Highfield's Schools

In 1833, the government of Upper Canada hired John McVean and Elisha Lawrence to build a new east/west road across Etobicoke to give farmers coming from the northwest easier access to mills on the Humber River at Weston. Today we call that road Rexdale Boulevard, but before this it had many names: McVean’s Road (after John’s father, Alex), New Road, Gore Road, and Malton Rd.

As farmers began to use this new road, a small village grew up along the western end of Rexdale Blvd. with an inn, a blacksmith shop, a wagon maker, and a general store. It was named Highfield because it was on high ground above the wide valley of the West Humber River to the north. A Highfield post office opened there in 1866.

In 1841, the Common School Act was passed in Canada West (Ontario) and the province’s new Chief Superintendent, the Reverend Dr. Egerton Ryerson, appointed a commissioner in each township to initiate a new system of education. Etobicoke was divided into eight School Sections (S.S.), each managed by three government appointed trustees. Highfield was “S.S. No. 6” and, happily, was one of the few sections that made and preserved detailed records over the years, offering us a glimpse inside these early schools and showing us how much schools have changed since 1841.

The first school in Highfield was built in 1845 of logs on a small .035 acre lot donated by Joseph and Mary Ann Smith on the southeast corner of Rexdale Blvd. and Martin Grove Road. The first trustees were local farmers Joseph Smith, John Betteridge, and James Brooks. It is believed that first teacher was John Gardhouse, a local yeoman farmer who had been a school teacher in England.

Five generations of Gardhouses attended Highfield School, with 6 descendants becoming trustees through the years. Other well-known local family names appearing as trustees multiple times are Betteridge, Kellam, Bolton, Love, Avery, Cock, Middlebrook, Ross, Moody, Snead, Dixon, Gregory, Peters and Wardlaw.

Each school was given a large amount of autonomy, but was inspected regularly and was expected to hire trained teachers whenever possible. Families were required to pay a fee of 25 cents per month per child, but if they couldn’t afford that, they could contribute an equivalent amount in firewood. The fee was abolished in 1858 and schools were then funded from municipal taxes, just as they are today.

School attendance was made compulsory in 1846, and the school year was set at 11 months and seven days. Later the minimum number of days of attendance required annually was set at 100 to allow older boys time off to work on the family farm. Starting in 1881, truant officers were appointed to enforce this legislation. They collected fines from the parents of truants – often with difficulty. Eventually many truant officers found they had more success at improving attendance if they rounded up the truants themselves. In 1909, acknowledging the need for family labour on home farms during the summer, the September to June school year we have today was implemented.

In an 1850 report to Etobicoke’s Township Council, the school superintendent reported that Etobicoke had eight school sections, with 333 students, of which 214 could read and write, and 13 were learning French and Latin. The school buildings across the township were generally in good repair, except one that was a “mere hovel”.

Highfield School was fortunate to have desks and benches for the students as most log schools just had planks attached to the four walls for seats, with a second row of planks in front for desks. In the trustees’ book for January 1847, it is recorded that teacher William Lloyd received for his services “all that portion of the moneys allotted to School Section No. 6... together with three shillings, nine pence per quarter from the parents of each child in attendance.” Each child was also required to bring ¼ cord of wood, and a man was hired to chop it into small pieces to fit the stove. Included in the book was a list of the parents who could not afford these fees. Lloyd only stayed at Highfield School for half a year.

A few more examples from the trustees’ books demonstrate the high turnover in teachers in the early years. In October 1847, local farmer John Dixon was appointed as teacher with an annual salary of £53/15/8 and stayed five years. In January 1853, the trustees hired their first certified teacher, James Srigbey, at a salary of £62/5/10. He was a local leasehold farmer who had just graduated from the Methodist Model School in Newmarket, and he stayed 2 years. However, the next four teachers only stayed ½ year, 2 months, ½ year and 1 year.

The next teacher hired in 1859 was a local leasehold farmer and former trustee, William Hennel Black. There is some suggestion in the trustees’ notes that the school superintendent had granted Black a second class teaching certificate because it was “politically and educationally expedient” to recommend his fitness for the certificate in a time of shortage of qualified teachers. Black must have worked out because he taught in Highfield for the next seven years. But enrolment was growing, and in 1860, the Highfield School had a roster of 129 students aged five to 16. What a handful for one teacher in one room!

In 1840, a Roman Catholic school – believed to have been the first separate school built in rural Ontario - was erected just south of Highfield, about where Disco Road is today. When it closed in 1872, the enrolment at S.S. No. 6 increased significantly and the decision was made to build a larger school – although still of one room. In 1874, one acre of land was purchased for $150 from James and Ann Gardhouse on the west side of Highway 27, just south of Rexdale Blvd.

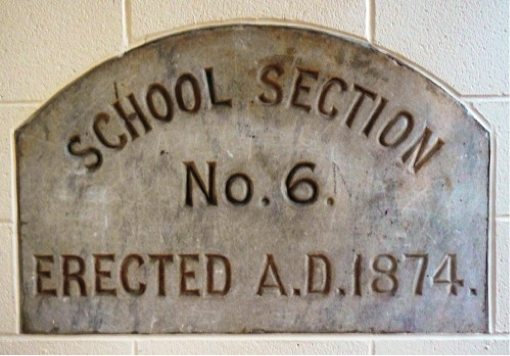

The new Highfield school embodied what we have come to think of as the classic “little red schoolhouse” - those stalwart little buildings with one room and one teacher that were the mainstay of our rural educational system for so many years. The school required 31,800 red bricks (at $6.75 per thousand) and 1,360 yellow bricks (at $10.00 per thousand). The total cost of the school was $1,789. It was heated with a cast iron stove, water was supplied from an outdoor well using a hand pump, and the bathrooms were outhouses. A plaque over the front door proclaimed “School Section No. 6 – Erected A.D. 1874”.

As farmers began to use this new road, a small village grew up along the western end of Rexdale Blvd. with an inn, a blacksmith shop, a wagon maker, and a general store. It was named Highfield because it was on high ground above the wide valley of the West Humber River to the north. A Highfield post office opened there in 1866.

In 1841, the Common School Act was passed in Canada West (Ontario) and the province’s new Chief Superintendent, the Reverend Dr. Egerton Ryerson, appointed a commissioner in each township to initiate a new system of education. Etobicoke was divided into eight School Sections (S.S.), each managed by three government appointed trustees. Highfield was “S.S. No. 6” and, happily, was one of the few sections that made and preserved detailed records over the years, offering us a glimpse inside these early schools and showing us how much schools have changed since 1841.

The first school in Highfield was built in 1845 of logs on a small .035 acre lot donated by Joseph and Mary Ann Smith on the southeast corner of Rexdale Blvd. and Martin Grove Road. The first trustees were local farmers Joseph Smith, John Betteridge, and James Brooks. It is believed that first teacher was John Gardhouse, a local yeoman farmer who had been a school teacher in England.

Five generations of Gardhouses attended Highfield School, with 6 descendants becoming trustees through the years. Other well-known local family names appearing as trustees multiple times are Betteridge, Kellam, Bolton, Love, Avery, Cock, Middlebrook, Ross, Moody, Snead, Dixon, Gregory, Peters and Wardlaw.

Each school was given a large amount of autonomy, but was inspected regularly and was expected to hire trained teachers whenever possible. Families were required to pay a fee of 25 cents per month per child, but if they couldn’t afford that, they could contribute an equivalent amount in firewood. The fee was abolished in 1858 and schools were then funded from municipal taxes, just as they are today.

School attendance was made compulsory in 1846, and the school year was set at 11 months and seven days. Later the minimum number of days of attendance required annually was set at 100 to allow older boys time off to work on the family farm. Starting in 1881, truant officers were appointed to enforce this legislation. They collected fines from the parents of truants – often with difficulty. Eventually many truant officers found they had more success at improving attendance if they rounded up the truants themselves. In 1909, acknowledging the need for family labour on home farms during the summer, the September to June school year we have today was implemented.

In an 1850 report to Etobicoke’s Township Council, the school superintendent reported that Etobicoke had eight school sections, with 333 students, of which 214 could read and write, and 13 were learning French and Latin. The school buildings across the township were generally in good repair, except one that was a “mere hovel”.

Highfield School was fortunate to have desks and benches for the students as most log schools just had planks attached to the four walls for seats, with a second row of planks in front for desks. In the trustees’ book for January 1847, it is recorded that teacher William Lloyd received for his services “all that portion of the moneys allotted to School Section No. 6... together with three shillings, nine pence per quarter from the parents of each child in attendance.” Each child was also required to bring ¼ cord of wood, and a man was hired to chop it into small pieces to fit the stove. Included in the book was a list of the parents who could not afford these fees. Lloyd only stayed at Highfield School for half a year.

A few more examples from the trustees’ books demonstrate the high turnover in teachers in the early years. In October 1847, local farmer John Dixon was appointed as teacher with an annual salary of £53/15/8 and stayed five years. In January 1853, the trustees hired their first certified teacher, James Srigbey, at a salary of £62/5/10. He was a local leasehold farmer who had just graduated from the Methodist Model School in Newmarket, and he stayed 2 years. However, the next four teachers only stayed ½ year, 2 months, ½ year and 1 year.

The next teacher hired in 1859 was a local leasehold farmer and former trustee, William Hennel Black. There is some suggestion in the trustees’ notes that the school superintendent had granted Black a second class teaching certificate because it was “politically and educationally expedient” to recommend his fitness for the certificate in a time of shortage of qualified teachers. Black must have worked out because he taught in Highfield for the next seven years. But enrolment was growing, and in 1860, the Highfield School had a roster of 129 students aged five to 16. What a handful for one teacher in one room!

In 1840, a Roman Catholic school – believed to have been the first separate school built in rural Ontario - was erected just south of Highfield, about where Disco Road is today. When it closed in 1872, the enrolment at S.S. No. 6 increased significantly and the decision was made to build a larger school – although still of one room. In 1874, one acre of land was purchased for $150 from James and Ann Gardhouse on the west side of Highway 27, just south of Rexdale Blvd.

The new Highfield school embodied what we have come to think of as the classic “little red schoolhouse” - those stalwart little buildings with one room and one teacher that were the mainstay of our rural educational system for so many years. The school required 31,800 red bricks (at $6.75 per thousand) and 1,360 yellow bricks (at $10.00 per thousand). The total cost of the school was $1,789. It was heated with a cast iron stove, water was supplied from an outdoor well using a hand pump, and the bathrooms were outhouses. A plaque over the front door proclaimed “School Section No. 6 – Erected A.D. 1874”.

The first teacher in the new school was Miss C. Buchanan, who earned $100/year. Teacher salaries varied over the years. In 1905, Miss Rowena Shaver was paid $300/year; when she left in 1909, her salary had increased to $475/year. Miss Donalda Woodill earned $700/year in 1915, a salary that remained stable until the 1940s.

Nelson Moody was born in Highfield in 1930 and attended the Highfield School from September 1936 to June 1945. Nelson’s great, great grandfather, John Moody, settled in the Highfield area in 1831, and three years later married Sarah Gardhouse. Many members of Nelson’s family attended this school before him, and he has kindly shared with me many photos and stories of Highfield.

Nelson recalls that in 1941, the students were thrilled when indoor bathrooms were installed – one on each side of the front door inside a new front porch. However, the school never had indoor plumbing, so the toilets emptied directly into pipes leading underground. Many a hat was lost down those pipes, thanks to student pranksters.

Nelson Moody was born in Highfield in 1930 and attended the Highfield School from September 1936 to June 1945. Nelson’s great, great grandfather, John Moody, settled in the Highfield area in 1831, and three years later married Sarah Gardhouse. Many members of Nelson’s family attended this school before him, and he has kindly shared with me many photos and stories of Highfield.

Nelson recalls that in 1941, the students were thrilled when indoor bathrooms were installed – one on each side of the front door inside a new front porch. However, the school never had indoor plumbing, so the toilets emptied directly into pipes leading underground. Many a hat was lost down those pipes, thanks to student pranksters.

During Nelson’s time at the school, wood for the school’s round cast iron stove was donated by one local farmer every year. At church on Sunday, there would be an announcement that all men were to gather at that farm the next week to cut wood for the year.

Nelson recalls that school caretaker, Bill McKnight, would drive his horse and wagon to the school early every morning, unlock the door, light the stove, wait for it to burn steadily, and refill the wood box. Then at 8:00 am he would head off to his regular job, working as a hired man for a local farmer. The teacher was responsible for adding wood and stoking the fire so it burned throughout the day. Then at about 6:00 pm, Bill would return to sweep the floor, take out the ashes, fill the stove with coal if it was winter to keep the stove warm overnight, and then lock up and go home.

After Nelson graduated from Grade 8, he attended Grade 9 at Weston Collegiate and Vocational School – the closest secondary school. He travelled to and from Weston by bicycle in the fall and spring, and by hitch-hiking in the winter - a 1½ to 2 hour trip each way!

Etobicoke’s population increased rapidly during the post-war Baby Boom, and in 1949 the Etobicoke Board of Education was formed. This new Board, with seven elected trustees, built larger schools across the township, which made the little red school houses redundant. The last teacher in S.S. No. 6, Mrs. Mildred V. Dix, oversaw its closure at Christmas in 1954. After that the children were bussed to school in Thistletown. The old school was demolished in 1957 when Highway 27 was widened.

In 1963, construction began two miles further north on the third school to bear the name “Highfield”. Highfield Junior School opened in January, 1964 at 85 Mount Olive Drive, and the plaque that was once mounted over the front door of the 1874 school is now mounted in the lobby of the 1964 school.

Nelson recalls that school caretaker, Bill McKnight, would drive his horse and wagon to the school early every morning, unlock the door, light the stove, wait for it to burn steadily, and refill the wood box. Then at 8:00 am he would head off to his regular job, working as a hired man for a local farmer. The teacher was responsible for adding wood and stoking the fire so it burned throughout the day. Then at about 6:00 pm, Bill would return to sweep the floor, take out the ashes, fill the stove with coal if it was winter to keep the stove warm overnight, and then lock up and go home.

After Nelson graduated from Grade 8, he attended Grade 9 at Weston Collegiate and Vocational School – the closest secondary school. He travelled to and from Weston by bicycle in the fall and spring, and by hitch-hiking in the winter - a 1½ to 2 hour trip each way!

Etobicoke’s population increased rapidly during the post-war Baby Boom, and in 1949 the Etobicoke Board of Education was formed. This new Board, with seven elected trustees, built larger schools across the township, which made the little red school houses redundant. The last teacher in S.S. No. 6, Mrs. Mildred V. Dix, oversaw its closure at Christmas in 1954. After that the children were bussed to school in Thistletown. The old school was demolished in 1957 when Highway 27 was widened.

In 1963, construction began two miles further north on the third school to bear the name “Highfield”. Highfield Junior School opened in January, 1964 at 85 Mount Olive Drive, and the plaque that was once mounted over the front door of the 1874 school is now mounted in the lobby of the 1964 school.

Today, this plaque and the pioneer Sharon Cemetery on Rexdale Blvd. are all that remain of old Highfield.

Researched and Written by Denise Harris

Researched and Written by Denise Harris