Bais-Oilom

At the end of the 19th century, immigrant Jews, most of whom were from Poland and Russia, settled in “The Junction” area of Toronto. They were attracted by the employment and business opportunities afforded by the area’s intersecting railways. Maria Street quickly became a thriving enclave for Jews. In 1909, the Congregation Knesseth Israel was founded, holding their first services in a home at 303 Maria Street.

On November 25, 1910, this new congregation also established a Bais-Oilom, translated literally as a “House of the World”, a euphemism for cemetery.

They bought a six-acre piece of land on the east side of Church Street (now Royal York Road), just north of to-day’s Edenbridge Drive. The lot was purchased from Thomas and Mary Jane Bethell, Irish immigrants who had been market gardeners on the land for several years. The west two thirds along Royal York Road was high land, while the east one third sloped down to a much lower level.

The Burial Committee for the Knesseth Israel congregation administered the cemetery, which was considered to be an essential component in the proper functioning of a synagogue, also called a shul. Members of the shul, each paying monthly dues, were entitled to a cemetery plot and a cost-free burial service. The cemetery was also used to bury sacred religious artifacts. For example, in the 1920s, a fire damaged part of this congregation’s sacred Torah, the scroll which outlines the laws on which Judaism is based. The burnt sections were gathered together and buried in the cemetery.

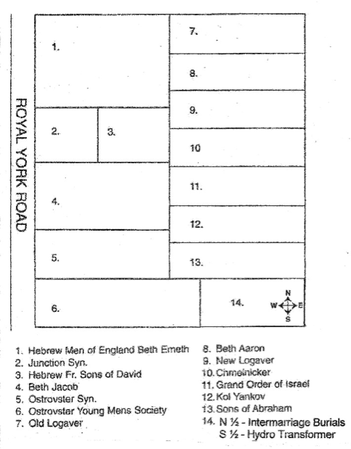

On March 3, 1911, the Burial Committee sold one acre in the northwest corner of their property to the Hebrew Men of England Congregation for $425. Over the years, other sections of the cemetery were sold to other congregations, so today Lambton Mills Cemetery is actually 14 different small cemeteries (see map below), all maintained by the Roselawn Lambton Cemetery Association.

They bought a six-acre piece of land on the east side of Church Street (now Royal York Road), just north of to-day’s Edenbridge Drive. The lot was purchased from Thomas and Mary Jane Bethell, Irish immigrants who had been market gardeners on the land for several years. The west two thirds along Royal York Road was high land, while the east one third sloped down to a much lower level.

The Burial Committee for the Knesseth Israel congregation administered the cemetery, which was considered to be an essential component in the proper functioning of a synagogue, also called a shul. Members of the shul, each paying monthly dues, were entitled to a cemetery plot and a cost-free burial service. The cemetery was also used to bury sacred religious artifacts. For example, in the 1920s, a fire damaged part of this congregation’s sacred Torah, the scroll which outlines the laws on which Judaism is based. The burnt sections were gathered together and buried in the cemetery.

On March 3, 1911, the Burial Committee sold one acre in the northwest corner of their property to the Hebrew Men of England Congregation for $425. Over the years, other sections of the cemetery were sold to other congregations, so today Lambton Mills Cemetery is actually 14 different small cemeteries (see map below), all maintained by the Roselawn Lambton Cemetery Association.

In 1911, the Knesseth Israel congregation bought a lot on Maria Street on the northeast corner of Shipman Street for $520 and built their new shul. The Knesseth Israel Shul was designed by well-known Junction architect James A. Ellis. Commonly known as the “Junction Shul”, it was paid for over time by donations from the founding families. After its dedication on September 8, 1912, this new synagogue was the impetus for a dramatic increase in the number of Jews moving into the Junction area, peaking at 200 families in the 1920s.

However, after World War II, Jewish residents began to move out of the Junction and in 1950, the shul was forced to limit its services to high holidays only. Knesseth Israel today is Toronto’s oldest active synagogue in its original location. Descendants of founding members still care for this building and share in the benefits of its Bais-Oilom.

Because most of Lambton Mills Cemetery is atop a hill, it is barely visible to passers-by on Royal York Road. A long, unpaved driveway leads up from the street to the western cemetery entrances. Another lane runs east along the south side of the cemetery.

Because most of Lambton Mills Cemetery is atop a hill, it is barely visible to passers-by on Royal York Road. A long, unpaved driveway leads up from the street to the western cemetery entrances. Another lane runs east along the south side of the cemetery.

In 1966, 400 people gathered in Section 6 of the cemetery to unveil a striking black granite memorial to Jews killed by Nazis at Ostrovietz, Poland, between 1941 and 1945. This monument is 12 feet high and covered with the names of hundreds of murdered families. In 1999, the monument was damaged when vandals sprayed it with blatant racial slurs in blue paint. Tony Duguid, a Mohawk art restorer from the Six Nations, voluntarily helped restore this monument and it still occupies a restful, shady spot in the Ostrovster Synagogue section.

One of this cemetery’s most famous interments is athlete and sports writer Fannie “Bobbie” Rosenfeld. Born in Russia in 1904, her family settled in Barrie, Ontario, when she was an infant. In 1922, they moved to Toronto where Bobbie joined the Young Women’s Hebrew Association. Her prowess in track and field, hockey, softball and basketball quickly developed. She competed in the 1928 Olympics, winning gold and silver medals. After earning many other awards, arthritis forced her retirement in 1933. After that, she wrote a spirited sports column for the Globe & Mail for over 20 years. In 1950, Bobbie was named Canada’s female athlete of the half-century. She was inducted into the Sports Hall of Fame and a stamp was issued in her honour. She died in 1959 and was buried in Lambton Mills Cemetery where her parents, Max and Sarah, were already interred.

Lambton Mills is one of the few Jewish cemeteries in the world that will permit a non-Jewish person to be buried with their Jewish spouse. In 2008, Toronto’s Temple Sinai – a reformist synagogue - purchased a plot of land just north of the Hydro Transformer (see map above) and offered 130 sites for intermarried couples. It took several years for the cemetery to be authorized for this type of burial, but the first intermarriage burial was finally completed between Barbara Ann Dean and Denis Arthur Dean in 2013 and 2014 respectively. As of 2017, nine intermarried burials have been completed.

Today, about 3,850 people are buried in this quiet, picturesque, well-maintained Bais-Oilom. Each person is buried in a single grave, all of which are arranged in tight rows to maximize the space available. Atop many of the monuments are small stones left by friends and relatives who have visited. The stones are said to symbolize the permanence of memory. Faced with the fragility of life, a stone is a reminder that there is permanence amid the pain of death and while other things fade, stones and souls endure.

Researched and Written by Denise Harris

Today, about 3,850 people are buried in this quiet, picturesque, well-maintained Bais-Oilom. Each person is buried in a single grave, all of which are arranged in tight rows to maximize the space available. Atop many of the monuments are small stones left by friends and relatives who have visited. The stones are said to symbolize the permanence of memory. Faced with the fragility of life, a stone is a reminder that there is permanence amid the pain of death and while other things fade, stones and souls endure.

Researched and Written by Denise Harris