Grubb Farm "Elm Bank"

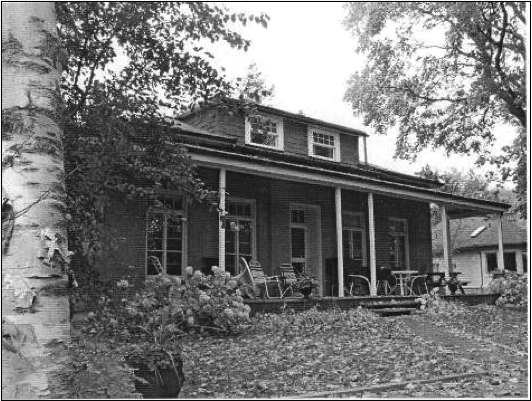

Hidden among the trees lining the West Branch of the Humber River off Islington Ave., less than two kilometers north of one of the world’s busiest freeways, stand two of Toronto’s oldest private homes, known together as Elm Bank. Although the property is well known within the neighbourhood of Old Thistletown, many residents of the wider city are often startled by their first sight of the old stone houses sitting undisturbed in their semi-pastoral setting. As the current owner of Elm Bank, I can attest that I am no longer eligible for pizza delivery orders “within 40 minutes or free” – the property is too difficult for the average driver to find!

It is this very isolation which I believe has enabled Elm Bank to survive in its original spot. The developers’ bull-dozers of the 1950s by-passed the immediate area, mainly because the land was already populated with summer cottages built in the early part of the 20th century. Indeed, in the 1920s and 30s Elm Bank was owned by a Montreal family who motored down each summer to enjoy swimming and salmon fishing in the Humber.

Much of what we know about the Grubbs comes from their letter-books and other records which passed into the hands of my grandfather Talbot. He augmented the records himself by visiting Scotland at least five times to research the Grubb origins. He began in 1906 (while visiting as a young member of the Argonaut Rowing Club) and over a period of fifty years compiled the various family trees, deciphering and then transcribing the many letters to and from Scotland, plus several local family letters. My grandfather’s work sat mostly undisturbed until 1987, when his daughter, my mother Janet, turned his type-written pages into book form, with a second edition following in 2001.

John Grubb is my great-great-great grandfather on the maternal side of my family. He was already fifty years of age when he arrived in Etobicoke with his wife and at least eight of his ten children in tow. Like many others, they had left Scotland because of the deepening economic depression – in John’s case he was having difficulties collecting the rents from his Edinburgh flats. He was by no means destitute, though. Family records suggest he was worth a comfortable ₤7500 on his arrival in 1833. Yet by the time of his death 17 years later, unfortunate circumstances would erode his wealth.

When the Grubbs arrived at their new homestead in August 1833, they took possession of the small stone house, still standing today. Dated between 1800 and 1820, it is one of the five oldest heritage buildings in Toronto. It’s unlikely that ten Grubbs would have fit into its three small bedrooms, so it is believed some of the family lived in a log house while a bigger stone house was being constructed just twenty feet away from the small stone house. Designed in the style of a Regency cottage, this is the house I live in today, while the older dwelling is a rental property. One of the relics I have inherited is an 1833 letter to John Grubb from Scotland, addressed “Lavinia Cottage, Township of Etobicoke, near York, Upper Canada”. The writer must be referring to Lavinia, the youngest of John’s children, who was just three years old in 1833. No one in my family has ever referred to the small house as anything but “the little house”. But I think it’s time to call it Lavinia Cottage, even though the reference might be to the temporary log house.

It is this very isolation which I believe has enabled Elm Bank to survive in its original spot. The developers’ bull-dozers of the 1950s by-passed the immediate area, mainly because the land was already populated with summer cottages built in the early part of the 20th century. Indeed, in the 1920s and 30s Elm Bank was owned by a Montreal family who motored down each summer to enjoy swimming and salmon fishing in the Humber.

Much of what we know about the Grubbs comes from their letter-books and other records which passed into the hands of my grandfather Talbot. He augmented the records himself by visiting Scotland at least five times to research the Grubb origins. He began in 1906 (while visiting as a young member of the Argonaut Rowing Club) and over a period of fifty years compiled the various family trees, deciphering and then transcribing the many letters to and from Scotland, plus several local family letters. My grandfather’s work sat mostly undisturbed until 1987, when his daughter, my mother Janet, turned his type-written pages into book form, with a second edition following in 2001.

John Grubb is my great-great-great grandfather on the maternal side of my family. He was already fifty years of age when he arrived in Etobicoke with his wife and at least eight of his ten children in tow. Like many others, they had left Scotland because of the deepening economic depression – in John’s case he was having difficulties collecting the rents from his Edinburgh flats. He was by no means destitute, though. Family records suggest he was worth a comfortable ₤7500 on his arrival in 1833. Yet by the time of his death 17 years later, unfortunate circumstances would erode his wealth.

When the Grubbs arrived at their new homestead in August 1833, they took possession of the small stone house, still standing today. Dated between 1800 and 1820, it is one of the five oldest heritage buildings in Toronto. It’s unlikely that ten Grubbs would have fit into its three small bedrooms, so it is believed some of the family lived in a log house while a bigger stone house was being constructed just twenty feet away from the small stone house. Designed in the style of a Regency cottage, this is the house I live in today, while the older dwelling is a rental property. One of the relics I have inherited is an 1833 letter to John Grubb from Scotland, addressed “Lavinia Cottage, Township of Etobicoke, near York, Upper Canada”. The writer must be referring to Lavinia, the youngest of John’s children, who was just three years old in 1833. No one in my family has ever referred to the small house as anything but “the little house”. But I think it’s time to call it Lavinia Cottage, even though the reference might be to the temporary log house.

The Grubb letters do not give specific dates or details on the building of the large house at Elm Bank, nor about a second stone house built on the other side of Albion Rd (on the same Lot 30) to be named Brae Burn. But it seems reasonable that work was completed on the large house in 1834 or 35. Brae Burn was built between 1835 and 1850, about a ten minute walk from Elm Bank.

John acquired a third parcel of land north of Elm Bank right in the village of St Andrews, re-named Thistletown in about 1867 after the local physician, Dr. Thistle. Apparently the Grubbs were unhappy with the name change, since John had named St Andrews after the place of his birth. I’ve always wondered if the family had ever lobbied for the name of “Grubbtown”, but it’s no surprise that name was never suggested. (There is, however, a small street near Islington and Albion named John Grubb Court.)

John acquired a third parcel of land north of Elm Bank right in the village of St Andrews, re-named Thistletown in about 1867 after the local physician, Dr. Thistle. Apparently the Grubbs were unhappy with the name change, since John had named St Andrews after the place of his birth. I’ve always wondered if the family had ever lobbied for the name of “Grubbtown”, but it’s no surprise that name was never suggested. (There is, however, a small street near Islington and Albion named John Grubb Court.)

Whilst John’s wife and children were busy establishing the Elm Bank and Brae Burn farms in the 1830s, John made several trips back to Edinburgh to check on his properties, consisting of 200 rental flats. (The buildings still exist, and can be viewed on the Google Maps website.) Today we complain about airline delays, but back then a trip from Etobicoke to Scotland could take two months; John might have been away for up to half a year at a time, wisely absenting himself from the Canadian winters. As for the Mackenzie Rebellion of 1837, John made his opinions known through letters back to Scotland. An excerpt from December 1838 to his brother-in-law in Edinburgh:

“You will have seen by the newspapers that an attempt at independence was made by the people of these provinces. It was certainly commenced at an improper time. The Canadas [East & West] never could expect to contend with Britain when she is at peace with the world. I impute the whole cause of the disturbance in the Upper Province to the Tory principles of Sir F.B. Head [Lt-Governor Francis Bond Head] and his Council. It has done a great deal of mischief in the meantime to the Colonies and we have some hope the Earl of Durham will act upon different principles although in the meantime he has a good deal dispirited me in not acting at once as generously with the Upper Province Patriots or Rebels as with the Lower Province. I took no part in the struggle on either side and of course have not been annoyed very much. Very liberal principles must be introduced or the expense of keeping the Colonies, I believe, will be more than I should think the people in Britain will be willing to pay or in fact than they are worth.”

In a later letter, John referred to Lt-Governors Sir John Colborne as “the Old Woman” and Bond Head as “The Mountebank”, and said that only the release of Lord Durham’s report kept him from abandoning Etobicoke for the United States. So we know where his sympathies lay. His brother William was already established in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., where three of John’s daughters eventually moved after their marriages in the 1840s – Isabella, Eliza and Lavinia. The eldest daughter James Ann (known as Jamima) probably never resided at Elm Bank but went straight with her younger brother Walter to Colchester, near Point Pelee, where John had acquired 200 acres. William, the eldest, would inherit Elm Bank; Robert lived at Elm Bank and later at Brae Burn until 1890, having never married; and John (Jr.) apparently made his way to the mid-western United States in the 1840s. He achieved some success in St. Louis Mo., then married and settled in New Orleans, La. But he was struck down along with his wife by yellow fever in 1847 at the age of 31. His portrait hangs in my living room. Two more of John’s children died the same year – Jamima in Colchester at age 38 and Isabella in Poughkeepsie at age 26. John Grubb was by now 64 years old. In addition to these heartbreaks, he and his wife had lost their first two children in infancy back in Scotland. They outlived five of their twelve children. His letters mention the later deaths but not the causes, and he bears the tragedies with typical Scots stoicism.

Another daughter, Jessie, according to her father “the best looking and best tempered”, left in 1845 to join her brother John in the U.S. She is the only Grubb pioneer with no recorded date of death. The youngest son, Andrew, was the chief tenant of Brae Burn until his father’s passing in 1850, when he inherited the property. Since William inherited Elm Bank as the eldest son, it seems curious that Robert was not bequeathed any property, whilst his two younger brothers inherited the Brae Burn and Colchester farms. Of ten beneficiaries, John Grubb’s will left property or at least ₤500 to everyone except Robert, who received only ₤100 in trust. To top off the disparity, his brothers received the entire estate residue – Robert was excluded. None of John’s letters suggest any displeasure with Robert, and Robert’s own letters, which form a large part of the post 1850 correspondence, betray no family disruptions. He does not appear to have been independently wealthy. His sins, if any, might have been his lack of involvement in farming, politics or road-making, or not finding a wife.

Farming was not always profitable for the Grubbs, due partly to the “wretched” state of provincial roads. Moving produce and flour from the Humber mills over the rutted paths to market in Toronto was arduous and hazardous. John Grubb believed that “public-spirited gentlemen”, rather than governing authorities, should remedy transit problems and so in 1841 he organized the Weston Plank Road Co. Inc. with six local residents. It was capitalized at ₤3,500, with 2¼ million feet of pine plank and three toll gates. Five years later, John organized the Albion Plank Road Co. which connected to the Weston toll road and ran several miles west to Claireville, with a spin-off road to Kleinburg. But by the early 1850s, the advent of the railways plus the prohibitive cost of road upkeep sucked all profit out of the enterprise, and the companies were wound up by 1870. The Plank Road building on Weston Rd where the Grubbs and others managed the business still stands (about a minute’s drive south of the 401). Designated in 1987 under the Ontario Heritage Act, the place was boarded up for several years, and though some renovations have been done recently it is still empty with a forlorn appearance. It is currently owned by a numbered company.

“You will have seen by the newspapers that an attempt at independence was made by the people of these provinces. It was certainly commenced at an improper time. The Canadas [East & West] never could expect to contend with Britain when she is at peace with the world. I impute the whole cause of the disturbance in the Upper Province to the Tory principles of Sir F.B. Head [Lt-Governor Francis Bond Head] and his Council. It has done a great deal of mischief in the meantime to the Colonies and we have some hope the Earl of Durham will act upon different principles although in the meantime he has a good deal dispirited me in not acting at once as generously with the Upper Province Patriots or Rebels as with the Lower Province. I took no part in the struggle on either side and of course have not been annoyed very much. Very liberal principles must be introduced or the expense of keeping the Colonies, I believe, will be more than I should think the people in Britain will be willing to pay or in fact than they are worth.”

In a later letter, John referred to Lt-Governors Sir John Colborne as “the Old Woman” and Bond Head as “The Mountebank”, and said that only the release of Lord Durham’s report kept him from abandoning Etobicoke for the United States. So we know where his sympathies lay. His brother William was already established in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., where three of John’s daughters eventually moved after their marriages in the 1840s – Isabella, Eliza and Lavinia. The eldest daughter James Ann (known as Jamima) probably never resided at Elm Bank but went straight with her younger brother Walter to Colchester, near Point Pelee, where John had acquired 200 acres. William, the eldest, would inherit Elm Bank; Robert lived at Elm Bank and later at Brae Burn until 1890, having never married; and John (Jr.) apparently made his way to the mid-western United States in the 1840s. He achieved some success in St. Louis Mo., then married and settled in New Orleans, La. But he was struck down along with his wife by yellow fever in 1847 at the age of 31. His portrait hangs in my living room. Two more of John’s children died the same year – Jamima in Colchester at age 38 and Isabella in Poughkeepsie at age 26. John Grubb was by now 64 years old. In addition to these heartbreaks, he and his wife had lost their first two children in infancy back in Scotland. They outlived five of their twelve children. His letters mention the later deaths but not the causes, and he bears the tragedies with typical Scots stoicism.

Another daughter, Jessie, according to her father “the best looking and best tempered”, left in 1845 to join her brother John in the U.S. She is the only Grubb pioneer with no recorded date of death. The youngest son, Andrew, was the chief tenant of Brae Burn until his father’s passing in 1850, when he inherited the property. Since William inherited Elm Bank as the eldest son, it seems curious that Robert was not bequeathed any property, whilst his two younger brothers inherited the Brae Burn and Colchester farms. Of ten beneficiaries, John Grubb’s will left property or at least ₤500 to everyone except Robert, who received only ₤100 in trust. To top off the disparity, his brothers received the entire estate residue – Robert was excluded. None of John’s letters suggest any displeasure with Robert, and Robert’s own letters, which form a large part of the post 1850 correspondence, betray no family disruptions. He does not appear to have been independently wealthy. His sins, if any, might have been his lack of involvement in farming, politics or road-making, or not finding a wife.

Farming was not always profitable for the Grubbs, due partly to the “wretched” state of provincial roads. Moving produce and flour from the Humber mills over the rutted paths to market in Toronto was arduous and hazardous. John Grubb believed that “public-spirited gentlemen”, rather than governing authorities, should remedy transit problems and so in 1841 he organized the Weston Plank Road Co. Inc. with six local residents. It was capitalized at ₤3,500, with 2¼ million feet of pine plank and three toll gates. Five years later, John organized the Albion Plank Road Co. which connected to the Weston toll road and ran several miles west to Claireville, with a spin-off road to Kleinburg. But by the early 1850s, the advent of the railways plus the prohibitive cost of road upkeep sucked all profit out of the enterprise, and the companies were wound up by 1870. The Plank Road building on Weston Rd where the Grubbs and others managed the business still stands (about a minute’s drive south of the 401). Designated in 1987 under the Ontario Heritage Act, the place was boarded up for several years, and though some renovations have been done recently it is still empty with a forlorn appearance. It is currently owned by a numbered company.

In addition to his farming and toll road businesses, John Grubb took on duties as an elected Magistrate and District Councillor for the new Etobicoke District. He was elected for three terms, along with J.W. Gamble, from 1844 to 1846. Grubb’s record book of his judicial cases is still in the possession of Grubb descendants. (The other Letter and Account books are in the Ontario and Toronto Archives). Many entries show that St. Andrew’s, population about 100, was not crime free. Forty cases are listed for 1844 alone, several of them involving the tavern keeper Mr. Conat either as a witness, plaintiff or defendant. (St. Andrew’s was first known variously as Coonat’s, Conat’s or Conant’s Corners.) Many cases involved trespass, since property lines were anything but exact, or wage disputes. There were several incidents of assault and battery, including the example below:

April 4th, 1844. № 5. Thos. Wheeler vs. Cairns.

Assault and battery

John Eagle (sworn witness):

Cairns said to Wheeler that he owed him three dollars. Wheeler called Cairns a liar, took an axe handle, struck at Cairns. When Cairns laid hold of Wheeler a scuffle ensued. Wheeler ordered Cairns out of the house, would not go, Wheeler took up a hoe to force him out.

The defendant was ordered to pay costs of 11 shillings and the matter was “settled”. Most of the cases involved fines of two pounds or less.

After John Grubb’s death at Elm Bank in 1850 (his wife Janet died twelve years later, also at Elm Bank), his son William took over the businesses. His brother Andrew was residing at Brae Burn with his sister Eliza and her husband. Robert’s letters, notes and poems start to appear in the letter book at this time, including a vivid description of Brae Burn’s destruction by fire in 1852. The house “went up like a roll of tow”, but everyone survived. Andrew decided to rebuild, which Robert writes “took longer than Solomon’s Temple to finish”. The result was a fine sturdy residence, larger than Elm Bank, costing £186. Andrew, however, enjoyed the new house only another six years, dying at age 35. No cause of death is recorded in my grandfather’s notes. That left William, Robert and Jessie remaining at Elm Bank and Brae Burn.

No further entries were made in the Grubb account books after 1870, the same time that the Plank Road business was wound up. Around this time, the letter “e” was added to the Grubb name by William; no one ventured a reason why. One possible theory is at one time people would add an ‘e’ to their surnames in an effort to anglicize them.

William and his wife Mary had a son in 1846, also named William Charles Grubbe - the same name as his father and great uncle in Colchester. He met his future wife Charlotte Cornwall whilst visiting Uncle Walter in Poughkeepsie in 1867. He was 21, Charlotte 14. They waited until she was 21 for the marriage, and then came to live at Brae Burn in 1875. By 1890, though, with the death of Willie’s father William, the family’s financial fortunes forced the sale of Elm Bank to the Barker family, and the mortgaging of Brae Burn. As my grandfather wrote, “John Grubb’s generosity to his children [most of them] and the losses on the Edinburgh properties, the two road companies and the depressed state of agriculture left very little to pay the debts.” William and Charlotte’s marriage lasted 59 years and, according to my mother, “Willie and Charlie” doted upon each other. They died in 1934, just three weeks apart, and were buried in the Grubbe plot in St. Philip’s Churchyard. A memorial stained glass window was dedicated the following year to their memory, and William’s name was inscribed on the church bell in honour of his long-time service as church warden. A second stained glass window was dedicated in 1968 by their Grubbe descendants in memory of William and Charlotte’s five children (seen in Figure 4).

April 4th, 1844. № 5. Thos. Wheeler vs. Cairns.

Assault and battery

John Eagle (sworn witness):

Cairns said to Wheeler that he owed him three dollars. Wheeler called Cairns a liar, took an axe handle, struck at Cairns. When Cairns laid hold of Wheeler a scuffle ensued. Wheeler ordered Cairns out of the house, would not go, Wheeler took up a hoe to force him out.

The defendant was ordered to pay costs of 11 shillings and the matter was “settled”. Most of the cases involved fines of two pounds or less.

After John Grubb’s death at Elm Bank in 1850 (his wife Janet died twelve years later, also at Elm Bank), his son William took over the businesses. His brother Andrew was residing at Brae Burn with his sister Eliza and her husband. Robert’s letters, notes and poems start to appear in the letter book at this time, including a vivid description of Brae Burn’s destruction by fire in 1852. The house “went up like a roll of tow”, but everyone survived. Andrew decided to rebuild, which Robert writes “took longer than Solomon’s Temple to finish”. The result was a fine sturdy residence, larger than Elm Bank, costing £186. Andrew, however, enjoyed the new house only another six years, dying at age 35. No cause of death is recorded in my grandfather’s notes. That left William, Robert and Jessie remaining at Elm Bank and Brae Burn.

No further entries were made in the Grubb account books after 1870, the same time that the Plank Road business was wound up. Around this time, the letter “e” was added to the Grubb name by William; no one ventured a reason why. One possible theory is at one time people would add an ‘e’ to their surnames in an effort to anglicize them.

William and his wife Mary had a son in 1846, also named William Charles Grubbe - the same name as his father and great uncle in Colchester. He met his future wife Charlotte Cornwall whilst visiting Uncle Walter in Poughkeepsie in 1867. He was 21, Charlotte 14. They waited until she was 21 for the marriage, and then came to live at Brae Burn in 1875. By 1890, though, with the death of Willie’s father William, the family’s financial fortunes forced the sale of Elm Bank to the Barker family, and the mortgaging of Brae Burn. As my grandfather wrote, “John Grubb’s generosity to his children [most of them] and the losses on the Edinburgh properties, the two road companies and the depressed state of agriculture left very little to pay the debts.” William and Charlotte’s marriage lasted 59 years and, according to my mother, “Willie and Charlie” doted upon each other. They died in 1934, just three weeks apart, and were buried in the Grubbe plot in St. Philip’s Churchyard. A memorial stained glass window was dedicated the following year to their memory, and William’s name was inscribed on the church bell in honour of his long-time service as church warden. A second stained glass window was dedicated in 1968 by their Grubbe descendants in memory of William and Charlotte’s five children (seen in Figure 4).

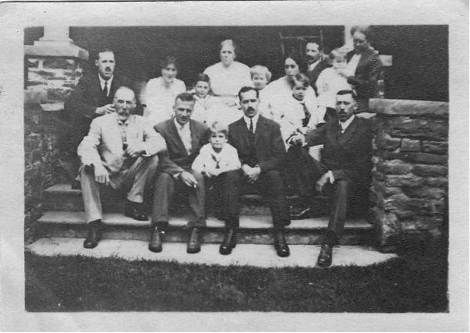

Figure 4: Grubbes on steps at Brae Burn c. 1927. Patriarch William is front left, wife Charlotte middle rear. Their five children plus five of eight grandchildren are here, including Evelyn at top right. My grandfather Talbot is at top left, with brothers l-r George, Roaf and Charles, and his sister Helen to the left of Charlotte (with child on her lap).

In 1942, eight years after William’s death, Brae Burn was sold to the Ballard family (of the pet food name) for $10,000. Only sheer good luck and timing prevented Brae Burn from being bull-dozed into oblivion in 1963. There are no photos or records of the event, but Brae Burn’s two-foot thick stone walls were taken apart and reassembled along with the rest of the house at Black Creek Pioneer Village. The cost was $50,000, according to Evelyn Grubbe (Mickie), who was the last Grubbe to have lived at Brae Burn. She passed away in 2009.)

Brae Burn’s rebirth at Pioneer Village was a happy event for the Grubbe descendants. The house was deemed serviceable enough to become the home of the Village Superintendent. When the incumbent Super left in the early 2000s, the house became vacant and, like the Plank Rd building, was boarded up. But good fortune returned in 2002 when the Toronto Region Conservation Authority leased eight acres of land, including the Brae Burn site, to the City of Toronto’s Parks & Forestry Division. Since 2007, the house and land have been used as part of Toronto’s Urban Farm project, where youth from the nearby communities, many of whom are downtrodden and stigmatized, are trained in urban organic farming each summer. Brae Burn House is now used as an office and training space where leadership development is provided annually to two dozen or so youths. The house was officially opened by Councillor Maria Augimeri in 2007 (see Figure 6). Remarkably, after being nearly written off twice, Brae Burn is back in the farming business. Both John and William Grubb would no doubt approve; William in particular actively supported housing and employment initiatives for the newly arrived Irish who struggled to gain a foothold in Toronto in the 1840s. While not generally accessible to the public, Brae Burn house can be seen on the east side of Jane St., just south of Steeles.

Brae Burn’s rebirth at Pioneer Village was a happy event for the Grubbe descendants. The house was deemed serviceable enough to become the home of the Village Superintendent. When the incumbent Super left in the early 2000s, the house became vacant and, like the Plank Rd building, was boarded up. But good fortune returned in 2002 when the Toronto Region Conservation Authority leased eight acres of land, including the Brae Burn site, to the City of Toronto’s Parks & Forestry Division. Since 2007, the house and land have been used as part of Toronto’s Urban Farm project, where youth from the nearby communities, many of whom are downtrodden and stigmatized, are trained in urban organic farming each summer. Brae Burn House is now used as an office and training space where leadership development is provided annually to two dozen or so youths. The house was officially opened by Councillor Maria Augimeri in 2007 (see Figure 6). Remarkably, after being nearly written off twice, Brae Burn is back in the farming business. Both John and William Grubb would no doubt approve; William in particular actively supported housing and employment initiatives for the newly arrived Irish who struggled to gain a foothold in Toronto in the 1840s. While not generally accessible to the public, Brae Burn house can be seen on the east side of Jane St., just south of Steeles.

It’s not just today’s Brae Burn that has returned to farming; a piece of the original Brae Burn property cultivated by “Willie” Grubb is still in use as a working farm. Known as Anga’s Farm, it is located about 500 metres east of Elm Bank and features a full commercial Garden Centre. It is the last working farm existing in Toronto.

Although Elm Bank was sold by the Grubbes in 1890, it was never forgotten by the family. My grandfather Talbot, who was President of the York Pioneers for three years in the late 1940s, kept in contact with the Mayall family, owners of Elm Bank since the 1940s. His death at age 82 in 1965 might have marked the end of the Grubbe contact with the old homestead. But in 1972, Elm Bank returned to family’s hands after Talbot’s daughter Kay (Ouchterlony) saw a real estate ad indicating the Mayalls were selling. In short order, my aunt Kay and my mother convinced their 86-year-old mother Meg to invest in Elm Bank for family posterity.

Although Elm Bank was sold by the Grubbes in 1890, it was never forgotten by the family. My grandfather Talbot, who was President of the York Pioneers for three years in the late 1940s, kept in contact with the Mayall family, owners of Elm Bank since the 1940s. His death at age 82 in 1965 might have marked the end of the Grubbe contact with the old homestead. But in 1972, Elm Bank returned to family’s hands after Talbot’s daughter Kay (Ouchterlony) saw a real estate ad indicating the Mayalls were selling. In short order, my aunt Kay and my mother convinced their 86-year-old mother Meg to invest in Elm Bank for family posterity.

Various relatives rented the two houses at different times. I came along in 1975, just out of university and intending to “crash” at Elm Bank for a few months as I began my working career. But Elm Bank cast its spell on me and I’ve never left. When grandmother Meg died in 1979, I continued to rent from my mother and aunt (and uncle David Grubbe) until 1984, when I purchased the big house. I will never forget the date – mortgage rates were 14% and I was grateful for a “family discount”. The little house, Lavinia Cottage, continues to be rented out, alleviating the considerable expense of maintaining an old property. I have since bought the interest in the little house from the various estates of my mother, aunt and uncle.

Until recently, I felt no need to use outside authority to protect Elm Bank, as I am not the type to disrespect heritage homes by throwing up aluminum siding or paving the front yard. But as I do not anticipate immortality, I recently began to explore designating Elm Bank under the Ontario Heritage Act. Beginning in February 2007, the process wasn’t completed until August 2008, when City Council passed the by-law. History-challenged future owners might still try to flatten Elm Bank, but at least now they would encounter a legal obstacle.

A Heritage designation means that every five years I am eligible to receive a grant of up to $10,000 to help maintain the exteriors of the two houses. Even though the process was labour-intensive and drawn out to 18 months, I was able to obtain a grant to restore the five biggest original wood windows on Lavinia Cottage.

I have lived at Elm Bank since 1975. It’s an oasis in the city, made special by my ancestors’ courage and perseverance.

Until recently, I felt no need to use outside authority to protect Elm Bank, as I am not the type to disrespect heritage homes by throwing up aluminum siding or paving the front yard. But as I do not anticipate immortality, I recently began to explore designating Elm Bank under the Ontario Heritage Act. Beginning in February 2007, the process wasn’t completed until August 2008, when City Council passed the by-law. History-challenged future owners might still try to flatten Elm Bank, but at least now they would encounter a legal obstacle.

A Heritage designation means that every five years I am eligible to receive a grant of up to $10,000 to help maintain the exteriors of the two houses. Even though the process was labour-intensive and drawn out to 18 months, I was able to obtain a grant to restore the five biggest original wood windows on Lavinia Cottage.

I have lived at Elm Bank since 1975. It’s an oasis in the city, made special by my ancestors’ courage and perseverance.

An Old Family Photo Gets a New Life

On a visit by my cousin Charlotte Mickie last summer to Elm Bank, my 1834 Thistletown home built by our maternal Scots ancestors, she pointed out the 4” by 5” photo portrait of our great, great grandfather William Grubb which had been hanging for years, half forgotten, in a dark corner of the living room. We both knew that it was a daguerrotype, an example of the very first photographic process. Made of silver plate bonded to copper, they first appeared in North America in the early 1840s, peaked in the 1850s, and gave way in the 1860s to other photographic processes.

“Why don’t you look at getting Willie fixed up? I know someone who might do it,” suggested Charlotte. We feel it’s OK to call him Willie because that’s what his father called his own son in letters that still survive. The damage and wear and tear from over 150 years of hanging around are evident in the photo at the left, above. I agreed to have Charlotte get Willie looked at by Mike Robinson at Mike’s Century Darkroom in Toronto. We were skeptical that the large stain in the middle of the photo could be removed but, within a few months, back came the stunning restoration, seen above right. When viewed online, the “dag” is almost as clear as a modern digital camera shot.

In much clearer relief behind Willie can be seen a portrait of his father John, who had died in 1850, most likely before “Dags” were available. So it seems this photo was Willie’s way of honouring his father and leaving a remembrance. Mr. Robinson dates the photo from the early to mid 1850s. He can’t identify the studio, but believes it was taken in southwestern Ontario.

On a visit by my cousin Charlotte Mickie last summer to Elm Bank, my 1834 Thistletown home built by our maternal Scots ancestors, she pointed out the 4” by 5” photo portrait of our great, great grandfather William Grubb which had been hanging for years, half forgotten, in a dark corner of the living room. We both knew that it was a daguerrotype, an example of the very first photographic process. Made of silver plate bonded to copper, they first appeared in North America in the early 1840s, peaked in the 1850s, and gave way in the 1860s to other photographic processes.

“Why don’t you look at getting Willie fixed up? I know someone who might do it,” suggested Charlotte. We feel it’s OK to call him Willie because that’s what his father called his own son in letters that still survive. The damage and wear and tear from over 150 years of hanging around are evident in the photo at the left, above. I agreed to have Charlotte get Willie looked at by Mike Robinson at Mike’s Century Darkroom in Toronto. We were skeptical that the large stain in the middle of the photo could be removed but, within a few months, back came the stunning restoration, seen above right. When viewed online, the “dag” is almost as clear as a modern digital camera shot.

In much clearer relief behind Willie can be seen a portrait of his father John, who had died in 1850, most likely before “Dags” were available. So it seems this photo was Willie’s way of honouring his father and leaving a remembrance. Mr. Robinson dates the photo from the early to mid 1850s. He can’t identify the studio, but believes it was taken in southwestern Ontario.

So a thank you to my cousin Charlotte who brought our ancestors William and John Grubb back into much clearer view. After I had happily put the re-framed photo back on its hook on the wall, within half an hour I heard a rustling and a thud from the other room. Expecting to find Willie and John broken on the wood floor, instead the photo had somehow wedged itself at an angle, suspended against another portrait of John Grubb lower down the wall. Surely this means that the Grubbs, who built and lived at Elm Bank so long ago, approve of their restoration.

Researched and Written by Michael Fitzgerald

From the Author: [Sources include material drawn from my grandfather’s writings and research from 1906-1954, which my mother Janet FitzGerald compiled as the book “The Grubb Pioneers of Etobicoke” (1987; 2nd edition 2001, Pro Familia). All photos are from the author’s collection.]