Dundas Street is today. However, the road did not connect with Dundas in Etobicoke, making it difficult to transport troops and supplies during the war. In June 1814, a new route for Dundas was surveyed through Etobicoke to connect Cooper’s Mills on the east with points west. This resulted in Dundas Street being moved further north, along the route it takes today. However, this new route now ran right outside the front door of the Johnston cabin, cutting off part of their lot. The family found the noise and dust from troops and supply convoys passing by unbearable. One day the horses of soldiers almost trampled one of the Johnstons’ young sons. As a result, on October 31, 1815 George Johnston bought Lot 16, Conc. 1 North Division Fronting the Lake from Andrew Morrow for 62 pounds. This 100-acre lot ran along the west side of Kipling Avenue, between Bloor Street and Burnhamthorpe Road. By 1816, George had built a new house for his family – a white stucco over frame Regency cottage they called “Pine Lodge,” just south of Burnhamthorpe and as far as possible from “the noise and dust of Dundas Street.”

When George Johnston died in 1824 (age 60), he was buried on the family farm, as was his wife, Mary, when she died in 1846 (age 73.) Later, their grandson James helped move their remains to the Islington Burying Ground, on Dundas Street in Islington Village. George and Mary’s son, Benjamin, and his wife Hannah, were also buried in this cemetery. The original marble headstones still exist, mounted in a “memorial wall” built when the cemetery was restored in 1988. At the same time, a new granite headstone was erected by a descendant to mark the actual Johnston grave site.

The Johnstons planted apple seeds they had brought from Pennsylvania - mainly winter apples, pears and plums. Apples eventually became the mainstay of their highly successful family farm, which existed through the generations until the 1960s.

The Johnstons were the first permanent settlers in what became the Village of Islington. Eventually six generations of Johnstons would live on Lot 16, Conc.1, with the last piece of land sold off in 1985 by a 5th generation descendant. As of 2016, four former Johnston houses still stand in Islington: 1056, 1078 and 1100 Kipling Avenue and 66 Burnhamthorpe Road. All except 1056 Kipling are listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register.

Part 2: The Second Generation

George and Mary Johnston of Islington had nine children and a farm on the west side of Kipling Avenue, south of Burnhamthorpe Road. George died intestate in 1824 and, as the law dictated, the eldest son, Thomas, inherited the entire property. But what about the rest of the children… how did they fare without Thomas’ advantage? Who remained in the Islington area and who left? For those who left, where did they go, and what were their lives like? And did they stay in touch with each other?

JANE

The eldest child, Jane, was born in Pennsylvania in 1791. In 1811, she married William Bull Sheldon in York (Toronto). William was born in the USA in 1791. His family moved to Lower Canada when he was young, and he moved to Upper Canada ca. 1808. He and Jane had five children: Jane (1815-1904); Mary (1816-1890); Martha (1818-?); George C. (1820-?); and William Jr. (1825-1853.) William served in a 3rd York Militia Flank Company during the War of 1812. By 1814, he and Jane were living in Hamilton. William opened the town’s first store at King and John Streets, which he operated until 1829. By 1833 Jane and William owned a town lot in the Village of Ancaster and eight farm lots in Barton Township. William was a stockholder in the London and Gore Railway, and a shareholder in the Gore Bank.

William entered into the partnership of Sheldon, Dutcher & Co., a steam engine manufactory in Hamilton which moved to York by 1828. In 1833, William mortgaged most of his private property to finance a major expansion of this business. Plagued with quality and delivery problems, the business was the subject of 31 law suits between 1834 and 1838. In 1836 the company was forced into bankruptcy by the Bank of Upper Canada. At the time, they were the largest employer in Toronto with 80 employees.

William died in 1854 and Jane in 1855. Both are buried in Hamilton Cemetery.

THOMAS

Thomas was born in Pennsylvania in 1792. He was the only one of George and Mary’s children never to marry. In the War of 1812, Thomas served as a private in a 3rd York Militia Flank company. He fought in the Battles of Fort Detroit and Queenston Heights, and then worked on construction projects at the York Garrison for the balance of the war. For his service he received a 100-acre land grant in Caledon Township, and a General Service Medal for the Battle of Fort Detroit.

As eldest son, Thomas inherited 100-acre Lot 16, Conc. 1 when his father died in 1824. He also assumed his father’s lease on Clergy Block Lot 7, Conc. A. Thomas sold the north half of Lot 16, including the family home, to his youngest brother, Benjamin, in 1832, and sold him the south half in 1840.

Thomas continued to live on Lot 16 in an existing log cabin. He was a farmer and a trained surveyor, but also invested in real estate. He kept a good library for that time and was one of the initial three trustees of the first school built in Islington in 1834. Three additional generations of Johnstons went on be school trustees in Islington until 1953 – 119 years.

In the mid-1850s, Thomas moved in with his brother, John, and John’s wife Hannah, in North Dorchester Township, Middlesex County, near Ingersoll. He died there on June 29, 1859 at age 67.

HENRY

Henry was born in 1793 in Pennsylvania. Ca. 1833 he married Jane (1794-1864.) They had four children: Henry Jr. (1834-1886); George (1836-1855); Martha (1836-?); and Jane (1839-?).

Henry served as a private in a 3rd York Militia Flank Company. However, a British Army record from 1813 lists him as a “deserter,” so he was not entitled to a free land grant.

In 1833, Henry and Jane purchased the south 50 acres of Lot 37, Conc. 2 in the Smithfield area of northern Etobicoke. They sold 13 acres of the property in 1834, and the remainder in 1842, possibly because Henry was ill.

By the 1852 census, Henry had died and Jane was living alone in a rented log cabin in Lambton Mills. Perhaps she was having financial or health problems that made it impossible for her to look after her children, because in 1852 all four of them were living in North Dorchester Township, Middlesex County. Henry Jr. and George were living with John and Hannah Johnston, Henry Senior’s brother and sister-in-law. Martha was living in a log cabin on a farm near John and Hannah with a John Johnston, who was likely her cousin and one of William’s sons (see below.) Jane was a student living with a nearby family named Menhennick.

By 1855, Henry Senior’s son George was terminally ill and wrote a will, identifying his specific bequests to his three siblings, Uncle John and Aunt Hannah, but he left nothing to his mother, who passed away in 1864 and is buried in St. George’s Anglican Church-on-the-Hill cemetery.

JAMES

James was born in 1794 in Pennsylvania. He had a very successful farm in Trafalgar Township, Halton County, near his brother William. James married three times:

Over time, James changed the spelling of his surname to be Johnson. He died in 1855 and is buried in Milton, Halton County. Anne died in 1881 in Halton County.

WILLIAM

William was born in Pennsylvania in 1795. He married Anne Stewart (1805-1881) in 1823 in York. They had 6 children: Julia Ann (1824-?); Mary Jane (1826-?); John (1828-?); William (1831-?); Thomas (1836-?); and Benjamin (1838-1908.)

William served in the Embodied Militia during the War of 1812. He applied for a land grant and received one in Trafalgar Township, Halton County, near his brother James. He farmed there until his untimely death “in Etobicoke Township on or about the last of February” in 1838. Perhaps he was visiting his family in Etobicoke when he fell ill or had a fatal accident.

At the time of his death, William had built a house and barn, and improved 30 acres of his Trafalgar property, but letters patent had not yet been issued to him to signify ownership. In 1840, his wife, Anne, filed a claim with the Crown through the Heir & Devisee Commission on behalf of her four sons so they could remain on the land and inherit it when they became of age. Her request was granted, and by the 1861 census, the two youngest sons, Thomas and Benjamin, were farming on their father’s former property.

William’s widow Anne married his brother James in 1842 (see above under James.)

MARTHA

Martha was born in Upper Canada in 1798. In 1817, she married George B. Cary in York. They had six children: Jane (1819–1852); John Erasmus (1821–1874); George (1823–1889); James C (1825–1898); Harriet (1828–1832); Benjamin Thomas (1830-?).

George B. Cary was the son of United Empire Loyalist Bernard Cary who fought for the British in the American Revolution. After the war, Bernard returned to England where George was born in 1781. In 1795, Bernard received £30 for his war service and moved his family to Upper Canada.

In the War of 1812, George Cary served in a 3rd York Militia Flank Company where he “deserted and [was] useless upon all occasions.”

George and Martha moved to Hamilton early in their marriage, but the date, location and his occupation are unknown. Martha died in Hamilton in 1839. George remarried in 1841 to Anna Merriman, and moved to Ohio where he lived with his son, George, and worked as a carpenter until his death in 1852.

JOHN

John was born in 1806 in Upper Canada. In 1833 he married Hannah (1817-?) in Upper Canada. They had one child, Sary (Sarah) Ann, born in 1844.

They bought a farm in North Dorchester Township, Middlesex County, near Ingersoll, and lived in a one-storey “log shanty.” In 1852, John’s nephews Henry Jr. and George Johnston, sons of Henry and Jane, were living with them. Niece Martha was living nearby with a John Johnston - likely her cousin, one of William’s sons. Niece Jane was living with a neighbour named Menhennick. John’s nephew George died in 1855, but his nephew Henry was still living with them in 1861. In the mid-1850s, John’s eldest brother Thomas moved in with them and died there in 1859.

John died between 1861and 1864, and Hannah between 1861 and 1869.

GEORGE JR.

All Johnston Family memoirs report that George and Mary Johnston had two daughters and seven sons. There is a family story that a young George Johnston was almost trampled by the horses of soldiers passing by the family’s log cabin on Dundas Street in 1814. However, there is no definitive proof that there was a son named George.

The strongest support for his existence may be found in the land registry records for the Johnstons’ Kipling Avenue property. In 1848, long after the death of the George who originally settled in Islington, Samuel Wood, their neighbour to the south, obtained a mortgage for £350 from a “George Johnston”, which he paid off in 1855. There definitely were quite a few George Johnstons in the province, but nothing specifically connects any of them with the Johnstons in Islington.

If we assume that if George Jr. did exist, a likely birth year for him would be about 1807.

BENJAMIN

Benjamin was born ca. 1808 in Upper Canada, the youngest child of George and Mary Johnston. In 1833, Benjamin married Hannah Mattice of Etobicoke, and they had five children: James (1836-1925); Martha (1838-1930); William (1841-1916); Mary Ann (1846-1900); and Benjamin Jr. (1848-1924.)

In 1832, Thomas sold the north half of Lot 16, including the original family home and barns, to Benjamin. This 50-acre property was owned by his descendants until 1985, and three of the four Johnston houses that still exist today are on this property.

Benjamin became a prominent land owner in the Islington area. He was a “gentleman farmer” and hired a manager to run his successful farm. He was also somewhat of a dandy, always dressed in a frock coat, stand-up collar, flowing tie and top hat. His wife Hannah, was more plain and forthright. She descended from Dutch Loyalist stock in New York State who had settled in Etobicoke in 1811.

In 1864, when Benjamin was executor for Thomas’ estate, he wrote that he was “the only surviving brother.” He died in 1878 and Hannah passed away in 1893. They are buried in the Islington Burying Ground.

While some of George and Mary’s children were more financially successful than others, it also appears that the siblings stayed in touch and supported each other through the years.

As further proof of the family’s closeness, one need only have a look at what they named their children: the names of all nine siblings and their parents, are represented multiple times – something that continued through subsequent generations.

JANE

The eldest child, Jane, was born in Pennsylvania in 1791. In 1811, she married William Bull Sheldon in York (Toronto). William was born in the USA in 1791. His family moved to Lower Canada when he was young, and he moved to Upper Canada ca. 1808. He and Jane had five children: Jane (1815-1904); Mary (1816-1890); Martha (1818-?); George C. (1820-?); and William Jr. (1825-1853.) William served in a 3rd York Militia Flank Company during the War of 1812. By 1814, he and Jane were living in Hamilton. William opened the town’s first store at King and John Streets, which he operated until 1829. By 1833 Jane and William owned a town lot in the Village of Ancaster and eight farm lots in Barton Township. William was a stockholder in the London and Gore Railway, and a shareholder in the Gore Bank.

William entered into the partnership of Sheldon, Dutcher & Co., a steam engine manufactory in Hamilton which moved to York by 1828. In 1833, William mortgaged most of his private property to finance a major expansion of this business. Plagued with quality and delivery problems, the business was the subject of 31 law suits between 1834 and 1838. In 1836 the company was forced into bankruptcy by the Bank of Upper Canada. At the time, they were the largest employer in Toronto with 80 employees.

William died in 1854 and Jane in 1855. Both are buried in Hamilton Cemetery.

THOMAS

Thomas was born in Pennsylvania in 1792. He was the only one of George and Mary’s children never to marry. In the War of 1812, Thomas served as a private in a 3rd York Militia Flank company. He fought in the Battles of Fort Detroit and Queenston Heights, and then worked on construction projects at the York Garrison for the balance of the war. For his service he received a 100-acre land grant in Caledon Township, and a General Service Medal for the Battle of Fort Detroit.

As eldest son, Thomas inherited 100-acre Lot 16, Conc. 1 when his father died in 1824. He also assumed his father’s lease on Clergy Block Lot 7, Conc. A. Thomas sold the north half of Lot 16, including the family home, to his youngest brother, Benjamin, in 1832, and sold him the south half in 1840.

Thomas continued to live on Lot 16 in an existing log cabin. He was a farmer and a trained surveyor, but also invested in real estate. He kept a good library for that time and was one of the initial three trustees of the first school built in Islington in 1834. Three additional generations of Johnstons went on be school trustees in Islington until 1953 – 119 years.

In the mid-1850s, Thomas moved in with his brother, John, and John’s wife Hannah, in North Dorchester Township, Middlesex County, near Ingersoll. He died there on June 29, 1859 at age 67.

HENRY

Henry was born in 1793 in Pennsylvania. Ca. 1833 he married Jane (1794-1864.) They had four children: Henry Jr. (1834-1886); George (1836-1855); Martha (1836-?); and Jane (1839-?).

Henry served as a private in a 3rd York Militia Flank Company. However, a British Army record from 1813 lists him as a “deserter,” so he was not entitled to a free land grant.

In 1833, Henry and Jane purchased the south 50 acres of Lot 37, Conc. 2 in the Smithfield area of northern Etobicoke. They sold 13 acres of the property in 1834, and the remainder in 1842, possibly because Henry was ill.

By the 1852 census, Henry had died and Jane was living alone in a rented log cabin in Lambton Mills. Perhaps she was having financial or health problems that made it impossible for her to look after her children, because in 1852 all four of them were living in North Dorchester Township, Middlesex County. Henry Jr. and George were living with John and Hannah Johnston, Henry Senior’s brother and sister-in-law. Martha was living in a log cabin on a farm near John and Hannah with a John Johnston, who was likely her cousin and one of William’s sons (see below.) Jane was a student living with a nearby family named Menhennick.

By 1855, Henry Senior’s son George was terminally ill and wrote a will, identifying his specific bequests to his three siblings, Uncle John and Aunt Hannah, but he left nothing to his mother, who passed away in 1864 and is buried in St. George’s Anglican Church-on-the-Hill cemetery.

JAMES

James was born in 1794 in Pennsylvania. He had a very successful farm in Trafalgar Township, Halton County, near his brother William. James married three times:

- Ca. 1811 to an unknown wife. They had one son, Cornelius (1812-1871.)

- In 1823 to Mary Elizabeth Kitely (1794-1842.) They had six children: Mary (1824-?); Sarah (1826-?); Elizabeth Jane (1829-52); James Henry (1831-74); John Copeland (1833-1902); and Lydia Margaret (1836-1903)

- In 1842 to Anne (1805-1881) who was the widow of James’ brother, William (see below). They had one child, Julia Ann (1843-83.)

Over time, James changed the spelling of his surname to be Johnson. He died in 1855 and is buried in Milton, Halton County. Anne died in 1881 in Halton County.

WILLIAM

William was born in Pennsylvania in 1795. He married Anne Stewart (1805-1881) in 1823 in York. They had 6 children: Julia Ann (1824-?); Mary Jane (1826-?); John (1828-?); William (1831-?); Thomas (1836-?); and Benjamin (1838-1908.)

William served in the Embodied Militia during the War of 1812. He applied for a land grant and received one in Trafalgar Township, Halton County, near his brother James. He farmed there until his untimely death “in Etobicoke Township on or about the last of February” in 1838. Perhaps he was visiting his family in Etobicoke when he fell ill or had a fatal accident.

At the time of his death, William had built a house and barn, and improved 30 acres of his Trafalgar property, but letters patent had not yet been issued to him to signify ownership. In 1840, his wife, Anne, filed a claim with the Crown through the Heir & Devisee Commission on behalf of her four sons so they could remain on the land and inherit it when they became of age. Her request was granted, and by the 1861 census, the two youngest sons, Thomas and Benjamin, were farming on their father’s former property.

William’s widow Anne married his brother James in 1842 (see above under James.)

MARTHA

Martha was born in Upper Canada in 1798. In 1817, she married George B. Cary in York. They had six children: Jane (1819–1852); John Erasmus (1821–1874); George (1823–1889); James C (1825–1898); Harriet (1828–1832); Benjamin Thomas (1830-?).

George B. Cary was the son of United Empire Loyalist Bernard Cary who fought for the British in the American Revolution. After the war, Bernard returned to England where George was born in 1781. In 1795, Bernard received £30 for his war service and moved his family to Upper Canada.

In the War of 1812, George Cary served in a 3rd York Militia Flank Company where he “deserted and [was] useless upon all occasions.”

George and Martha moved to Hamilton early in their marriage, but the date, location and his occupation are unknown. Martha died in Hamilton in 1839. George remarried in 1841 to Anna Merriman, and moved to Ohio where he lived with his son, George, and worked as a carpenter until his death in 1852.

JOHN

John was born in 1806 in Upper Canada. In 1833 he married Hannah (1817-?) in Upper Canada. They had one child, Sary (Sarah) Ann, born in 1844.

They bought a farm in North Dorchester Township, Middlesex County, near Ingersoll, and lived in a one-storey “log shanty.” In 1852, John’s nephews Henry Jr. and George Johnston, sons of Henry and Jane, were living with them. Niece Martha was living nearby with a John Johnston - likely her cousin, one of William’s sons. Niece Jane was living with a neighbour named Menhennick. John’s nephew George died in 1855, but his nephew Henry was still living with them in 1861. In the mid-1850s, John’s eldest brother Thomas moved in with them and died there in 1859.

John died between 1861and 1864, and Hannah between 1861 and 1869.

GEORGE JR.

All Johnston Family memoirs report that George and Mary Johnston had two daughters and seven sons. There is a family story that a young George Johnston was almost trampled by the horses of soldiers passing by the family’s log cabin on Dundas Street in 1814. However, there is no definitive proof that there was a son named George.

The strongest support for his existence may be found in the land registry records for the Johnstons’ Kipling Avenue property. In 1848, long after the death of the George who originally settled in Islington, Samuel Wood, their neighbour to the south, obtained a mortgage for £350 from a “George Johnston”, which he paid off in 1855. There definitely were quite a few George Johnstons in the province, but nothing specifically connects any of them with the Johnstons in Islington.

If we assume that if George Jr. did exist, a likely birth year for him would be about 1807.

BENJAMIN

Benjamin was born ca. 1808 in Upper Canada, the youngest child of George and Mary Johnston. In 1833, Benjamin married Hannah Mattice of Etobicoke, and they had five children: James (1836-1925); Martha (1838-1930); William (1841-1916); Mary Ann (1846-1900); and Benjamin Jr. (1848-1924.)

In 1832, Thomas sold the north half of Lot 16, including the original family home and barns, to Benjamin. This 50-acre property was owned by his descendants until 1985, and three of the four Johnston houses that still exist today are on this property.

Benjamin became a prominent land owner in the Islington area. He was a “gentleman farmer” and hired a manager to run his successful farm. He was also somewhat of a dandy, always dressed in a frock coat, stand-up collar, flowing tie and top hat. His wife Hannah, was more plain and forthright. She descended from Dutch Loyalist stock in New York State who had settled in Etobicoke in 1811.

In 1864, when Benjamin was executor for Thomas’ estate, he wrote that he was “the only surviving brother.” He died in 1878 and Hannah passed away in 1893. They are buried in the Islington Burying Ground.

While some of George and Mary’s children were more financially successful than others, it also appears that the siblings stayed in touch and supported each other through the years.

- Jane and Martha – the only two daughters – both lived in the Hamilton area where they could continue their close relationship.

- James and William both lived in Trafalgar Township, Halton County, on farms only one concession apart. Likely William went there first because it was the location of his land grant, and James followed. William passed away on a trip home to Etobicoke. William’s widow Anne married James Johnston after his second wife died.

- John moved the furthest away from Etobicoke to Middlesex County. His “log shanty” home appears to have become a refuge for other family members. After John’s brother Henry died, Henry’s four children ended up living with or near John. It also appears that William’s son, John, became a farmer very near his Uncle John. John’s brother Thomas, in the mid-1850s, left Etobicoke and moved in with John and Hannah where he passed away there in 1859.

- Henry stayed in Etobicoke, buying a lot and living there until something broke up the family – likely Henry’s illness and subsequent death. But his children were safely looked after by his brother John.

- Thomas and Benjamin stayed in Islington, and they appear to have been very close and financially successful. When Benjamin married, Thomas sold him the north half of the Kipling property with the house and barns. They lived on the same property and shared the farming work.

As further proof of the family’s closeness, one need only have a look at what they named their children: the names of all nine siblings and their parents, are represented multiple times – something that continued through subsequent generations.

Part 3: Benjamin's Descendants

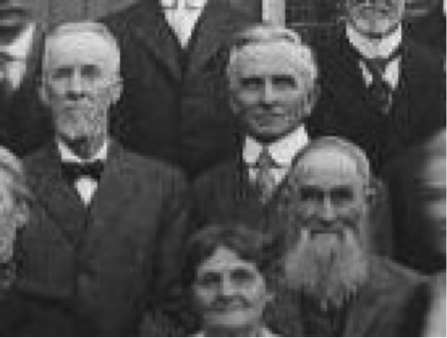

Benjamin Johnston’s eldest son and heir, James, was educated at the British American Business College on Yonge Street, but his real life’s passions were music and fruit growing.

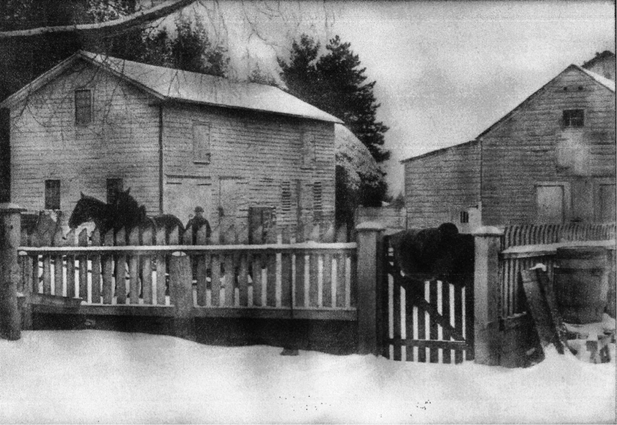

He was musically trained and loved to sing. At age 18 he was appointed music director at Islington Methodist Church. He met his wife, Matilda Ralston, in a singing group. After they married in 1866, they moved first to a farm in St. Mary’s, and then in 1870 to one in Erindale. By 1876, his father was not well and, as the eldest son, it was James’ duty to come home and take over the family farm. Matilda was not fond of the Pine Lodge house and felt that if they had to give up their farm in Erindale, they should build a new house in Islington. The 1816 house was demolished in 1876 and by 1878 a new one had been constructed on its footprint.

The new house, called “Pine Lodge” like its predecessor, is a tall, two-story dwelling built of red brick in a Gothic revival style. Its address today is 1078 Kipling Avenue, on the northwest corner of Kipling Avenue and Goswell Road, and it is listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register.

He was musically trained and loved to sing. At age 18 he was appointed music director at Islington Methodist Church. He met his wife, Matilda Ralston, in a singing group. After they married in 1866, they moved first to a farm in St. Mary’s, and then in 1870 to one in Erindale. By 1876, his father was not well and, as the eldest son, it was James’ duty to come home and take over the family farm. Matilda was not fond of the Pine Lodge house and felt that if they had to give up their farm in Erindale, they should build a new house in Islington. The 1816 house was demolished in 1876 and by 1878 a new one had been constructed on its footprint.

The new house, called “Pine Lodge” like its predecessor, is a tall, two-story dwelling built of red brick in a Gothic revival style. Its address today is 1078 Kipling Avenue, on the northwest corner of Kipling Avenue and Goswell Road, and it is listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register.

In June 1878, Benjamin passed away and James inherited the property. Now that he was back in Islington permanently, James resumed his position as music director at Islington Methodist Church, a position he eventually held for a total of 50 years. To honour this service, his family donated choir pews when Islington United Church was built in 1949.

Professionally, James was an expert in grafting fruit trees, and the area around their house was full of his tree “experiments”, such as a thorn tree with pears and apples grafted onto it that he grew “just for fun.” He once grafted 40 different apple varieties onto one tree, for which he earned a prize. He taught grafting at Guelph Agricultural College for many years. Driving down Kipling, you would see row after row of fruit trees, mostly Northern Spy apples and other winter varieties, many grown for export.

James and Matilda had seven children – two boys and five girls. The entire family loved music and either played an instrument or sang. Often the entire family would give concerts or perform at local parties and community events.

Professionally, James was an expert in grafting fruit trees, and the area around their house was full of his tree “experiments”, such as a thorn tree with pears and apples grafted onto it that he grew “just for fun.” He once grafted 40 different apple varieties onto one tree, for which he earned a prize. He taught grafting at Guelph Agricultural College for many years. Driving down Kipling, you would see row after row of fruit trees, mostly Northern Spy apples and other winter varieties, many grown for export.

James and Matilda had seven children – two boys and five girls. The entire family loved music and either played an instrument or sang. Often the entire family would give concerts or perform at local parties and community events.

Matilda was kind and generous to everyone. She was known to be an excellent cook, and whether her visitors were local children, neighbours or tramps, no one ever left her house hungry.

In 1894, James decided it was time to retire. Frederick, his eldest son, had been blind since the age of 14. Consequently, James handed the family business over to his second son, Arthur, aged 21. The Pine Lodge house was also given to Arthur, while James and Matilda built a new house for themselves that they called “Pine Cottage” on the southwest corner of Kipling Avenue and Burnhamthorpe Road. It was made of red brick with a slate roof and an open front verandah, but has since been painted white. Inside there was an elegant staircase, 11-foot ceilings and a marble fireplace. The house was surrounded with vegetable and flower gardens where Matilda’s prize-winning gladioli could be viewed. They lived in the house until their deaths: Matilda in 1923 and James in 1925. The address today is 1100 Kipling Avenue, and this property is also listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register.

In 1894, James decided it was time to retire. Frederick, his eldest son, had been blind since the age of 14. Consequently, James handed the family business over to his second son, Arthur, aged 21. The Pine Lodge house was also given to Arthur, while James and Matilda built a new house for themselves that they called “Pine Cottage” on the southwest corner of Kipling Avenue and Burnhamthorpe Road. It was made of red brick with a slate roof and an open front verandah, but has since been painted white. Inside there was an elegant staircase, 11-foot ceilings and a marble fireplace. The house was surrounded with vegetable and flower gardens where Matilda’s prize-winning gladioli could be viewed. They lived in the house until their deaths: Matilda in 1923 and James in 1925. The address today is 1100 Kipling Avenue, and this property is also listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register.

Arthur assumed responsibility for the family farm willingly and worked to modernize the farm’s operations. He also took over as choir director at Islington Methodist Church after his father stepped down. In 1903 he married Amy Mason of Etobicoke. They had three children: Eileen in 1903, Muriel in 1908, and George in 1913.

In 1903 Arthur built a third house on Kipling Avenue as a permanent residence for a “hired man” and his family. Today this house sits on a 100 foot by 150- foot lot at 1056 Kipling Avenue. It is the only one of four existing Johnston houses that is not listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register.

In 1903 Arthur built a third house on Kipling Avenue as a permanent residence for a “hired man” and his family. Today this house sits on a 100 foot by 150- foot lot at 1056 Kipling Avenue. It is the only one of four existing Johnston houses that is not listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register.

Arthur was one of three trustees appointed to administer James’ estate, which had been set up to support not only Arthur’s family but also an extended family that included his brother and several aunts. With family approval, Arthur invested in hundreds of acres of apple orchards across Ontario. When the Depression hit in 1929, apple prices fell, and their new orchard properties were worth nothing on the market. The trustees also discovered that the lawyer they had hired stole $100,000 from James’ estate, invested it and lost every penny. The lawyer went to jail, but the three trustees had to pay the $100,000 back into the estate. After Arthur died in 1939, family members would often say that “the Depression killed him” as a result of the worry and burden of responsibility he carried for his extended family.

In the 1930s, Arthur started to subdivide his Islington farm property. He named the road opened along its south border Mattice Avenue after the family of his grandmother, Hannah Mattice.

Arthur’s son George began helping on the farm at an early age. He attended Etobicoke High School when it opened in 1928. Few graduates could afford university during the Depression. To compensate, George and other young men in Islington aged 18 to 25, under the leadership of Islington resident Earle Gordon, founded The Order of the Knights of the Round Table to provide a type of continuing education. They studied economics, politics, science, art and many other fields. They put on an annual “Variety Show” and raised money for community service work. The Order spread to other locations in Ontario and endured for 30 years.

Arthur’s son George began helping on the farm at an early age. He attended Etobicoke High School when it opened in 1928. Few graduates could afford university during the Depression. To compensate, George and other young men in Islington aged 18 to 25, under the leadership of Islington resident Earle Gordon, founded The Order of the Knights of the Round Table to provide a type of continuing education. They studied economics, politics, science, art and many other fields. They put on an annual “Variety Show” and raised money for community service work. The Order spread to other locations in Ontario and endured for 30 years.

George was also interested in music, and played percussion in the Community Symphony of Islington. In 1939, he succeeded Arthur as school trustee, only stepping down in 1953 because of work commitments. Thus ended 119 years with a Johnston as a trustee of Islington’s public school.

After Arthur died in 1939, Pine Lodge was sold and his widow, Amy, moved into the now-vacant hired man’s house. By 1940 George had stopped farming and was working full time at Goodyear Tire in New Toronto. He soon moved to the Small Arms Division of Canadian Arsenals in Lakeview, and then to Moffats in Weston as Production Control Manager. After a plant strike, he started his own business, Commercial Draperies Ltd.

George met Gloria Pretty in 1960 in the Six Points Loblaws store when they literally crashed into each other with their shopping carts. Both were widowed, and they soon married and lived at 1056 Kipling. Their two children – Tracy born in 1962 and Scott in 1964 – became the 6th generation of Johnstons to live on the Kipling Avenue property. After Tracy and Scott finished university and moved out, their parents continued to live there until George’s 1985 retirement. They sold the house, making them the last Johnstons to live on the Kipling property. They moved into a log house they built on Peninsula Lake in Muskoka. Twelve years later, they moved to a retirement residence in Orillia where George died in 2007 and Gloria in 2011.

But there is still a fourth Johnston house remaining in Islington to talk about… the home of James’ youngest brother, Benjamin Jr. He had been born in 1848 in Pine Lodge. He married Mary Falconer in 1872 and they had three children: Henry in 1876, Hannah in 1879, and Sydney in 1891. In 1878 Benjamin bought, from his brother William, a 50-acre triangular parcel of land bound by Kipling Avenue, Burnhamthorpe Road, and Burnhamthorpe Crescent, and leased it to a tenant farmer. From 1878 to 1880, Benjamin and his family lived on St. Clarens Avenue in Brockton Village. They then moved to West Toronto Junction and farmed there until 1899 when they returned to live on their Islington property.

By 1907, Benjamin and Mary had built the grand house that is now 66 Burnhamthorpe Road, at the corner of Mattice Road and overlooking the Mimico Creek Valley. A plaque high in the peak of one of the its gables still displays the home’s name, “Valleyview”.

After Arthur died in 1939, Pine Lodge was sold and his widow, Amy, moved into the now-vacant hired man’s house. By 1940 George had stopped farming and was working full time at Goodyear Tire in New Toronto. He soon moved to the Small Arms Division of Canadian Arsenals in Lakeview, and then to Moffats in Weston as Production Control Manager. After a plant strike, he started his own business, Commercial Draperies Ltd.

George met Gloria Pretty in 1960 in the Six Points Loblaws store when they literally crashed into each other with their shopping carts. Both were widowed, and they soon married and lived at 1056 Kipling. Their two children – Tracy born in 1962 and Scott in 1964 – became the 6th generation of Johnstons to live on the Kipling Avenue property. After Tracy and Scott finished university and moved out, their parents continued to live there until George’s 1985 retirement. They sold the house, making them the last Johnstons to live on the Kipling property. They moved into a log house they built on Peninsula Lake in Muskoka. Twelve years later, they moved to a retirement residence in Orillia where George died in 2007 and Gloria in 2011.

But there is still a fourth Johnston house remaining in Islington to talk about… the home of James’ youngest brother, Benjamin Jr. He had been born in 1848 in Pine Lodge. He married Mary Falconer in 1872 and they had three children: Henry in 1876, Hannah in 1879, and Sydney in 1891. In 1878 Benjamin bought, from his brother William, a 50-acre triangular parcel of land bound by Kipling Avenue, Burnhamthorpe Road, and Burnhamthorpe Crescent, and leased it to a tenant farmer. From 1878 to 1880, Benjamin and his family lived on St. Clarens Avenue in Brockton Village. They then moved to West Toronto Junction and farmed there until 1899 when they returned to live on their Islington property.

By 1907, Benjamin and Mary had built the grand house that is now 66 Burnhamthorpe Road, at the corner of Mattice Road and overlooking the Mimico Creek Valley. A plaque high in the peak of one of the its gables still displays the home’s name, “Valleyview”.

The house was designed by the popular and prolific West Toronto Junction architect, James A. Ellis. This three-storey, imposing and eclectic house is built of red brick with large bay windows, tall chimneys, a front verandah, and intricate brick detailing. It is listed on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register.

In 1910, Benjamin sold 45 acres of his land which was later developed into a residential subdivision. From his new house, it was a short distance through a pine woods to the James Johnston house on Kipling. Benjamin was a great favourite with James’ children and visited often. Described as a gentle, sweet-tempered, kind man, he was also an avid reader and founded the first library in Islington. He served as its librarian until he was a senior citizen and almost blind. His wife Mary was described as his polar opposite, ruling the family with an iron rod as she endeavoured to keep everyone up to her high standards.

Benjamin died in 1924 and Mary in 1926. In 1934, their house was sold to Alexander Burr Loblaw, son of Theodore Pringle Loblaw, founder of the Loblaws grocery chain. The Loblaw family lived in the house until 1966.

Continue the story of this house when it was owned by the Loblaw family.

This ends the story of the Johnston family’s 177 years in Islington. But there are still scores of George and Mary Johnston’s descendants in other parts of Ontario. In doing this research, I was fortunate to meet in person or talk by phone with descendants from Colborne, Georgetown, Kingston and Drayton who generously shared information, photographs and stories with me. The information gathered now fills a three-inch thick binder in the library at Montgomery’s Inn where it shares shelf space with the family histories of the many other pioneers who laid the foundation for today’s Etobicoke.

All photos of Johnston family members courtesy of Tracy Johnston Robins. Photo of 1816 “Pine Lodge” courtesy of Lucinda Bray. Modern photos of houses taken by author.

Researched and Written by Denise Harris.

Continue the story of this house when it was owned by the Loblaw family.

This ends the story of the Johnston family’s 177 years in Islington. But there are still scores of George and Mary Johnston’s descendants in other parts of Ontario. In doing this research, I was fortunate to meet in person or talk by phone with descendants from Colborne, Georgetown, Kingston and Drayton who generously shared information, photographs and stories with me. The information gathered now fills a three-inch thick binder in the library at Montgomery’s Inn where it shares shelf space with the family histories of the many other pioneers who laid the foundation for today’s Etobicoke.

All photos of Johnston family members courtesy of Tracy Johnston Robins. Photo of 1816 “Pine Lodge” courtesy of Lucinda Bray. Modern photos of houses taken by author.

Researched and Written by Denise Harris.