Northern Etobicoke Historical Self-Driving Tour - Part 1

HOW TO USE THIS DRIVING TOUR

- After each stop, you will find the driving instructions to the next stop. Read the driving instructions for the next stop completely before you head out as sometimes they will provide you with information about sites to look at en route.

- Don’t forget to use the separate map of the tour route that has been provided above and available HERE on Google Maps.

- Remember that many of the sites along the way are on private property. Please respect the owners by not trespassing.

Tour Overview

This is the first of two driving tours of that part of the former City of Etobicoke that lies north of Highway 401, approximately 40% of Etobicoke’s total area. The entire area was surveyed by William Hambly in 1798, dividing it into 100 acre (40 hectare) lots that were .25 miles (.4 Km) wide and ran between north/south concession roads that were .625 miles (1 Km) apart. The first land grants were made in the very early 1800s. Initially, settlers spent most of their time clearing the land so crops could be planted and erecting at least rudimentary houses and barns, often made of logs. By the 1840s, 84% of the land in Etobicoke was owned and 50% of the owned land was under cultivation. However, by 1878, 98.8% of the land was owned and 90% of the owned land was under cultivation. By the mid to late 1800s, most log buildings would have been replaced by frame, stone or brick structures.

Northern Etobicoke had excellent soil for agriculture, and was soon specializing in wheat, dairy, livestock and fruit farming. Because the area was used almost exclusively for farming, the population was sparser than southern Etobicoke, and there were only four communities large enough to have a post office: Highfield, Smithfield, Claireville and Thistletown.

A map of Etobicoke made in the early 1940s shows that northern Etobicoke was still primarily farmland with the same four villages. But World War II changed all that, and northern Etobicoke quickly became a suburban centre that provided jobs and homes for a burgeoning post-war population.

This tour highlights the pioneer history of this area and you will see all of the sites that have survived from the 19th century. It will also cover some aspects of modern history, focusing on the time period after World War II when the area saw unprecedented growth. In addition to having large residential areas and parks, northern Etobicoke has a significant number of industrial and commercial properties, and although all but one of the farms have disappeared, a few parcels of land still remain undeveloped.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS will be found in italics and located after each stop. Read the driving instructions for the next stop completely before you head out as sometimes they will provide you with information about sites to look at enroute. Tour I STARTS on the south side of Allenby Avenue, just east of Burrard Road. STOP near numbers 37 and 39 Allenby Avenue.

Northern Etobicoke had excellent soil for agriculture, and was soon specializing in wheat, dairy, livestock and fruit farming. Because the area was used almost exclusively for farming, the population was sparser than southern Etobicoke, and there were only four communities large enough to have a post office: Highfield, Smithfield, Claireville and Thistletown.

A map of Etobicoke made in the early 1940s shows that northern Etobicoke was still primarily farmland with the same four villages. But World War II changed all that, and northern Etobicoke quickly became a suburban centre that provided jobs and homes for a burgeoning post-war population.

This tour highlights the pioneer history of this area and you will see all of the sites that have survived from the 19th century. It will also cover some aspects of modern history, focusing on the time period after World War II when the area saw unprecedented growth. In addition to having large residential areas and parks, northern Etobicoke has a significant number of industrial and commercial properties, and although all but one of the farms have disappeared, a few parcels of land still remain undeveloped.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS will be found in italics and located after each stop. Read the driving instructions for the next stop completely before you head out as sometimes they will provide you with information about sites to look at enroute. Tour I STARTS on the south side of Allenby Avenue, just east of Burrard Road. STOP near numbers 37 and 39 Allenby Avenue.

Starting Point (Map A): Old Rexdale

Although many people refer to the entire area north of Highway 401 in general as “Rexdale”, the group of streets east of Islington Avenue, between Allenby Avenue and Hadrian Drive, was the original Rexdale subdivision, now often referred to as “Old Rexdale”. The area’s developer, Rex Wesley Heslop, has been called by some “The Father of Rexdale” and “Etobicoke’s Horatio Alger” – a man who started with nothing and ended up developing a large portion of Etobicoke.

Heslop was born on a farm just north of your present location where is father farmed and worked in construction. Heslop worked in construction himself for awhile, and then moved to Michigan where he became a successful car salesman. He moved to northern Ontario to mine, but after an accident in 1947, he returned to Etobicoke at the age of 50 and established Rex Heslop Homes Limited. F

First he built 400 homes on cheap land that the city had acquired for non-payment of taxes in the Alderwood area, between Brown’s Line and the Etobicoke Creek, south of Evans Avenue to Horner Avenue. The homes were built using free plans from the National Housing Authority, and there are streets in that area today named Heslop and Delma (after his wife.)

Heslop was born on a farm just north of your present location where is father farmed and worked in construction. Heslop worked in construction himself for awhile, and then moved to Michigan where he became a successful car salesman. He moved to northern Ontario to mine, but after an accident in 1947, he returned to Etobicoke at the age of 50 and established Rex Heslop Homes Limited. F

First he built 400 homes on cheap land that the city had acquired for non-payment of taxes in the Alderwood area, between Brown’s Line and the Etobicoke Creek, south of Evans Avenue to Horner Avenue. The homes were built using free plans from the National Housing Authority, and there are streets in that area today named Heslop and Delma (after his wife.)

Once the cheap lots in Alderwood were gone, Heslop turned his attention to farmland north of the planned western extension of the Toronto bypass, Highway 401. Malton’s aircraft industry was expanding and he felt that housing would soon be needed by their workers. The Etobicoke Township Council told Heslop they couldn’t pay for needed services, like water, sewers and schools, without new industry in the area, and they made an agreement with him that he could continue building houses if he also established new industry in the area at a ratio of 35% industrial assessment to 65% residential.

In 1951, Heslop bought the Wilbert Wardlaw farm on east side of Islington Avenue to build houses. At the same time, General Electric (GE) bought the Peter Wardlaw farm on west side of Islington Avenue and made plans to build a factory employing 1200. Soon after GE decided not to build and sold the property to Simpsons Sears; Sears is still on that site. With Heslop’s help, seven other industries soon bought building sites in Rexdale west of Kipling Avenue. One of the first was Angelstone Limited, which built a plant, yard & sales office on Taber Road. As you continue your tour through northern Etobicoke, you will notice the significant use of this new decorative building product that simulates stone. Within a few years, the Rexdale industrial area had grown to 122 hectares – the largest in the township.

Reeve Bev Lewis described the deal they had made with Heslop as “the salvation of Etobicoke” because it contributed so significantly to their industrial tax base.

On April 24, 1952, 40 employees of the AV Roe Aircraft Company in Malton met with Heslop and worked out an agreement to buy 40 homes on Allenby Avenue, the first homes sold in Rexdale. They were all bungalows or storey-and-a-half homes such as those you see at 36, 37, 38 and 39 Allenby Avenue. Many are brick, but some are faced in a distinctive concrete siding that he had earlier used in Alderwood, invented by Hans Sachau, a boat builder in Humber Bay.

Rexdale residents’ mail was originally addressed c/o Rex Heslop, RR 3, Weston, until a “Rexdale” post office opened in December, 1952 in the old Wilbert Wardlaw farmhouse, which then sat at the northwest corner of Allenby Avenue and Burrard Road. A new Rexdale post office was opened in 1955 in a small frame building on the east side of Kipling Avenue, north of Rexdale Boulevard.

Reeve Bev Lewis described the deal they had made with Heslop as “the salvation of Etobicoke” because it contributed so significantly to their industrial tax base.

On April 24, 1952, 40 employees of the AV Roe Aircraft Company in Malton met with Heslop and worked out an agreement to buy 40 homes on Allenby Avenue, the first homes sold in Rexdale. They were all bungalows or storey-and-a-half homes such as those you see at 36, 37, 38 and 39 Allenby Avenue. Many are brick, but some are faced in a distinctive concrete siding that he had earlier used in Alderwood, invented by Hans Sachau, a boat builder in Humber Bay.

Rexdale residents’ mail was originally addressed c/o Rex Heslop, RR 3, Weston, until a “Rexdale” post office opened in December, 1952 in the old Wilbert Wardlaw farmhouse, which then sat at the northwest corner of Allenby Avenue and Burrard Road. A new Rexdale post office was opened in 1955 in a small frame building on the east side of Kipling Avenue, north of Rexdale Boulevard.

Initially children were bussed to Humber Heights Public School on Lawrence Avenue West, but Elmlea Junior School soon opened on Hadrian Drive in May, 1953. Rexdale Plaza was built in 1956 on the east side of Islington Avenue, north of Allenby Avenue, once a major shopping centre in the area but now replaced with “big box” style stores.

Heslop also built most of the area often referred to as “New Rexdale”, west of Islington Avenue, north of Rexdale Boulevard, and the “Sunnydale” subdivision that you will see later in the tour.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Drive east on Allenby Avenue and turn right on Grierson Road. Turn left into the Pine Point Park parking lot and STOP at east end of the lot near 15 Grierson Road, the Tudor-style building overlooking the Humber River Valley.

Heslop also built most of the area often referred to as “New Rexdale”, west of Islington Avenue, north of Rexdale Boulevard, and the “Sunnydale” subdivision that you will see later in the tour.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Drive east on Allenby Avenue and turn right on Grierson Road. Turn left into the Pine Point Park parking lot and STOP at east end of the lot near 15 Grierson Road, the Tudor-style building overlooking the Humber River Valley.

Stop Two (Map B): Pine Point Park, 15 Grierson Road

Prior to the Rexdale subdivision being built, Pine Point Golf Course was located here in the Humber Valley and this Tudor-style building was its clubhouse.

Golf in this area started in 1925 when Cecil White paid $46,500 for a piece of land in the Humber Valley, south of today’s 401, which had been owned earlier by the Weston Golf Club. White already owned three other golf courses in the north and east suburbs of Toronto, and he chose this site to open his new Riverside Golf Course, with memberships advertised at $5.00 per year. White expanded the golf course in 1928 with a purchase of 97 hectares of land north of today’s 401 where Pine Point Park is located today. An old barn on the hillside here became their clubhouse.

Golf in this area started in 1925 when Cecil White paid $46,500 for a piece of land in the Humber Valley, south of today’s 401, which had been owned earlier by the Weston Golf Club. White already owned three other golf courses in the north and east suburbs of Toronto, and he chose this site to open his new Riverside Golf Course, with memberships advertised at $5.00 per year. White expanded the golf course in 1928 with a purchase of 97 hectares of land north of today’s 401 where Pine Point Park is located today. An old barn on the hillside here became their clubhouse.

By 1932, the golf course was sold for $62,500 to Frank Deakin, who ran it with his brother Bert. They changed the name to Pine Point Golf Course and annual dues became $25.00. They immediately replaced the old barn clubhouse with the one you see today. It was designed in a Tudor revival style overlooking the valley, with a lower level made of Humber river stone. Note the wrought iron “PP” for Pine Point adorning the stone chimney at the front of the building.

The clubhouse had a devastating fire in 1936, but was rebuilt in 1937, adding a kitchen and a one bedroom apartment for the groundskeeper at the south end. However, in 1947, the golf course was expropriated by the Ontario Highways Department for the planned Highway 401, which was completed through this area in 1954. The Highways Department sold 13 hectares of the property to the Township of Etobicoke in 1957. They reopened the former golf course as Rexdale’s first park, Pine Point. The former clubhouse became a community centre, with adjacent tennis courts and skating rink. Owned today by the City, this centre includes a rental banquet hall and has been the clubhouse of the Thistletown Lions’ Club since 1996.

Immediately north of Pine Point Golf Course was The Elms Golf Course, which was sold and the land developed in the mid-1960s as “The Elms” subdivision. The Elms Golf Course is remembered today in the names The Elms Park, The Elms Junior-Middle School, Elmhurst Drive and Golfdown Drive.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Allenby Avenue and turn right. Drive to the east end of Allenby and turn left on Hadrian Drive. Note Elmlea Junior School at 50 Hadrian Drive on your right as you pass; the school’s original 1950s section is still visible in the middle of today’s structure. Continue on Hadrian Drive to the stop sign at Burrard Road. In front of you, on the west side of Burrard Road, is the former site of Rexdale Plaza, built in 1956 as the 4th shopping centre in Toronto and now replaced by “big box” style stores. Turn right on Burrard Road, left on Bergamot Avenue, and then right on Islington Avenue. Drive north on Islington Avenue and turn left at Elmhurst Drive. Turn right at the first street, Pakenham Drive, and STOP as soon as possible on right side of the road. Walk back to the house at 105 Elmhurst Drive, on the south side of the road opposite your location. (Note: It is not safe to park on Elmhurst Drive.)

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Allenby Avenue and turn right. Drive to the east end of Allenby and turn left on Hadrian Drive. Note Elmlea Junior School at 50 Hadrian Drive on your right as you pass; the school’s original 1950s section is still visible in the middle of today’s structure. Continue on Hadrian Drive to the stop sign at Burrard Road. In front of you, on the west side of Burrard Road, is the former site of Rexdale Plaza, built in 1956 as the 4th shopping centre in Toronto and now replaced by “big box” style stores. Turn right on Burrard Road, left on Bergamot Avenue, and then right on Islington Avenue. Drive north on Islington Avenue and turn left at Elmhurst Drive. Turn right at the first street, Pakenham Drive, and STOP as soon as possible on right side of the road. Walk back to the house at 105 Elmhurst Drive, on the south side of the road opposite your location. (Note: It is not safe to park on Elmhurst Drive.)

Stop Three (Map C): Garbutt/Gardhouse Residence, 105 Elmhurst Drive

In the 1830s, George Garbutt purchased a 61 hectare lot here. A small creek runs through the property behind the house, a valuable asset to a pioneer farm. The original house is the small section at the back of the building, closer to the rear of the lot. Property assessment records indicate it was built c. 1860. It is a typical pioneer one-and-a-half storey home with a low gable roof, and walls of red brick with decorative yellow brick cornice under the eaves and quoins down each corner. There is an open verandah with a shed roof at the rear, and the original front door is flanked by flat-headed windows. There are also diminutive flat-headed windows in the top half storey, just under the roofline. After George Garbutt died late in the 19th century, his son William inherited the property.

The Gardhouse family started acquiring property in Etobicoke in 1826 and built a large, prosperous stock-breeding farm called Rosedale at Rexdale Boulevard and Highway 27. About 1903, William (Bill) Gardhouse, great grandson of the original Gardhouse settler, married

William Garbutt’s daughter Alice, who had inherited this property at 105 Elmhurst Drive. In 1915, they built an addition on the front of the original house in the Edwardian Classical style popular at that time. It is a 4-square plan of red brick with a hipped roof and a dormer in the roof at the front. The home’s new front door is in the east facade, sheltered by an open porch with a hipped roof. To the left of the entry is an arched, tri-sectioned window.

Bill Gardhouse had graduated from Guelph Agricultural College and, in addition to farming, was very active in politics: Deputy Reeve 1918-20 & 1927; Reeve 1921-24 & 1932-33; Warden of York County 1924; MPP for the West York riding 1935-41; and Roads Commissioner 1942-50. He died in 1950 at the age of 70. His son, Arnold, inherited the property and, in 1952, Arnold moved to a farm in Markham after selling this property to developers.

The Garbutt-Gardhouse residence is protected by a designation under the Ontario Heritage Act.

The Gardhouse family started acquiring property in Etobicoke in 1826 and built a large, prosperous stock-breeding farm called Rosedale at Rexdale Boulevard and Highway 27. About 1903, William (Bill) Gardhouse, great grandson of the original Gardhouse settler, married

William Garbutt’s daughter Alice, who had inherited this property at 105 Elmhurst Drive. In 1915, they built an addition on the front of the original house in the Edwardian Classical style popular at that time. It is a 4-square plan of red brick with a hipped roof and a dormer in the roof at the front. The home’s new front door is in the east facade, sheltered by an open porch with a hipped roof. To the left of the entry is an arched, tri-sectioned window.

Bill Gardhouse had graduated from Guelph Agricultural College and, in addition to farming, was very active in politics: Deputy Reeve 1918-20 & 1927; Reeve 1921-24 & 1932-33; Warden of York County 1924; MPP for the West York riding 1935-41; and Roads Commissioner 1942-50. He died in 1950 at the age of 70. His son, Arnold, inherited the property and, in 1952, Arnold moved to a farm in Markham after selling this property to developers.

The Garbutt-Gardhouse residence is protected by a designation under the Ontario Heritage Act.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue north on Pakenham Drive until it ends at Fordwich Crescent. Turn left & STOP in front of number 66 Fordwich Crescent

Stop Four (Map D): Kipling Heights Subdivision

The Kipling Heights subdivision lies between Islington and Kipling Avenues, running north from the Garbutt/Gardhouse property to the West Humber River valley. Monarch Construction and Realty Limited bought two farms here, totalling 185 hectares, from Percy and Andrew Barker for $1.8 million. Between 1956 and 1958, Monarch Construction, with the help of eight partner construction companies, built new houses over the entire area.

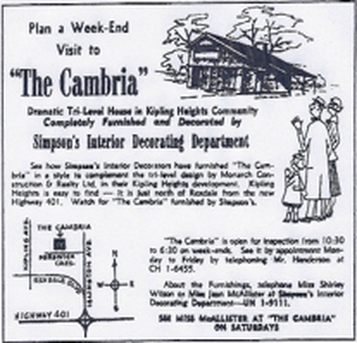

The architectural style in Kipling Heights is now called “Contempo” or “Mid-century Modern”, because it was so common in 1950s and 1960s subdivisions across North America. With a postwar upsurge in the economy, families were quick to embrace an architecture suited to all of the modern conveniences now available, such as refrigerators, electric stoves and continuous counter tops. Building products that had been restricted during the war were now available: steel, aluminum, a variety of surface finishes, and large sheets of glass for “picture windows”. Fireplaces were common with centred chimneys at the front or rear. Rooflines often had an off-centre peak, with a slope that extended further on one side to incorporate a carport, perfect for the family on the go. An inverted wing or “butterfly” roof with an off-centre “V” was often seen as well. Number 66 Fordwich Crescent was a Kipling Heights model home called “The Cambria”, advertised as a “dramatic tri-level house” and furnished by Simpson’s Interior Decorating Department.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue west on Fordwich Crescent and follow it as it turns north. At Hinton Road turn left and drive west. Turn left at the first street on the left, Arbordell Road, into West Acres Seniors Apartments. STOP in any parking spot you can find on the right or left as soon as possible after you enter the complex

Stop Five (Map E): West Acres Seniors Apartments, Arbodell Road

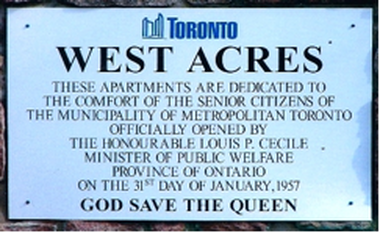

In 1954, Metropolitan Toronto Housing Corporation was established to build low-rent housing for seniors and others in need. In 1957, West Acres was opened as the first development built specifically for seniors by Metropolitan Toronto. The development consists of 12 two-storey buildings with apartments along each side, back to back, and each with its own exterior door and small verandah or balcony. Note the introductory sign on left as you entered the complex, which concludes with the phrase “God Save the Queen”. The original sign was replaced after the Toronto amalgamation in 1999, but the text is the same and its final sentiment truly seems to be from another era. West Acres Seniors’ Community Centre is immediately to the west of the houses on the same property.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Hinton Road and turn left. Stop on the north side of the road close to Kipling Avenue where you can see the large red and slate coloured building on the south side of Hinton Road

Stop Six (Map F): Kipling Acres Long Term Care Facility, 2233 Kipling Avenue

Kipling Acres Long Term Care Facility was built in 1959 on a 20 acre property. Many of its residents are seniors, but a number are younger adults. It offers long term care (e.g. for Alzheimer’s patients) or short term care (e.g. for people undergoing rehabilitation after surgery.) It also offers Adult Day Programs and short-term Respite Care for an individual whose caregiver will be away.

It is currently undergoing a major redevelopment. Phase 1 is completed and this new building now houses 192 residents. Phase 2 will be completed by 2016, making space for another 145 residents for a total of 337.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue west along Hinton Road and turn left. Turn right on Kipling Avenue. Drive north and turn left at the next lights, Westhumber Boulevard. Drive west to the fourth street, Amoro Drive, and turn left. STOP on the right beside Sunnydale Park, in the second block south of Westhumber Boulevard.

It is currently undergoing a major redevelopment. Phase 1 is completed and this new building now houses 192 residents. Phase 2 will be completed by 2016, making space for another 145 residents for a total of 337.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue west along Hinton Road and turn left. Turn right on Kipling Avenue. Drive north and turn left at the next lights, Westhumber Boulevard. Drive west to the fourth street, Amoro Drive, and turn left. STOP on the right beside Sunnydale Park, in the second block south of Westhumber Boulevard.

Stop Seven (Map G): Sunnydale Subdivision

You are now in Rex Heslop’s “Sunnydale” subdivision, built in the late 1950s. All of the houses here are made of brick: none have the concrete fronts you saw in Old Rexdale. Note the generous use of “Angelstone” on most of the houses, a characteristic of many Toronto homes built in the 1950s and 1960s. Once considered the latest in decorative technology and advertised as having “the permanent graciousness of rock ashlar”, this simulated stone product has since fallen into disfavour, perhaps because it was frequently used to update older buildings, often unsuccessfully from an aesthetic point-of-view.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: As you drive along the next few streets, look at Heslop’s Sunnydale homes. Note the use of Angelstone, sometimes covering the entire front of a house. Continue south on Amoro Drive. Turn right at Porterfield Road and then right at Delsing Drive. Turn left at Westhumber Boulevard and turn right at the second street, Moon Valley Drive. Follow Moon Valley Drive as it circles back to Westhumber Boulevard and turn left. Drive east and turn left into the parking lot of Esther Lorrie Park and STOP. Get out of car to enjoy the expansive view of the West Humber River valley.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: As you drive along the next few streets, look at Heslop’s Sunnydale homes. Note the use of Angelstone, sometimes covering the entire front of a house. Continue south on Amoro Drive. Turn right at Porterfield Road and then right at Delsing Drive. Turn left at Westhumber Boulevard and turn right at the second street, Moon Valley Drive. Follow Moon Valley Drive as it circles back to Westhumber Boulevard and turn left. Drive east and turn left into the parking lot of Esther Lorrie Park and STOP. Get out of car to enjoy the expansive view of the West Humber River valley.

Stop Eight (Map H): Esther Lorrie Park

This view from Esther Lorrie Park provides one of the most spectacular views of the wide valley of the west branch of the Humber River, which dominates the topography in a wide swath across Etobicoke from east to west, north of Rexdale Boulevard.

The houses you just passed on Westhumber Boulevard and Moon Valley Drive were built by Millmink Developments. They are larger homes, many of which are on premium lots overlooking this valley. As in most subdivisions, many of the streets were named by the developer. Moon Valley Drive was named by Millmink’s owner, who was struck by the beauty of a full moon he saw over the Humber Valley one clear night.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Turn left onto Westhumber Boulevard. Turn left at the second street, Jansusie Road, and STOP in front of any one of the four low apartment buildings on the right side of the street.

The houses you just passed on Westhumber Boulevard and Moon Valley Drive were built by Millmink Developments. They are larger homes, many of which are on premium lots overlooking this valley. As in most subdivisions, many of the streets were named by the developer. Moon Valley Drive was named by Millmink’s owner, who was struck by the beauty of a full moon he saw over the Humber Valley one clear night.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Turn left onto Westhumber Boulevard. Turn left at the second street, Jansusie Road, and STOP in front of any one of the four low apartment buildings on the right side of the street.

Stop Nine (Map I): Jansusie Apartments

These four low “garden” apartments on the east side of Jansusie Road were built in the summer of 1958 and were named after the developer’s four children: Jeffrey Gardens (No. 5), Shelley Gardens (No. 15), Pamela Gardens (No. 25), and Stephen Gardens (No. 35). Each building’s name originally appeared in gold on the glass of its front door.

These were considered rather charming buildings at the time they were built, each with a front sidewalk that split and curved around trees, gardens and a water fountain. Each building’s lobby was decorated in terrazzo using different colours and patterns that included that building’s initials: SG can still be seen in the lobby of No. 15 and PG in No. 25. The buildings had typical 1950s carports at the rear, which were torn down in the 1970s.

Jansusie Road was named for two of the developer’s family members, as was Millmink Street that runs west off Jansusie.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Drive north on Jansusie Road and stop in front of the apartment buildings immediately ahead of you at 60 and 70 Esther Lorrie Drive.

These were considered rather charming buildings at the time they were built, each with a front sidewalk that split and curved around trees, gardens and a water fountain. Each building’s lobby was decorated in terrazzo using different colours and patterns that included that building’s initials: SG can still be seen in the lobby of No. 15 and PG in No. 25. The buildings had typical 1950s carports at the rear, which were torn down in the 1970s.

Jansusie Road was named for two of the developer’s family members, as was Millmink Street that runs west off Jansusie.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Drive north on Jansusie Road and stop in front of the apartment buildings immediately ahead of you at 60 and 70 Esther Lorrie Drive.

Stop Ten (Map J): 60 and 70 Esther Lorrie Drive

In the summer of 1956, one of the area’s developers held a family picnic on grass overlooking a valley. A man who attended this picnic at age seven remembers that as far as he could see, there was nothing but trees, grass and a few cows. He was told that within a few years, the whole area would be covered with houses and apartment buildings. This picnic was held where the backyard of 70 Esther Lorrie Drive is today, overlooking the West Humber River valley. And indeed, within a few years of that picnic, the whole area had been developed.

60 and 70 Esther Lorrie Drive were built c. 1960 and, at seven storeys, were the tallest apartment buildings in Etobicoke at the time.

Seven stories was the height limit of an Etobicoke fire truck ladder. The houses on Esther Lorrie Drive south of the apartment buildings were also built c. 1960, overlooking the West Humber River valley. One of the model homes was listed at $29,500, a higher than average price for a northern Etobicoke suburb at that time. Esther Lorrie Drive was named after two of the developer’s family members.

60 and 70 Esther Lorrie Drive were built c. 1960 and, at seven storeys, were the tallest apartment buildings in Etobicoke at the time.

Seven stories was the height limit of an Etobicoke fire truck ladder. The houses on Esther Lorrie Drive south of the apartment buildings were also built c. 1960, overlooking the West Humber River valley. One of the model homes was listed at $29,500, a higher than average price for a northern Etobicoke suburb at that time. Esther Lorrie Drive was named after two of the developer’s family members.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Turn around, return to Kipling Avenue and turn left. Drive north and turn left at the first street, John Garland Boulevard. Turn right at the second street, Kendleton Drive, and then right at the first street, Warrendale Court. STOP in front of numbers 2, 3 and 4 Warrendale Court.

NOTE: In Google Maps, this stop represents the end of the driving instructions in Part A of this tour. Instructions for Part B begin now, and map lettering re-starts from B in the new section of this tour, starting below.

Stop Eleven (Map B): Warrendale

Most of the buildings on this street were at the very frontier of the now-common practice of treating severely emotionally-disturbed children in a family-like setting where they are free to express their feelings. In the 1960s, many professionals in psychiatry were starting to believe that such an environment helped heal disturbed children who had never experienced safety, structure and close relationships at home. Even though the “family” situation may seem artificial to an observer, the feelings of being safe and loved were real to the child and opened them to positive behaviour change.

This treatment centre was called Warrendale. John Brown was the centre’s director, a social worker who had developed special techniques for working with deeply troubled children during 12 years at a centre called St. Faith’s Lodge, founded in 1923 in Newmarket. In 1952, this centre was reborn as “Warrendale”, named after the late Mrs. Warren who had been President of its Board for 30 years.

This treatment centre was called Warrendale. John Brown was the centre’s director, a social worker who had developed special techniques for working with deeply troubled children during 12 years at a centre called St. Faith’s Lodge, founded in 1923 in Newmarket. In 1952, this centre was reborn as “Warrendale”, named after the late Mrs. Warren who had been President of its Board for 30 years.

John Brown’s basic technique for handling a child having an emotional tantrum was “holding”: one (or more) attendants sat with the child in front of them on the floor, pinned the child’s arms and legs firmly but peaceably, and then let the child “rip”. Complete freedom of feeling was the essence, with human restraint to keep the child from hurting themselves or others, and the physical presence of a caring “somebody else” with whom they had formed an attachment so the child knows he or she has not been abandoned.

Four buildings opened on the north side of Warrendale Court in December 1965, and each was a group “home” for 10-12 children. Groups were formed on the basis of family-like groupings, with a mix of sexes and ages. Each house had four therapeutic group leaders and one overnight staff person, all of whom committed to work there for a minimum of two years. Two more homes opened by mid-1966, as well as a school and an administration building.

Four buildings opened on the north side of Warrendale Court in December 1965, and each was a group “home” for 10-12 children. Groups were formed on the basis of family-like groupings, with a mix of sexes and ages. Each house had four therapeutic group leaders and one overnight staff person, all of whom committed to work there for a minimum of two years. Two more homes opened by mid-1966, as well as a school and an administration building.

In the spring of 1966, the CBC commissioned a now-legendary documentary called Warrendale. It was directed by Canadian Allan King in a cinema verité style. King and his camera crew spent a month just getting acquainted with the children, and then five more weeks filming the children’s normal everyday activities. 40,000 feet of film were edited into a 100-minute documentary. When the CBC saw it, they were so shocked by the children’s swearing that they refused to air it, and it was not seen on television for 30 years. However, it was shown in Toronto theatres and shared the grand prize at the Canadian Film Festival in Montreal. In addition, it was released to huge international acclaim, winning foreign film awards in Cannes, New York and Britain.

This film, with its raw honesty, caused great controversy within the psychiatric community, among Warrendale board members, and within the public at large. Warrendale’s Board of Directors disliked this negative attention and discord developed between them and John Brown on how the centre should be run. In June 1966, Brown was fired. Warrendale’s staff, who were very supportive of Brown, agreed to continue working while the situation was sorted out. However, on September 7, 1966, the Board unexpectedly sold Warrendale to the Ontario Government for $1. That same day the staff walked out in support of Brown’s philosophies, hoping this would somehow force the children back into his care. The government turned Warrendale over to nearby Thistletown Regional Centre, another facility for disturbed children, and their staff had to deal with the bereft children with no advance preparation.

John Brown went on to establish his own private, non-profit, charitable organization of children’s camps, schools and residential homes across Canada, the United States and Europe called “Browndale”, where he was free to further develop and implement his programs for helping these deeply ill children.

As the staff had hoped, one year after this Warrendale location was closed, 52 of the 57 children who had been in residence here had found their way back to a John Brown-run facility. Many of Brown’s views and techniques have been incorporated into modern psychiatric programs for children and youths. Allan King passed away in 2009 at the age of 79, but his moving and ground-breaking documentary lives as a staple in both film schools and psychiatry training.

All of the buildings surrounding Warrendale Court were part of the Warrendale facility and are legally still one continuous property. Three of the original four Warrendale group homes remain at numbers 2, 3 and 4 Warrendale Court; the 4th home at number 1 has been replaced by a new building. The semi-detached unit at number 11 housed the 5th and 6th group homes that opened in 1966. Number 15 was possibly the Warrendale school, and number 6 is a newer building that likely replaced the original administration building. These seven building are owned by the City and still house organizations assisting youths in need, e.g. Youth without Shelter provides housing for homeless youths trying to complete high school and CASATTA assists young offenders to find jobs.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Kendleton Drive and turn left. Turn right at John Garland Boulevard. Turn right at the driveway into the parking lot of Greenholme Junior Middle School and STOP.

John Brown went on to establish his own private, non-profit, charitable organization of children’s camps, schools and residential homes across Canada, the United States and Europe called “Browndale”, where he was free to further develop and implement his programs for helping these deeply ill children.

As the staff had hoped, one year after this Warrendale location was closed, 52 of the 57 children who had been in residence here had found their way back to a John Brown-run facility. Many of Brown’s views and techniques have been incorporated into modern psychiatric programs for children and youths. Allan King passed away in 2009 at the age of 79, but his moving and ground-breaking documentary lives as a staple in both film schools and psychiatry training.

All of the buildings surrounding Warrendale Court were part of the Warrendale facility and are legally still one continuous property. Three of the original four Warrendale group homes remain at numbers 2, 3 and 4 Warrendale Court; the 4th home at number 1 has been replaced by a new building. The semi-detached unit at number 11 housed the 5th and 6th group homes that opened in 1966. Number 15 was possibly the Warrendale school, and number 6 is a newer building that likely replaced the original administration building. These seven building are owned by the City and still house organizations assisting youths in need, e.g. Youth without Shelter provides housing for homeless youths trying to complete high school and CASATTA assists young offenders to find jobs.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to Kendleton Drive and turn left. Turn right at John Garland Boulevard. Turn right at the driveway into the parking lot of Greenholme Junior Middle School and STOP.

Stop Twelve (Map C): Public Housing In Northern Etobicoke

When Metropolitan Toronto was formed in 1953, one of the reasons for its formation was the shortage of space in downtown Toronto for affordable housing for low income earners and the elderly. However, North York, Scarborough and Etobicoke had lots of vacant farmland, and it was much cheaper than land in the city core. In 1955, the Metropolitan Toronto Housing Authority was formed to administer low rental housing projects, in partnership with the federal and provincial governments.

In 1961, their first small project, Scarlettwood, was completed on the east side of Scarlett Road, halfway between Lawrence and Eglinton. Their next undertaking, referred to as the “Thistletown Project”, was much larger and more hotly debated. The proposal was to build public housing on over 200 hectares that the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) had acquired in 1952, between Kipling Avenue and Martin Grove Road, from the West Humber River north to beyond Albion Road. The plan for this new subdivision was registered in 1964 and, in 1965, Greenholme Junior Middle School was planned. The school was named for the Rowntree family’s Greenholme Mills that operated on the Humber River northwest of here from 1848 to the early 20th century.

At this time, Etobicoke had a stated policy of only approving “above average” communities in terms of the quality of the housing built. Single family homes were encouraged, while most rental housing was considered unfavourably. Despite Etobicoke Council’s strong objections, low rent public housing was built on John Garland Boulevard and Jamestown Crescent by 1967. A 1972 Ontario Housing Corporation (OHC) report confirmed that Etobicoke’s council was against the building of any more OHC residential units north of Highway 401. Perhaps as an indicator of the power wielded by Metropolitan Toronto, northern Etobicoke ended up with one of the highest concentrations of low rent housing in Metro.

Jamestown Crescent, a public townhouse development on a crescent immediately west of this school parking lot, has seen its share of gang violence and is known to local residents as “Doomstown”. In 2006, in a raid by 600 Toronto police officers, 125 gang members were arrested, the largest number of gang arrests made at one time in Toronto’s history. Most of those arrested were 17 to 25 years old and members of the “Jamestown Crew” gang.

Most of the area from John Garland Boulevard north to Steeles Avenue, and from Martin Grove Road east to the Humber River, has been designated the “Jamestown Priority Neighbourhood” by the City of Toronto. The community receives funding and services to help improve the area’s infrastructure and social services.

In 1961, their first small project, Scarlettwood, was completed on the east side of Scarlett Road, halfway between Lawrence and Eglinton. Their next undertaking, referred to as the “Thistletown Project”, was much larger and more hotly debated. The proposal was to build public housing on over 200 hectares that the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) had acquired in 1952, between Kipling Avenue and Martin Grove Road, from the West Humber River north to beyond Albion Road. The plan for this new subdivision was registered in 1964 and, in 1965, Greenholme Junior Middle School was planned. The school was named for the Rowntree family’s Greenholme Mills that operated on the Humber River northwest of here from 1848 to the early 20th century.

At this time, Etobicoke had a stated policy of only approving “above average” communities in terms of the quality of the housing built. Single family homes were encouraged, while most rental housing was considered unfavourably. Despite Etobicoke Council’s strong objections, low rent public housing was built on John Garland Boulevard and Jamestown Crescent by 1967. A 1972 Ontario Housing Corporation (OHC) report confirmed that Etobicoke’s council was against the building of any more OHC residential units north of Highway 401. Perhaps as an indicator of the power wielded by Metropolitan Toronto, northern Etobicoke ended up with one of the highest concentrations of low rent housing in Metro.

Jamestown Crescent, a public townhouse development on a crescent immediately west of this school parking lot, has seen its share of gang violence and is known to local residents as “Doomstown”. In 2006, in a raid by 600 Toronto police officers, 125 gang members were arrested, the largest number of gang arrests made at one time in Toronto’s history. Most of those arrested were 17 to 25 years old and members of the “Jamestown Crew” gang.

Most of the area from John Garland Boulevard north to Steeles Avenue, and from Martin Grove Road east to the Humber River, has been designated the “Jamestown Priority Neighbourhood” by the City of Toronto. The community receives funding and services to help improve the area’s infrastructure and social services.

DRIVING INSTRUCTION: Return to John Garland Boulevard and turn left. At Kipling Avenue, turn left and drive north to Albion Road. Turn right and drive southeast to Islington Avenue. STOP as close to the Albion/Islington intersection as possible.

Stop Thirteen (Map D): Thistletown

You are now at the original main intersection of what was once the village of Thistletown. Sadly, there isn’t much left of old Thistletown, but it does have five properties that are on the City of Toronto’s Heritage Register. In addition, two other heritage properties from Thistletown have been moved elsewhere and been preserved.

One of the moved houses is Llewellyn Hill Farm, built of Humber riverstone c. 1855 by original land grantee Aaron Barker. It was located on the west side of Islington Avenue, on a hill south of the West Humber River. In 1956, it was slated for demolition to build Thistletown Collegiate. Originally a two storey house, it was saved at the 11th hour when purchased by Elizabeth and Don Strathdee, who disassembled, moved, and carefully reconstructed it as a one-and –a-half storey house at 85 Yorkleigh Avenue (near Scarlett Road and Lawrence Avenue). (Note: This private house is not visible from the street.)

One of the moved houses is Llewellyn Hill Farm, built of Humber riverstone c. 1855 by original land grantee Aaron Barker. It was located on the west side of Islington Avenue, on a hill south of the West Humber River. In 1956, it was slated for demolition to build Thistletown Collegiate. Originally a two storey house, it was saved at the 11th hour when purchased by Elizabeth and Don Strathdee, who disassembled, moved, and carefully reconstructed it as a one-and –a-half storey house at 85 Yorkleigh Avenue (near Scarlett Road and Lawrence Avenue). (Note: This private house is not visible from the street.)

Thistletown was originally called Conat’s Corners after a local tavern keeper. John Grubb, accompanied by his wife Janet and their nine children, arrived from Scotland in 1833, and bought a 40 hectare lot on the Humber River. In addition to being a farmer, John Grubb was the first President of the Weston Road Plank Road Company that built a toll road from Dundas Street, through Weston, and then in 1841 extended it up Albion Road to Thistletown. In 1844, Islington Avenue was opened as far north as Conat’s Corners. North of Albion, the road was built by the Pine Grove Plank Road Company.

John Grubb hired surveyor John Stoughton Dennis to prepare a plan for a town to be called St. Andrews (named for Grubb’s birthplace in Scotland) on land he had bought on three of the corners at the Albion/Islington intersection. The plan was registered in 1847, the first to be filed in Etobicoke. A post office opened in 1851, and John Thistle was the first postmaster. By the mid-1860s the town was asked to select a different name because mail was frequently misdirected between the Etobicoke St. Andrews and St. Andrews, New Brunswick. A new name of Thistletown was selected to honour both their postmaster and his father, local doctor William Thistle, much to the disappointment of the Grubb family.

John Grubb hired surveyor John Stoughton Dennis to prepare a plan for a town to be called St. Andrews (named for Grubb’s birthplace in Scotland) on land he had bought on three of the corners at the Albion/Islington intersection. The plan was registered in 1847, the first to be filed in Etobicoke. A post office opened in 1851, and John Thistle was the first postmaster. By the mid-1860s the town was asked to select a different name because mail was frequently misdirected between the Etobicoke St. Andrews and St. Andrews, New Brunswick. A new name of Thistletown was selected to honour both their postmaster and his father, local doctor William Thistle, much to the disappointment of the Grubb family.

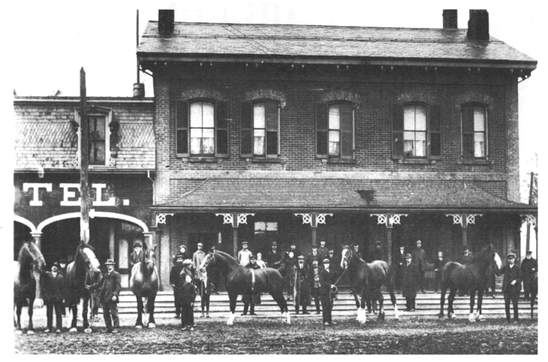

On the southwest corner of Albion & Islington was Mr. Tibb’s Tavern, built by Archibald Gallanough. It was the site of the poll where voters in Etobicoke’s Ward 5 elected their first township councillor in 1850. It later became Thomas Holmes’ Albion Hotel, a landmark in the village for many years.

Thistletown became a “police village” in 1933, and remained one until 1961. In Ontario, when a community was too small to become a “village”, the county could pass a by-law to create a “police village”. The word “police” refers to the new village’s ability to take action to maintain public order. A police village was governed by elected local trustees with powers to tax residents for local improvements, such as street lights, sidewalks, garbage collection and fire services.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Drive south on Islington Avenue and turn left at the first street, Barker Avenue. Turn right onto Riverdale Drive and STOP in front of the log house at 34 Riverdale Drive.

Thistletown became a “police village” in 1933, and remained one until 1961. In Ontario, when a community was too small to become a “village”, the county could pass a by-law to create a “police village”. The word “police” refers to the new village’s ability to take action to maintain public order. A police village was governed by elected local trustees with powers to tax residents for local improvements, such as street lights, sidewalks, garbage collection and fire services.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Drive south on Islington Avenue and turn left at the first street, Barker Avenue. Turn right onto Riverdale Drive and STOP in front of the log house at 34 Riverdale Drive.

Stop Fourteen (Map E): Franklin Carmichael Art Centre, 34 Riverdale Drive

In 1932 Dr. Agnes Ann Curtin, a teacher, artist and physician, built a log house at 34 Riverdale Drive on one hectare of land. She had graduated as a physician from the University of Toronto in 1920, and her medical practice was concerned with the physical & psychological health of women. She arranged for the Boy Scouts to plant 4000 trees in this area, mostly conifers, which still give the whole area a woodsy atmosphere.

One of Dr. Curtin’s patients was the widow of Group of Seven artist, Franklin Carmichael. In 1952, after Dr. Curtin retired, she formed an art group in her home and asked Mrs. Carmichael’s permission to name the group after her husband. Mrs. Carmichael not only consented, but attended the group’s exhibitions and donated some of her late husband’s works as prizes.

In 1971, Dr. Curtin deeded her home to the Borough of Etobicoke with the proviso that it continue as an art centre after her death. When Dr. Curtin died in 1977, her ashes were buried beneath a stone, with a plaque donated by the Borough of Etobicoke, under her favourite walnut tree, just to the left of the entry walkway. Today, over 25 art classes are held in the centre each week and the house is listed on City of Toronto’s Inventory of Heritage Properties.

One of Dr. Curtin’s patients was the widow of Group of Seven artist, Franklin Carmichael. In 1952, after Dr. Curtin retired, she formed an art group in her home and asked Mrs. Carmichael’s permission to name the group after her husband. Mrs. Carmichael not only consented, but attended the group’s exhibitions and donated some of her late husband’s works as prizes.

In 1971, Dr. Curtin deeded her home to the Borough of Etobicoke with the proviso that it continue as an art centre after her death. When Dr. Curtin died in 1977, her ashes were buried beneath a stone, with a plaque donated by the Borough of Etobicoke, under her favourite walnut tree, just to the left of the entry walkway. Today, over 25 art classes are held in the centre each week and the house is listed on City of Toronto’s Inventory of Heritage Properties.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue south on Riverdale Drive and turn left at the south end onto Jason Road. STOP on the south side of Jason Road as close to the corner as possible. You may wish to leave your car and walk to more easily see all four houses at this stop

Stop Fifteen (Map F): Grubb Family Properties

When John and Janet Grubb and their family emigrated from Scotland in 1833, they bought a 40 hectare farm on the west side of Albion Road, overlooking the West Humber River, and called it “Elm Bank”. Initially they lived in the riverstone house on the south side of the street that is now 23 Jason Road, built by a previous owner between 1800 and 1820. It is the oldest building in Etobicoke, and one of the five oldest buildings in Toronto. The family called it “Lavinia Cottage”, after their youngest daughter, Lavinia, who was just three years old in 1833. C. 1834, Grubb built a new home, now 19 Jason Road, immediately behind or south of No. 23. The new house was also built of Humber riverstone, in a Regency cottage style, with a verandah facing south to the river. No. 23 became servants’ quarters, and the two houses were connected by above and below ground passageways.

John Grubb’s son, William changed the spelling of their surname to “Grubbe”. After William’s death in 1890, the family was forced to sell Elm Bank as a result of financial problems resulting from the poor fiscal performance of the Weston & Albion Plank Road Companies. However, in 1972, No. 23 was purchased back into the Grubb family by William’s granddaughter-in-law, Mabel Grubbe. The family also bought back No. 19. Soon after. Michael FitzGerald (Mabel’s grandson and John Grubb’s great-great-great grandson) moved into the house “temporarily” after graduating from university… and never left. He has since bought both houses, and in 2008 had them designated under the Ontario Heritage Act to prevent future owners from demolishing them.

Across the street, 32 Jason Road was built on the foundation of the Grubb’s 1835 barn. It’s not known when it was converted into a residence, but the second storey was added in 1918.

The lower level of 34 Jason Road, at the corner of Riverdale Drive, was built in 1835 to house the Grubbs’ pigs. During WWI, it was converted into a residence. Dr. E.F. Irwin added a wing in the 1920s.

Sometime between 1835 and 1850, John Grubb built second riverstone house called “Brae Burn” on the east side of Albion Road. After John Grubb‘s death in 1850, his son Andrew lived in Brae Burn with his sister Eliza and her husband, Herman Wittrock. The house was destroyed by fire in 1852, but rebuilt immediately. In 1963, the entire house, with its two-foot thick walls, was taken apart and reassembled at Black Creek Pioneer Village where it was used originally as the Village Superintendent’s home. By 2002, the house was vacant and boarded up when Black Creek Pioneer Village leased the home and eight acres of land around it to Toronto’s Parks and Forestry Department. Since 2007, the house and land have been used as part of Toronto’s Urban Farm Project, where two dozen urban youths in difficulty are trained in urban organic farming each summer. The house is used as an office and training space. While not open to the public, the house can still be seen on the east side of Jane Street, just south of Steeles Avenue West.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue east on Jason Road and turn left onto Sims Crescent, which becomes Gibson Avenue. Stop in front of No. 11. You will not be able to see this house well because it is set well back from the street and surrounded by foliage, but please do not trespass.

The lower level of 34 Jason Road, at the corner of Riverdale Drive, was built in 1835 to house the Grubbs’ pigs. During WWI, it was converted into a residence. Dr. E.F. Irwin added a wing in the 1920s.

Sometime between 1835 and 1850, John Grubb built second riverstone house called “Brae Burn” on the east side of Albion Road. After John Grubb‘s death in 1850, his son Andrew lived in Brae Burn with his sister Eliza and her husband, Herman Wittrock. The house was destroyed by fire in 1852, but rebuilt immediately. In 1963, the entire house, with its two-foot thick walls, was taken apart and reassembled at Black Creek Pioneer Village where it was used originally as the Village Superintendent’s home. By 2002, the house was vacant and boarded up when Black Creek Pioneer Village leased the home and eight acres of land around it to Toronto’s Parks and Forestry Department. Since 2007, the house and land have been used as part of Toronto’s Urban Farm Project, where two dozen urban youths in difficulty are trained in urban organic farming each summer. The house is used as an office and training space. While not open to the public, the house can still be seen on the east side of Jane Street, just south of Steeles Avenue West.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue east on Jason Road and turn left onto Sims Crescent, which becomes Gibson Avenue. Stop in front of No. 11. You will not be able to see this house well because it is set well back from the street and surrounded by foliage, but please do not trespass.

Stop Sixteen (Map G): Torhaven, 11 Gibson Avenue

This large house was built in 1916 by Reverend Robert A. Sims and his wife Beatrice. Reverend Sims had been educated at the University of Toronto and became an Anglican priest. His first position was as curate at an Anglican church in Chatham, where he met and married Beatrice Atkinson. In 1901, Robert became rector at the Anglican Church of the Messiah on Avenue Road in Toronto and they moved to 17 Admiral Road. After 1915, Robert semi-retired, although he was still officially the church’s rector until 1928.

In 1916, the Sims and their four children - Hamilton (15), Eileen (12), Philip (9) and Elisabeth (7) – moved into their new home, built on a 1.2 hectare lot, overlooking the beautiful Humber River valley. The home was constructed of Humber rivers tone and was surrounded on three sides with open verandahs. The house was originally one storey at the front, with a large lower level down the hill at the rear. The Sims called their new home “Norwood”.

Robert and Beatrice Sims sold Norwood in 1946 and returned to Toronto to live at 367 Blythwood Road. Robert died that same year at the age of 85. Beatrice died at the age of 84 in 1954.

Two of Robert’s sisters, Florence and Emma, never married and lived together in Toronto where they were both teachers. Emma died in the 1919 flu epidemic. Florence retired from teaching in 1917 and bought the lot immediately south of Norwood, living in a small cottage on the property that had been built by an earlier owner but was later demolished. Florence Sims died in 1937 at the age of 74.

All of the Sims children were university educated, married and had children. Hamilton became a scientist and worked at the University of Toronto, but caught tuberculosis in 1942, passing away of the disease in 1948. Eileen and her family resided in North Toronto and she lived to be 88 years of age. Philip and his family lived in Montreal.

In 1938, the Sims’ younger daughter, Elisabeth, married Dr. Albert Hoemberg, a German historian she had met when she was a University of Toronto “Davis Exchange Scholar” to Germany in 1934-5. The wedding took place in Canada, but they immediately moved to Germany, only to find themselves trapped by World War II and a Nazi regime that Albert and his family detested. Inevitably, in 1940 Albert was conscripted, but because he had weak lungs, he was assigned to the Luftwaffe ground staff and stationed for most of the war in Paris.

For six years, Elisabeth and Albert only saw each other during his occasional short leaves. For safekeeping, they buried their diaries and letters in the garden of their home near Műnster where Elisabeth spent the war with their three children. In 1950, Elisabeth assembled all of their letters and diaries, and they were published in a book called Thy People, My People. Very popular in a post-war world, this book offered rare insights, not only into life in Germany during the war, but also into the often-shocking means used by British officers to right the wrongs of the war during Allied occupation post-war. This book is still considered a valuable primary resource about World War II and is available in reference libraries across Canada. In the 1970s, after Albert died, Elisabeth returned to Canada to live with her elder son and spent the rest of her life in Nanaimo BC.

Two of Robert’s sisters, Florence and Emma, never married and lived together in Toronto where they were both teachers. Emma died in the 1919 flu epidemic. Florence retired from teaching in 1917 and bought the lot immediately south of Norwood, living in a small cottage on the property that had been built by an earlier owner but was later demolished. Florence Sims died in 1937 at the age of 74.

All of the Sims children were university educated, married and had children. Hamilton became a scientist and worked at the University of Toronto, but caught tuberculosis in 1942, passing away of the disease in 1948. Eileen and her family resided in North Toronto and she lived to be 88 years of age. Philip and his family lived in Montreal.

In 1938, the Sims’ younger daughter, Elisabeth, married Dr. Albert Hoemberg, a German historian she had met when she was a University of Toronto “Davis Exchange Scholar” to Germany in 1934-5. The wedding took place in Canada, but they immediately moved to Germany, only to find themselves trapped by World War II and a Nazi regime that Albert and his family detested. Inevitably, in 1940 Albert was conscripted, but because he had weak lungs, he was assigned to the Luftwaffe ground staff and stationed for most of the war in Paris.

For six years, Elisabeth and Albert only saw each other during his occasional short leaves. For safekeeping, they buried their diaries and letters in the garden of their home near Műnster where Elisabeth spent the war with their three children. In 1950, Elisabeth assembled all of their letters and diaries, and they were published in a book called Thy People, My People. Very popular in a post-war world, this book offered rare insights, not only into life in Germany during the war, but also into the often-shocking means used by British officers to right the wrongs of the war during Allied occupation post-war. This book is still considered a valuable primary resource about World War II and is available in reference libraries across Canada. In the 1970s, after Albert died, Elisabeth returned to Canada to live with her elder son and spent the rest of her life in Nanaimo BC.

Norwood has had four owners since the Sims, and either the second or third owner changed the name of the house to “Torhaven”, meaning “refuge on a rocky peak”. Over the years, many changes have been made to the home, including enclosing the porches, opening up the attic with dormers, and reconfiguring the interior. Members of the McIlraith family have owned the home since 1965, including Dr. John McIlraith who was a Thistletown physician.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue north on Gibson Avenue. Turn left on Barker Avenue. Turn right on Riverdale Drive. Turn left on College Street. Turn right into the parking lot beside the Thistletown Multi-Service Centre at 925 Albion Road. STOP car and walk along laneway on the south side of the Thistletown Multi-Service Centre into the park at the rear.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Continue north on Gibson Avenue. Turn left on Barker Avenue. Turn right on Riverdale Drive. Turn left on College Street. Turn right into the parking lot beside the Thistletown Multi-Service Centre at 925 Albion Road. STOP car and walk along laneway on the south side of the Thistletown Multi-Service Centre into the park at the rear.

Stop Seventeen (Map H): Village Green Park

Village Green Park is located behind the Thistletown Multi-Service Centre at 925 Albion Road. This park's origins go back to 1895 when William Grubb and James Farr applied to have an unused road allowance closed between their lots 31 and 32. However, in August 1895, Etobicoke Council received a petition from the residents of Thistletown objecting to the closing of the road allowance “unless a piece of land be given in lieu thereof for a park for the town.” On November 4, 1895, By-law No. 595 was passed by Etobicoke Council permitting the road allowance closure. On July 6, 1896, Council passed a motion to “execute a conveyance of that part of the road allowance between lots 31 and 32, Con. B, as described in plans and specifications prepared by George W. McFarlen, O.L.S., and dated July 3, 1896, to Jonathan Tabor Farr [James’ son, who now owned Lot 32], and accept the conveyance from him of 2 8/100 acres of Lot 32, Con. B ...”

In effect, Farr gave up 2.08 acres of land to obtain a parcel of about 6.25 acres. The 2.08 acre plot of land was to be held in trust for use as a public park for the people of the village of Thistletown and vicinity. This was the first public park in Etobicoke, and it has been used continuously since 1896 for community and school events, agricultural fairs, a skating rink and a sports’ field. A Village Green Festival has been held here every June since 1984.

The village’s first school was built facing Islington Avenue just south of Albion Road in 1874 and moved to the location of to-day’s Multi-Service Centre in 1901. In 1910, Thistletown Public Hall was built on the Village Green just west of the school and was used for exhibitions, public meetings and extra classroom space. The school was replaced in 1947 with the current building, and the public hall was demolished in 1972. Thistletown Public School was closed in 1985, and the building became the Thistletown Multi-Service Centre, owned by the Toronto District School Board but operated by the city as a community and seniors’ centre. In 2016, the TDSB decided to sell the Multi-Service Centre and the Village Green. Fearing the loss of the Multi-Service Centre and the Village Green to the community, local resident Joanna Twitchin produced the original “Village Green Act” as evidence that the Village Green belonged to the City, not the TDSB. The City bought the Multi-Service Centre, and is now the official Guardian/Trustee of Village Green Park, thus saving both entities for the use of the Thistletown community.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to College Street and turn left. Turn left at Riverdale Drive and turn right almost immediately at Albion Road. Turn left at the next street, Calstock Drive, and right almost immediately at Alhart Drive. Turn right at next street, Bankfield Drive. Continue until you see Anga’s Farm and Nursery on the left. STOP at the side of the road.

In effect, Farr gave up 2.08 acres of land to obtain a parcel of about 6.25 acres. The 2.08 acre plot of land was to be held in trust for use as a public park for the people of the village of Thistletown and vicinity. This was the first public park in Etobicoke, and it has been used continuously since 1896 for community and school events, agricultural fairs, a skating rink and a sports’ field. A Village Green Festival has been held here every June since 1984.

The village’s first school was built facing Islington Avenue just south of Albion Road in 1874 and moved to the location of to-day’s Multi-Service Centre in 1901. In 1910, Thistletown Public Hall was built on the Village Green just west of the school and was used for exhibitions, public meetings and extra classroom space. The school was replaced in 1947 with the current building, and the public hall was demolished in 1972. Thistletown Public School was closed in 1985, and the building became the Thistletown Multi-Service Centre, owned by the Toronto District School Board but operated by the city as a community and seniors’ centre. In 2016, the TDSB decided to sell the Multi-Service Centre and the Village Green. Fearing the loss of the Multi-Service Centre and the Village Green to the community, local resident Joanna Twitchin produced the original “Village Green Act” as evidence that the Village Green belonged to the City, not the TDSB. The City bought the Multi-Service Centre, and is now the official Guardian/Trustee of Village Green Park, thus saving both entities for the use of the Thistletown community.

DRIVING INSTRUCTIONS: Return to College Street and turn left. Turn left at Riverdale Drive and turn right almost immediately at Albion Road. Turn left at the next street, Calstock Drive, and right almost immediately at Alhart Drive. Turn right at next street, Bankfield Drive. Continue until you see Anga’s Farm and Nursery on the left. STOP at the side of the road.

Stop Eighteen (Map I): Anga’s Farm and Nursery, 89 Bankfield Drive

Anga’s Farm and Nursery is located on property once owned by John Grubb. It started as a 20 hectare lot, but over the years parts were sold and the present farm is only 1.4 hectares. It is the last privately-owned working farm in Toronto, and has survived to this day because the land was declared floodplain after Hurricane Hazel in 1954 and development was not allowed. The current owner, John Anga, operates a plant nursery and greenhouse, grows tree fruits and vegetables, and produces honey that he sells locally.