Montgomery's Inn

Built in 1832, Montgomery's Inn stands today at 4709 Dundas Street West, on the southeast corner of Islington Avenue and Dundas Street West in Etobicoke. Now surrounded by a rapidly expanding metropolis, it continues to provide visual evidence of early 19th century life in this region.

The continued existence of this important heritage property however, was less secure in the early 1960s. At that time, it appeared that the building might be moved from its original location to Black Creek Pioneer Village, to allow the site to be developed. The local Etobicoke Historical Society, concerned that Etobicoke's rural past was quickly being eroded, and also concerned that the Inn would lose much of its significance if moved, began a long struggle to have the building preserved as an historic site on its original location.

The continued existence of this important heritage property however, was less secure in the early 1960s. At that time, it appeared that the building might be moved from its original location to Black Creek Pioneer Village, to allow the site to be developed. The local Etobicoke Historical Society, concerned that Etobicoke's rural past was quickly being eroded, and also concerned that the Inn would lose much of its significance if moved, began a long struggle to have the building preserved as an historic site on its original location.

The developer, Mr. Louis Mayzel, was fortuitously persuaded by Mr. Joe Anderson, president of the Etobicoke Historical Society, to sell the building to the society at his cost. Members of the Society guaranteed the required mortgage payments. The Society worked tirelessly to have the building preserved, and eventually transferred ownership to Etobicoke Township and lobbied for restoration of the building. The main section of the building is one of the province's finest remaining examples of Loyalist or late Georgian architecture. The main front door, surrounded by its sidelight and overhead fanlight, is typical of this style. Originally, the rubble stone exterior of the Inn with details pointed to resemble proper cut stone. This added to the formal Georgian appearance. To 20th-century eyes, however, the exposed stone appeared more visually attractive, and during the exterior restoration in 1967, the stucco was unfortunately removed.

In 1972, Napier Simpson Jr. and Dorothy Duncan, in consultation with Brigadier J. A. McGinnis, began the work of restoring the interior of Montgomery's Inn. Restoration was completed in 1975. Operated as an historic house museum by the Etobicoke Historical Board, the Inn opened again to the public in 1975, after having been closed after operating as an inn since about 1855. Today it is administered by the museum section of the Culture Department of the City of Toronto.

The History of the Inn

Thomas Montgomery (1790-1877), was a young man when he emigrated from County Fermanagh, Ireland, early in the 19th century. He brought with him, however, a good sense for business, and built the large stone inn on the busy east-west Dundas Highway. The surveyor, David Gibson, noted in his journal for June 15, 1831, "Come to T. Montgomery tavern on Dundas Street." This is one of the earliest references we have of the inn.

Business prospered, and Thomas expanded, adding new bar room and kitchen wings in 1838. Other buildings, including barns, a drive shed, outhouses and a smokehouse for preserving meat, were also constructed to complete the complex. Montgomery eventually acquired a site comprising approximately 400 acres. It extended from Dundas Street on the north to Bloor Street on the south, and from Kipling Avenue (Concession 1 fronting the Humber) on the west to Royal York Road (Concession B fronting the Humber) on the east. During his lifetime, he acquired over 200 pieces of property in Ontario, most of them between 1845 and 1870. At the time of his death in 1877, he left an estate valued at $154,000.

The interior of the Inn is now restored to the period of 1847-1850, when it served both as a busy hostelry and as a centre for community activities. The furniture and accessories reflect the taste of a conservative country innkeeper of that time period. They are Canadian, American and English in origin. Many of the pieces are of an earlier period, as the Inn would have been furnished with both old and new furniture when built.

The paint colours on the walls and woodwork are similar to the original colours, which were discovered by scraping down to the original coat of paint in each room. From the Montgomery Papers', we learn that, in June 1838, Thomas and John McClane, Senior and Junior, drew up a contract with Thomas Montgomery for building the addition. We also learn that, in 1846, Thomas Montgomery paid George E. Stout for "preparing and papering sitting room." The present paper is a reproduction of a mid-Victorian, moderately priced, "rococo revival" pattern. It was inspired by a sample of wallpaper salvaged from Briarly, an adjacent home, contemporary with the Inn, when it was demolished in 1990.

In 1972, Napier Simpson Jr. and Dorothy Duncan, in consultation with Brigadier J. A. McGinnis, began the work of restoring the interior of Montgomery's Inn. Restoration was completed in 1975. Operated as an historic house museum by the Etobicoke Historical Board, the Inn opened again to the public in 1975, after having been closed after operating as an inn since about 1855. Today it is administered by the museum section of the Culture Department of the City of Toronto.

The History of the Inn

Thomas Montgomery (1790-1877), was a young man when he emigrated from County Fermanagh, Ireland, early in the 19th century. He brought with him, however, a good sense for business, and built the large stone inn on the busy east-west Dundas Highway. The surveyor, David Gibson, noted in his journal for June 15, 1831, "Come to T. Montgomery tavern on Dundas Street." This is one of the earliest references we have of the inn.

Business prospered, and Thomas expanded, adding new bar room and kitchen wings in 1838. Other buildings, including barns, a drive shed, outhouses and a smokehouse for preserving meat, were also constructed to complete the complex. Montgomery eventually acquired a site comprising approximately 400 acres. It extended from Dundas Street on the north to Bloor Street on the south, and from Kipling Avenue (Concession 1 fronting the Humber) on the west to Royal York Road (Concession B fronting the Humber) on the east. During his lifetime, he acquired over 200 pieces of property in Ontario, most of them between 1845 and 1870. At the time of his death in 1877, he left an estate valued at $154,000.

The interior of the Inn is now restored to the period of 1847-1850, when it served both as a busy hostelry and as a centre for community activities. The furniture and accessories reflect the taste of a conservative country innkeeper of that time period. They are Canadian, American and English in origin. Many of the pieces are of an earlier period, as the Inn would have been furnished with both old and new furniture when built.

The paint colours on the walls and woodwork are similar to the original colours, which were discovered by scraping down to the original coat of paint in each room. From the Montgomery Papers', we learn that, in June 1838, Thomas and John McClane, Senior and Junior, drew up a contract with Thomas Montgomery for building the addition. We also learn that, in 1846, Thomas Montgomery paid George E. Stout for "preparing and papering sitting room." The present paper is a reproduction of a mid-Victorian, moderately priced, "rococo revival" pattern. It was inspired by a sample of wallpaper salvaged from Briarly, an adjacent home, contemporary with the Inn, when it was demolished in 1990.

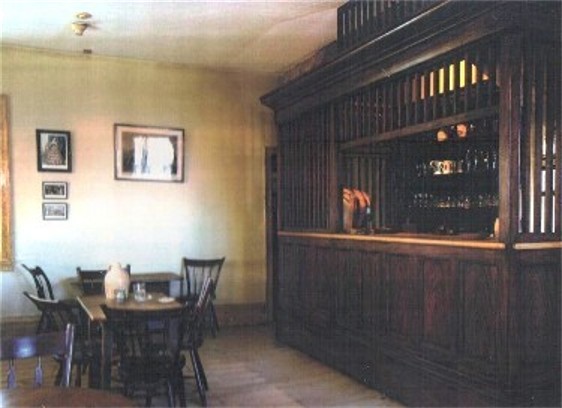

The bar room was a place for travellers and local farmers to drink, eat, and visit with each other. Thomas' account books show that whiskey was the most popular drink, but that he also sold peppermint and shrub (mixed drinks), beer, rum, brandy white wine, port, gin and sider".

On the second floor, the public bedrooms show the common practice of renting a space in a bed, rather than a room or even an entire bed to an individual. It was not uncommon for two or three people to share a bed. The busiest time for innkeepers, including Thomas Montgomery, would be the winter months, when the farm population had the most leisure time, and the snow-covered, frozen roads were most favourable for travel. These travellers would probably welcome the opportunity to sleep in a bed with someone else in an attempt to keep warm!

The Thomas Montgomery Papers, deposited in the Baldwin Room of the Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library and the Archives of Ontario provide a wealth of material pertaining to business transactions at Montgomery's Inn from approximately 1830 until the mid 1850s. These paper, provided a source of information for the research paper entitled Thomas Montgomery, Portrait of a Nineteenth Century Gentleman, prepared by former staff members Carl Benn and Bev Hykel. That research paper was a major source of information for this article.

The second floor ballroom was most likely used for the Home District council meetings held in 1847 and 1849, as well as by the local and Grand Orange Lodge, which met there in the 1830s and 1840s. An Irish and Scottish potato famine relief fund was organized and administered from there in the 1840s.

During the surge, of patriotism that followed the Rebellion of 1837, Thomas obtained an officer's commission in the local militia, eventually rising to the rank of Captain. He may have even drilled his men on the property adjoining the inn.

Despite his prosperity, his family life, like many of his time, had its sadness. He and his wife, Margaret Dawson (1808-1855), had seven children, but only two sons survived to adulthood.

Robert (1837-1864) graduated from Victoria College, in Cobourg in 1857, and in the spring of 1859, enrolled at Trinity College in Toronto. In a letter dated 1860, he was addressed as Reverend R. A. Montgomery. Several letters survive, which provide insight into the lives and personalities of Robert, his wife Hannah, and his father Thomas Montgomery. Robert wrote to his father on August 7, 1862, expressing concern about his father's salvation. He wrote:

"...In conclusion Dear Father; I must say a word in reference to spiritual matters. We are all in the natural order of events approaching the end of life and whether we regard it or not, time is hurrying along and soon we shall all be called upon to resign this world and are we prepared for our change? If death should lay his iron grasp upon us what will be our prospects? Can we at that time look back with St. Paul and say "I have fought the good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith" and looking forward into eternity say "henceforth there is laid up for me a crown of righteousness which God the righteous judge will give me in that day and not to me only but unto all them also which love his appearing."

The way to obtain that blessing hope which animated St. Paul is easy first to know one's self; what are our bosom sins which we do not desire to forsake and see their heinousness in the sight of God, remembering that we cannot hide anything from God. Secondly, use repentance whereby we forsake sin and thirdly use faith everyday we rely on the promise of God; not a dead faith but faith which brings forth the works of love and thus we shall please God and be accepted of him. May this be our hope is the prayer of your affectionate son, Robert."

Thomas' response to this letter is not recorded. Thomas died on November 8, 1877 at the age of 87, and was buried from St. George's Anglican Church, Islington. He was interred in the Islington Burying Grounds on Dundas Street, west of Burnhamthorpe Road, where his wife and children were also buried.

Robert died in 1864, and his young son and namesake died the following year, leaving Hannah with two sons, Willie and Tom. This branch of the Montgomery family appeared to have been unpopular with the rest of the family and there were continued requests for financial assistance by Hannah for her children and by the children them-selves, as they grew older.

In 1865, Thomas wrote the following letter to his daughter-in-law Hannah, who has requested a yearly allowance from him:

"I cannot promise you any money is very Hard to be Got and For my part I have to Work as hard as Ever I had to do and Get very badly paid for it. Thanks be to God I have had Good health So as to make me to work for a living and Clothing I do not wish to become a Burden to any of my Friends as long as God will Grant me Good health so that I Can labour for a living..."

Thomas told her to manage her affairs well, and that she was lucky to get what she did in a pension from the church. He then, wished her a pleasant Christmas and a happy new year:

"...We are all enjoying Good health Thanks be to God for all his Blessings "Which he has bestowed on us... But I wish with all my heart that you May live well and prosper in your Deprived State and Be Thankful."

To us this seems to be an unbelievable response to his daughter-in-law and grandchildren. Thomas eventually did relent and sent Hannah $20.00, which he hoped would do some good. A few months later, in a letter dated March 20, 1866, Thomas committed himself to the only sentimental statement recorded about a member of his family, by saying that he was "very much cut down" since the death of his son, Robert.

Thomas' other son, William (1830-1920), however, and his, wife Jessie Douglas (1832-1915), and their family of ten children seemed to live an almost idyllic life, living in Briarly located on Dundas Street just east of Montgomery's Inn. William appears to have worked with his father until Thomas' death. He also managed his own business affairs, which included mortgage dealings and the management of his children's inheritances from Thomas' estate until they came of age. After his father's death, William, as executor, continued to administer the vast property holdings that his father had acquired during his lifetime.

William's family, with the exception of Charles, who was said to have been slow, was well educated. The daughters were enrolled at Rolleston House and the Brantford Young Ladies College. The sons received most of their secondary education at Upper Canada College. They eventually went into business, banking, medicine and law. On at least two occasions, some of the Montgomery siblings travelled to Europe, in one instance accompanied by their mother. In 1900, William and Jessie rented out Briarly and moved to 22 Isabella Street in Toronto, where they died.

Montgomery's Inn has been a landmark in Etobicoke for the past 173 years, and continues to serve the community. The appropriately-named Community Room, with 19th-century decor, provides a venue for community groups, clubs and private parties. Costumed volunteers serve afternoon tea Tuesday through Sunday. Special events are held regularly throughout the year.

Researched and Written by Randall Reid, Program Director, Montgomery's Inn (reprinted with permission from The York Pioneer, vol 99)

On the second floor, the public bedrooms show the common practice of renting a space in a bed, rather than a room or even an entire bed to an individual. It was not uncommon for two or three people to share a bed. The busiest time for innkeepers, including Thomas Montgomery, would be the winter months, when the farm population had the most leisure time, and the snow-covered, frozen roads were most favourable for travel. These travellers would probably welcome the opportunity to sleep in a bed with someone else in an attempt to keep warm!

The Thomas Montgomery Papers, deposited in the Baldwin Room of the Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library and the Archives of Ontario provide a wealth of material pertaining to business transactions at Montgomery's Inn from approximately 1830 until the mid 1850s. These paper, provided a source of information for the research paper entitled Thomas Montgomery, Portrait of a Nineteenth Century Gentleman, prepared by former staff members Carl Benn and Bev Hykel. That research paper was a major source of information for this article.

The second floor ballroom was most likely used for the Home District council meetings held in 1847 and 1849, as well as by the local and Grand Orange Lodge, which met there in the 1830s and 1840s. An Irish and Scottish potato famine relief fund was organized and administered from there in the 1840s.

During the surge, of patriotism that followed the Rebellion of 1837, Thomas obtained an officer's commission in the local militia, eventually rising to the rank of Captain. He may have even drilled his men on the property adjoining the inn.

Despite his prosperity, his family life, like many of his time, had its sadness. He and his wife, Margaret Dawson (1808-1855), had seven children, but only two sons survived to adulthood.

Robert (1837-1864) graduated from Victoria College, in Cobourg in 1857, and in the spring of 1859, enrolled at Trinity College in Toronto. In a letter dated 1860, he was addressed as Reverend R. A. Montgomery. Several letters survive, which provide insight into the lives and personalities of Robert, his wife Hannah, and his father Thomas Montgomery. Robert wrote to his father on August 7, 1862, expressing concern about his father's salvation. He wrote:

"...In conclusion Dear Father; I must say a word in reference to spiritual matters. We are all in the natural order of events approaching the end of life and whether we regard it or not, time is hurrying along and soon we shall all be called upon to resign this world and are we prepared for our change? If death should lay his iron grasp upon us what will be our prospects? Can we at that time look back with St. Paul and say "I have fought the good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith" and looking forward into eternity say "henceforth there is laid up for me a crown of righteousness which God the righteous judge will give me in that day and not to me only but unto all them also which love his appearing."

The way to obtain that blessing hope which animated St. Paul is easy first to know one's self; what are our bosom sins which we do not desire to forsake and see their heinousness in the sight of God, remembering that we cannot hide anything from God. Secondly, use repentance whereby we forsake sin and thirdly use faith everyday we rely on the promise of God; not a dead faith but faith which brings forth the works of love and thus we shall please God and be accepted of him. May this be our hope is the prayer of your affectionate son, Robert."

Thomas' response to this letter is not recorded. Thomas died on November 8, 1877 at the age of 87, and was buried from St. George's Anglican Church, Islington. He was interred in the Islington Burying Grounds on Dundas Street, west of Burnhamthorpe Road, where his wife and children were also buried.

Robert died in 1864, and his young son and namesake died the following year, leaving Hannah with two sons, Willie and Tom. This branch of the Montgomery family appeared to have been unpopular with the rest of the family and there were continued requests for financial assistance by Hannah for her children and by the children them-selves, as they grew older.

In 1865, Thomas wrote the following letter to his daughter-in-law Hannah, who has requested a yearly allowance from him:

"I cannot promise you any money is very Hard to be Got and For my part I have to Work as hard as Ever I had to do and Get very badly paid for it. Thanks be to God I have had Good health So as to make me to work for a living and Clothing I do not wish to become a Burden to any of my Friends as long as God will Grant me Good health so that I Can labour for a living..."

Thomas told her to manage her affairs well, and that she was lucky to get what she did in a pension from the church. He then, wished her a pleasant Christmas and a happy new year:

"...We are all enjoying Good health Thanks be to God for all his Blessings "Which he has bestowed on us... But I wish with all my heart that you May live well and prosper in your Deprived State and Be Thankful."

To us this seems to be an unbelievable response to his daughter-in-law and grandchildren. Thomas eventually did relent and sent Hannah $20.00, which he hoped would do some good. A few months later, in a letter dated March 20, 1866, Thomas committed himself to the only sentimental statement recorded about a member of his family, by saying that he was "very much cut down" since the death of his son, Robert.

Thomas' other son, William (1830-1920), however, and his, wife Jessie Douglas (1832-1915), and their family of ten children seemed to live an almost idyllic life, living in Briarly located on Dundas Street just east of Montgomery's Inn. William appears to have worked with his father until Thomas' death. He also managed his own business affairs, which included mortgage dealings and the management of his children's inheritances from Thomas' estate until they came of age. After his father's death, William, as executor, continued to administer the vast property holdings that his father had acquired during his lifetime.

William's family, with the exception of Charles, who was said to have been slow, was well educated. The daughters were enrolled at Rolleston House and the Brantford Young Ladies College. The sons received most of their secondary education at Upper Canada College. They eventually went into business, banking, medicine and law. On at least two occasions, some of the Montgomery siblings travelled to Europe, in one instance accompanied by their mother. In 1900, William and Jessie rented out Briarly and moved to 22 Isabella Street in Toronto, where they died.

Montgomery's Inn has been a landmark in Etobicoke for the past 173 years, and continues to serve the community. The appropriately-named Community Room, with 19th-century decor, provides a venue for community groups, clubs and private parties. Costumed volunteers serve afternoon tea Tuesday through Sunday. Special events are held regularly throughout the year.

Researched and Written by Randall Reid, Program Director, Montgomery's Inn (reprinted with permission from The York Pioneer, vol 99)